Victorian dress reform

Dress reformers were also influential in persuading women to adopt simplified garments for athletic activities such as bicycling or swimming.

The movement was much less concerned with men's clothing, although it initiated the widespread adoption of knitted wool union suits or long johns.

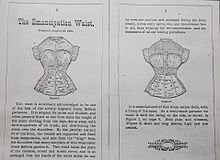

[5] Doctors such as Alice Bunker Stockham counseled patients against them, particularly during maternity; reformist and activist Catharine Beecher was one of the few to defy propriety norms and discuss the gynecological issues resulting from lifelong corset usage, in particular uterine prolapse.

[6][7] Feminist historian Leigh Summers theorized that some moral panic derived from the common but unspeakable idea that tightlacing could be used to induce an abortion.

[9] While supporters of fashionable dress contended that corsets maintained an upright, 'good figure', as a necessary physical structure for moral and well-ordered society, these dress reformists contested that women's fashions were not only physically detrimental, but "the results of male conspiracy to make women subservient by cultivating them in slave psychology.

In 1878, a German professor named Gustav Jaeger published a book claiming that only clothing made of animal hair, such as wool, promoted health.

A British accountant named Lewis Tomalin translated the book, then opened a shop selling Dr Jaeger's Sanitary Woollen System, including knitted wool union suits.

In 1851, a New England temperance activist named Elizabeth Smith Miller (Libby Miller) adopted what she considered a more rational costume: loose trousers gathered at the ankles, like the trousers worn by Middle Eastern and Central Asian women, topped by a short dress or skirt and vest (waistcoat).

In the 1870s, a largely English movement led by Mary Eliza Haweis sought dress reform to enhance and celebrate the natural shape of the body, preferring the looser lines of the medieval and renaissance eras.

[19] The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and other artistic reformers objected to the elaborately trimmed confections of Victorian fashion with their unnatural silhouette based on a rigid corset and hoops as both ugly and dishonest.

Some women associated with the movement adopted a revival style based on romanticised medieval influences such as puffed juliette sleeves and trailing skirts.

The dress reform movement spread from the United States and Great Britain to the Nordic countries in the 1880s and from Germany to Austria and the Netherlands.

[23][page needed] Gustav Klimt and Emilie Flöge are said to have cooperated in designing reform fashion, and such clothing was associated with the Wiener Werkstätte.

[21] In the early 20th century, however, the French fashion industry was finally influenced by the reform dress movement, which abolished the corset by the 1910s.

Two weeks later the German dress reform association, Allgemeiner Verein zur Verbesserung der Frauenkleidung, was founded.

[21] The dress reform society held lectures, participated in exhibitions and worked with designed to produce a new fashion for women which could be not only attractive but also comfortable and healthy at the same time.

Johanne Biörn held lectures in the Oslo schools, and the Norwegian designer Kristine Dahl experienced success not only in her home country of Norway but also in Sweden, becoming a central figure of the dress reform movement.

[25] After a speech by Anne Charlotte Leffler held at the women's club Nya Idun, the Friends of Handicraft gave Hanna Winge the assignment to design a reform costume, which was produced by Augusta Lundin and exhibited in public, which gave further publicity to the issue, and in 1886, the Swedish Dress Reform Society was founded.

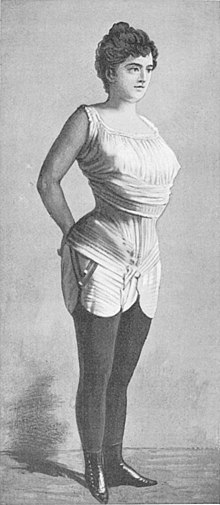

[31] Embodying the New Woman idea, women donned masculine-inspired fashions including simple tailored skirt suits, ties, and starched blouses.

"[34] Although forms of corsets, girdles and bras were worn well into the 1960s, as Riegel states, "Feminine emancipation had brought greater dress reform than the most visionary of the early feminists had advocated.

Jessie: "Why, to wear, of course."

Gertrude: "But you haven't got a Bicycle!"

Jessie: "No; but I've got a Sewing Machine!"