Delta-v

and pronounced /dɛltə viː/, as used in spacecraft flight dynamics, is a measure of the impulse per unit of spacecraft mass that is needed to perform a maneuver such as launching from or landing on a planet or moon, or an in-space orbital maneuver.

A simple example might be the case of a conventional rocket-propelled spacecraft, which achieves thrust by burning fuel.

It is used to determine the mass of propellant required for the given maneuver through the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation.

However, this relation does not hold in the general case: if, for instance, a constant, unidirectional acceleration is reversed after (t1 − t0)/2 then the velocity difference is 0, but delta-v is the same as for the non-reversed thrust.

In addition, the costs for atmospheric losses and gravity drag are added into the delta-v budget when dealing with launches from a planetary surface.

[1] Orbit maneuvers are made by firing a thruster to produce a reaction force acting on the spacecraft.

of the spacecraft caused by this force will be where m is the mass of the spacecraft During the burn the mass of the spacecraft will decrease due to use of fuel, the time derivative of the mass being If now the direction of the force, i.e. the direction of the nozzle, is fixed during the burn one gets the velocity increase from the thruster force of a burn starting at time

and ending at t1 as Changing the integration variable from time t to the spacecraft mass m one gets Assuming

to be a constant not depending on the amount of fuel left this relation is integrated to which is the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation.

If for example 20% of the launch mass is fuel giving a constant

of 2100 m/s (a typical value for a hydrazine thruster) the capacity of the reaction control system is

Like this one can for example use a "patched conics" approach modeling the maneuver as a shift from one Kepler orbit to another by an instantaneous change of the velocity vector.

This approximation with impulsive maneuvers is in most cases very accurate, at least when chemical propulsion is used.

But even for geostationary spacecraft using electrical propulsion for out-of-plane control with thruster burn periods extending over several hours around the nodes this approximation is fair.

The time-rate of change of delta-v is the magnitude of the acceleration caused by the engines, i.e., the thrust per total vehicle mass.

The total delta-v needed is a good starting point for early design decisions since consideration of the added complexities are deferred to later times in the design process.

Therefore, in modern spacecraft propulsion systems considerable study is put into reducing the total delta-v needed for a given spaceflight, as well as designing spacecraft that are capable of producing larger delta-v. Increasing the delta-v provided by a propulsion system can be achieved by: Because the mass ratios apply to any given burn, when multiple maneuvers are performed in sequence, the mass ratios multiply.

Thus delta-v is commonly quoted rather than mass ratios which would require multiplication.

When designing a trajectory, delta-v budget is used as a good indicator of how much propellant will be required.

Propellant usage is an exponential function of delta-v in accordance with the rocket equation, it will also depend on the exhaust velocity.

When rocket thrust is applied in short bursts the other sources of acceleration may be negligible, and the magnitude of the velocity change of one burst may be simply approximated by the delta-v.

The total delta-v to be applied can then simply be found by addition of each of the delta-v's needed at the discrete burns, even though between bursts the magnitude and direction of the velocity changes due to gravity, e.g. in an elliptic orbit.

For examples of calculating delta-v, see Hohmann transfer orbit, gravitational slingshot, and Interplanetary Transport Network.

From power considerations, it turns out that when applying delta-v in the direction of the velocity the specific orbital energy gained per unit delta-v is equal to the instantaneous speed.

For example, a satellite in an elliptical orbit is boosted more efficiently at high speed (that is, small altitude) than at low speed (that is, high altitude).

Another example is that when a vehicle is making a pass of a planet, burning the propellant at closest approach rather than further out gives significantly higher final speed, and this is even more so when the planet is a large one with a deep gravity field, such as Jupiter.

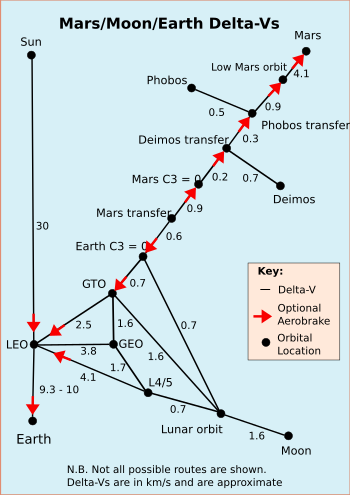

[4] Delta-v needed for various orbital manoeuvers using conventional rockets; red arrows show where optional aerobraking can be performed in that particular direction, black numbers give delta-v in km/s that apply in either direction.

[5][6] Lower-delta-v transfers than shown can often be achieved, but involve rare transfer windows or take significantly longer, see: Orbital mechanics § Interplanetary Transport Network and fuzzy orbits.

For example the Soyuz spacecraft makes a de-orbit from the ISS in two steps.

First, it needs a delta-v of 2.18 m/s for a safe separation from the space station.