Reaction engine

Examples include jet engines, rocket engines, pump-jets, and more uncommon variations such as Hall effect thrusters, ion drives, mass drivers, and nuclear pulse propulsion.

The discovery of the reaction engine has been attributed to the Romanian inventor Alexandru Ciurcu and to the French journalist Just Buisson [fr; ro].

This comes to an exhaust velocity of about ⅔ of the mission delta-v (see the energy computed from the rocket equation).

Drives with a specific impulse that is both high and fixed such as Ion thrusters have exhaust velocities that can be enormously higher than this ideal, and thus end up powersource limited and give very low thrust.

When this is achieved, the exhaust stops in space [NB 1] and has no kinetic energy; and the propulsive efficiency is 100% all the energy ends up in the vehicle (in principle such a drive would be 100% efficient, in practice there would be thermal losses from within the drive system and residual heat in the exhaust).

Some drives (such as VASIMR or electrodeless plasma thruster) actually can significantly vary their exhaust velocity.

This can help reduce propellant usage and improve acceleration at different stages of the flight.

However the best energetic performance and acceleration is still obtained when the exhaust velocity is close to the vehicle speed.

Proposed ion and plasma drives usually have exhaust velocities enormously higher than that ideal (in the case of VASIMR the lowest quoted speed is around 15 km/s compared to a mission delta-v from high Earth orbit to Mars of about 4 km/s).

For a mission, for example, when launching from or landing on a planet, the effects of gravitational attraction and any atmospheric drag must be overcome by using fuel.

For example, rocket engines can be up to 60–70% energy efficient in terms of accelerating the propellant.

The rest is lost as heat and thermal radiation, primarily in the exhaust.

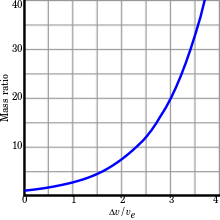

[NB 2] Exhausting the entire usable propellant of a spacecraft through the engines in a straight line in free space would produce a net velocity change to the vehicle; this number is termed delta-v (

much smaller than ve, this equation is roughly linear, and little reaction mass is needed.

For a mission, for example, when launching from or landing on a planet, the effects of gravitational attraction and any atmospheric drag must be overcome by using fuel.

Some effects such as Oberth effect can only be significantly utilised by high thrust engines such as rockets; i.e., engines that can produce a high g-force (thrust per unit mass, equal to delta-v per unit time).

If the reaction mass had to be accelerated from zero speed to the exhaust speed, all energy produced would go into the reaction mass and nothing would be left for kinetic energy gain by the rocket and payload.

However, if the rocket already moves and accelerates (the reaction mass is expelled in the direction opposite to the direction in which the rocket moves) less kinetic energy is added to the reaction mass.

The remaining 30 MJ is the increase of the kinetic energy of the rocket and payload.

In the case of using the rocket for deceleration; i.e., expelling reaction mass in the direction of the velocity,

The latter causes a reduction of thrust, so it is a disadvantage even when the objective is to lose energy (deceleration).

The actual fuel value is higher, but much of the energy is lost as waste heat in the exhaust that the nozzle was unable to extract.

This can be the case when the reaction mass has a lower speed after being expelled than before – rockets are able to liberate some or all of the initial kinetic energy of the propellant.

For example, a launch to Low Earth orbit (LEO) normally requires a

To do this with the ion or more theoretical electrical drives, the engine would have to be supplied with one to several gigawatts of power, equivalent to a major metropolitan generating station.

Alternative approaches include some forms of laser propulsion, where the reaction mass does not provide the energy required to accelerate it, with the energy instead being provided from an external laser or other beam-powered propulsion system.

This lower power is only sufficient to accelerate a tiny amount of fuel per second, and would be insufficient for launching from Earth.

However, over long periods in orbit where there is no friction, the velocity will be finally achieved.

For example, it took the SMART-1 more than a year to reach the Moon, whereas with a chemical rocket it takes a few days.

Mission planning therefore frequently involves adjusting and choosing the propulsion system so as to minimise the total cost of the project, and can involve trading off launch costs and mission duration against payload fraction.