Real wages

Specifically, inflation could be calculated based on any good or service or combination thereof, and real wage has still increased.

This of course leaves many scenarios where real wage increasing, decreasing or staying the same depends upon how inflation is calculated.

To have an accurate view of a nation's wealth in any given year, inflation has to be taken into account and real wages must be used as one measuring stick.

There are further limitations in the traditional measures of wages, such as failure to incorporate additional employment benefits, or not adjusting for a changing composition of the overall workforce.

[1] An alternative is to look at how much time it took to earn enough money to buy various items in the past, which is one version of the definition of real wages as the amount of goods or services that can be bought.

Such an analysis shows that for most items, it takes much less work time to earn them now than it did decades ago, at least in the United States.

The nominal wage increases a worker sees in his paycheck may give a misleading impression of whether he is "getting ahead" or "falling behind" over time.

In this phase, population growth has been more restrained, and as such real wages have risen much more dramatically with rapid increases in technology and productivity over time.

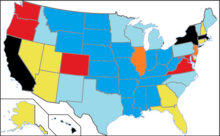

[12] The countries of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom have experienced strong real wage growth following European integration in the early 1980s.

[a] It studied the OECD with a focus on the UK, finding that unemployment rates often returned to 2007's pre-great recession levels.

So it argues that the low unemployment rates hide continued "labour market slack": its models found underemployment was negatively related to wages both in the UK and other countries.