Mali Empire

At that time, the Venetian explorer Alvise Cadamosto and Portuguese traders confirmed that the peoples who settled within Gambia River were still subject to the mansa of Mali.

[27] Sundiata Keita, born during the rise of Kaniaga, was the son of Niani's faama, Nare Fa (also known as Maghan Kon Fatta, meaning the handsome prince).

[4] During his reign, Sundiata's generals continued to expand the empire's frontiers, reaching from Kaabu in the west, Takrur, Oualata and Audaghost in the north, and the Soninke Wangara goldfields in the south.

[42] A devout and well-educated Muslim, he took an interest in the scholarly city of Timbuktu, which he peaceably annexed in 1324, and transformed Sankore from an informal madrasah into an Islamic university.

All of them agree that he took a very large group of people; the mansa kept a personal guard of some 500 men,[43] and he gave out so many alms and bought so many things that the value of gold in Egypt and Arabia depreciated for twelve years.

[47] Still, by the time of Mansa Musa Keita II's death in 1387, Mali was financially solvent and in control of all of its previous conquests except Gao and Dyolof.

Forty years after the reign of Mansa Musa Keita I, the Mali Empire still controlled some 1,100,000 square kilometres (420,000 sq mi) of land.

While maintaining a firm grip in the south and west, and even expanding in some areas, imperial control of their northernmost provinces was slipping, as attested by the Mossi raids on Macina.

[50][better source needed] In an attempt to stem the tide, Mansa Mahmud Keita II opened diplomatic relations with Portugal, receiving the envoys Pêro d'Évora and Gonçalo Enes in 1487.

[51] Songhai forces under the command of Askia Muhammad I defeated the Mali general Fati Quali Keita in 1502 and seized the province of Diafunu.

The Songhai Empire had fallen to the Saadi Sultanate of Morocco eight years earlier, and Mahmud sought to take advantage of their defeat by trying to capture Jenne.

The Kouroukan Fouga put in place social and economic reforms including prohibitions on the maltreatment of prisoners and slaves, installing documents between clans which clearly stated who could say what about whom.

Al-Umari, who wrote down a description of Mali based on information given to him by Abu Sa’id 'Otman ed Dukkali (who had lived 35 years in the capital), reported the realm as being square and an eight-month journey from its coast at Tura (at the mouth of the Senegal River) to Muli.

He describes it as being north of Mali but under its domination implying some sort of vassalage for the Antasar, Yantar'ras, Medussa and Lemtuna Berber tribes, with garrisons kept at Oualata, Timbuktu, Koumbi, and Gao, and responsibility of governing the Sahara given to the military commander (sura farin).

[85] Seemingly contradictory reports written by Arab visitors, a lack of definitive archaeological evidence, and the diversity of oral traditions all contribute to this uncertainty.

[86] A particular challenge lies in interpreting early Arabic manuscripts, in which, without vowel markings and diacritics, foreign names can be read in numerous different ways (e.g. Biti, Buti, Yiti, Tati).

"[87] Early European writers such as Maurice Delafosse believed that Niani, a city on what is now the border between Guinea and Mali, was the capital for most of the empire's history, and this notion has taken hold in the popular imagination.

The identification of Niani as imperial capital is rooted in an (possibly erroneous) interpretation of the Arab traveler al Umari's work, as well as some oral histories.

Extensive archaeological digs have shown that the area was an important trade and manufacturing center in the 15th century, but no firm evidence of royal residence has come to light.

A city called Dieriba or Dioliba is sometimes mentioned as the capital or main urban center of the province of Mande in the years before Sundiata, that was later abandoned.

[91] Kangaba became the last refuge of the Keita royal family after the collapse of the Mali Empire, and so has for centuries been associated with Sundiata in the cultural imagination of Mande peoples.

[92] According to Jules Vidal and Levtzion, citing oral histories from Kangaba and Keyla, another onetime capital was Manikoro or Mali-Kura, founded after the destruction of Niani.

[93] Parallel to this debate, many scholars have argued that the Mali Empire may not have had a permanent "capital" in the sense that the word is used today, and historically was used in the Mediterranean world.

[97] Written sources have Mansa Musa using a similar banner, 'with yellow symbols (shi’ār) on a red background', during his visit to Cairo, as well as a parasol.

The material of which they were made indicated the rank of the holder: gold was the highest, and reserved for the Mansa, followed in descending order by silver, brass, iron, and wood.

In the north weaving flourished, owing to cotton fields in regions such as Casamance, and the Soninke and Takrur peoples specially dyed their cloths indigo.

On the return from Takedda to Morocco, his caravan transported 600 female slaves, suggesting that slavery was a substantial part of the commercial activity of the empire.

As a result of steady tax revenue and stable government beginning in the last quarter of the 13th century, the Mali Empire was able to project its power throughout its own extensive domain and beyond.

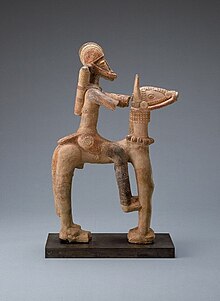

Free warriors from the north (Mandekalu or otherwise) were usually equipped with large reed or animal hide shields and a stabbing spear that was called a tamba.

[116] The earliest document mentioning the old Djenne mosque is Abd al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan, which gives the early history, presumably from the oral tradition as it existed in the mid seventeenth century.