24-cell

The vertex figure of a 16-cell is the octahedron; thus, cutting the vertices of the 16-cell at the midpoint of its incident edges produces 8 octahedral cells.

[l] Hyper-tetrahedron 5-point Hyper-octahedron 8-point Hyper-cube 16-point 24-point Hyper-icosahedron 120-point Hyper-dodecahedron 600-point The 24 vertices and 96 edges form 16 non-orthogonal great hexagons,[o] four of which intersect[i] at each vertex.

[af] The √1 edges occur in 16 hexagonal great circles (in planes inclined at 60 degrees to each other), 4 of which cross[q] at each vertex.

[ai] The √2 chords occur in 18 square great circles (3 sets of 6 orthogonal planes[x]), 3 of which cross at each vertex.

[aj] The 72 distinct √2 chords do not run in the same planes as the hexagonal great circles; they do not follow the 24-cell's edges, they pass through its octagonal cell centers.

[aw] Great circles which are completely orthogonal or otherwise Clifford parallel[ad] do not intersect at all: they pass through disjoint sets of vertices.

[ax] Triangles and squares come together uniquely in the 24-cell to generate, as interior features,[ay] all of the triangle-faced and square-faced regular convex polytopes in the first four dimensions (with caveats for the 5-cell and the 600-cell).

[t] They overlap with each other, but most of their element sets are disjoint: they share some vertex count, but no edge length, face area, or cell volume.

[bi] The 24-cell can be constructed directly from its characteristic simplex , the irregular 5-cell which is the fundamental region of its symmetry group F4, by reflection of that 4-orthoscheme in its own cells (which are 3-orthoschemes).

The 16-cells are inscribed in the 24-cell[bl] such that only their vertices are exterior elements of the 24-cell: their edges, triangular faces, and tetrahedral cells lie inside the 24-cell.

When interpreted as the quaternions,[k] the F4 root lattice (which is the integral span of the vertices of the 24-cell) is closed under multiplication and is therefore a ring.

The unit balls inscribed in the 24-cells of this tessellation give rise to the densest known lattice packing of hyperspheres in 4 dimensions.

[c] The regular convex 4-polytopes are an expression of their underlying symmetry which is known as SO(4), the group of rotations[43] about a fixed point in 4-dimensional Euclidean space.

It takes a 720 degree isoclinic rotation for each hexagram2 geodesic to complete a circuit through every second vertex of its six vertices by winding around the 24-cell twice, returning the 24-cell to its original chiral orientation.

The different convex regular 4-polytopes nest inside each other, and multiple instances of the same 4-polytope hide next to each other in the Clifford parallel spaces that comprise the 3-sphere.

Six regular octahedra can be connected face-to-face along a common axis that passes through their centers of volume, forming a stack or column with only triangular faces.

Four Clifford parallel great hexagons comprise a discrete fiber bundle covering all 24 vertices in a Hopf fibration.

[61] Each fibration is the domain (container) of a unique left-right pair of isoclinic rotations (left and right Hopf fiber bundles).

The hexagram does not lie in a single central plane, but is composed of six linked √3 chords from the six different hexagon great circles in the 6-cell ring.

[cj] Rather than a flat hexagon, it forms a skew hexagram out of two three-sided 360 degree half-loops: open triangles joined end-to-end to each other in a six-sided Möbius loop.

[cu] Each 6-cell ring contains six such hexagram isoclines, three black and three white, that connect even and odd vertices respectively.

[ce] When it has traversed one chord from each of the six great hexagons, after 720 degrees of isoclinic rotation (either left or right), it closes its skew hexagram and begins to repeat itself, circling again through the black (or white) vertices and cells.

At that vertex the octagram makes two right-angled turns at once: 90° around the great square, and 90° orthogonally into a different 4-cell ring entirely.

[bj] The characteristic 5-cell of the regular 24-cell is represented by the Coxeter-Dynkin diagram , which can be read as a list of the dihedral angles between its mirror facets.

around its exterior right-triangle face (the edges opposite the characteristic angles 𝟀, 𝝉, 𝟁),[ec] plus

For visualization purposes, it is convenient that the octahedron has opposing parallel faces (a trait it shares with the cells of the tesseract and the 120-cell).

The 24-cell is the only regular polytope in more than two dimensions where you can traverse a great circle purely through opposing vertices (and the interior) of each cell.

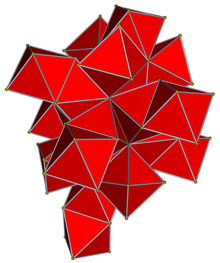

Twelve of the 24 octahedral cells project in pairs onto six square dipyramids that meet at the center of the rhombic dodecahedron.

Two of the octahedral cells, the nearest and farther from the viewer along the w-axis, project onto an octahedron whose vertices lie at the center of the cuboctahedron's square faces.

This corresponds with the decomposition of the cuboctahedron into a regular octahedron and 8 irregular but equal octahedra, each of which is in the shape of the convex hull of a cube with two opposite vertices removed.