Recognition memory

[2] As first established by psychology experiments in the 1970s, recognition memory for pictures is quite remarkable: humans can remember thousands of images at high accuracy after seeing each only once and only for a few seconds.

Arthur Allin (1896) was the first person to publish an article attempting to explicitly define and differentiate between subjective and objective definitions of the experience of recognition although his findings are based mostly on introspections.

[6] Woodsworth (1913) and Margaret and Edward Strong (1916) were the first people to experimentally use and record findings employing the delayed matching to sample task to analyze recognition memory.

[9] In 1980 George Mandler introduced the recollection-familiarity distinction, more formally known as the dual process theory[4] It is debatable whether familiarity and recollection should be considered as separate categories of recognition memory.

"[10] A common criticism of dual process models of recognition is that recollection is simply a stronger (i.e. more detailed or vivid) version of familiarity.

Further, eye tracking evidence revealed that participants looked longer at the correct stimulus, and this was related to increases in hippocampal activity.

Therefore, the hippocampus may play a role in the recovery of relational information, but it requires concomitant activation with the prefrontal cortex for conscious recollection.

A number of reports feature patients with selective damage to the hippocampus who are impaired only in recollection but not in familiarity, which provides tentative support for dual-process models.

She exhibited impaired familiarity but intact recollection processes relative to controls in a yes-no recognition paradigm, and this was elucidated using ROC, RK, and response-deadline procedures.

[16] While performance was matched post hoc and replication is needed, this evidence rules out the idea that these brain regions are part of a unitary memory strength system.

[1] The question of whether recollection and familiarity exist as two independent categories or along a continuum may ultimately be irrelevant; the bottom line is that the recollection-familiarity distinction has been extremely useful in understanding how recognition memory works.

[25] Signal detection theory has been applied to recognition memory as a method of estimating the effect of the application of these internal criteria, referred to as bias.

[42] For example, if the original list contained "blackbird, jailbait, buckwheat", a feature error may be elicited through the presentation of "buckshot" or "blackmail" at test, as each of these lures has an old and a new component.

On the whole, research concerning the neural substrates of familiarity and recollection demonstrates that these processes typically involve different brain regions, thereby supporting a dual-process theory of recognition memory.

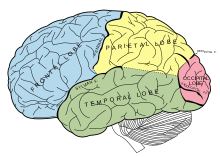

[49] The hippocampus plays a prominent role in recollection whereas familiarity depends heavily on the surrounding medial-temporal regions, especially the perirhinal cortex.

Perhaps misleadingly, the regions of the brain listed above correspond to an abstract and highly generalized understanding of recognition memory, in which the stimuli or items-to-be-recognized are not specified.

Several studies have shown that when an individual is devoting his/her full attention to the memorization process, the strength of the successful memory is related to the magnitude of bilateral activation in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and parahippocampal gyrus.

Recognition memory is not confined to the visual domain; we can recognize things in each of the five traditional sensory modalities (i.e. sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste).

Although most neuroscientific research has focused on visual recognition, there have also been studies related to audition (hearing), olfaction (smell), gustation (taste), and tactition (touch).

Auditory recognition memory is primarily dependent on the medial temporal lobe as displayed by studies on lesioned patients and amnesics.

[60] Moreover, studies conducted on monkeys[61] and dogs[62] have confirmed that perinhinal and entorhinal cortex lesions fail to affect auditory recognition memory as they do in vision.

[63] Research on human olfaction is scant in comparison to other senses such as vision and hearing, and studies specifically devoted to olfactory recognition are even rarer.

[73] Lesions to various brain regions such as these serve as case study data that help researchers understand the neural correlates of recognition.

It has been well documented that damage here can result in severe retrograde or anterograde amnesia, the patient is unable to recollect certain events from their past or create new memories respectively.

More recent neuroimaging research has begun to demonstrate that the parietal lobe plays an important, though often subtle[81] role in recognition memory as well.

[81] Qualitative content in memories helps to distinguish those recollected, so impairment of this function reduces confidence in recognition judgments, as in parietal lobe lesion patients.

The mnemonic-accumulator hypothesis postulates that the parietal lobe holds a memory strength signal, which is compared with internal criteria to make old/new recognition judgments.

[88] Patients with frontal lobe lesions also showed evidence of marked anterograde and relatively mild retrograde face memory impairment.

The speed and accuracy of an old/new recognition judgment are two components in a series of cognitive processes that allow humans to identify and respond to potential dangers in their environments.

If people rely on recognition for use on a memory test (such as multiple choice) they may recognize one of the options but this does not necessarily mean it is the correct answer.