Rensselaerswyck

Rensselaerswyck[a] was a Dutch colonial patroonship and later an English manor owned by the van Rensselaer family located in the present-day Capital District of New York in the United States.

At the time of his death in 1839, Steven van Rensselaer III's land holdings made him the tenth-richest American in history.

Under financial, judicial, and political pressure from this anti-rent movement, Stephen IV and William van Rensselaer sold off most of their land, ending the patroonship in the 1840s.

In the name of the States-General, it had the authority to make contracts and alliances with princes and natives, build forts, administer justice, appoint and discharge governors, soldiers, and public officers, and promote trade in New Netherland.

[4] To meet such cases, the West India Company adopted the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions for the agricultural colonization of its American province.

[7] Kiliaen van Rensselaer, a pearl and diamond merchant of Amsterdam, was one of the original directors of the Dutch West India Company[8] and one of the first to take advantage of the new settlement charter.

[9] On April 8, 1630, a representative for van Rensselaer purchased a large tract of land from its American Indian owners adjacent to Fort Orange, on the west side of the Hudson River.

The following is the oath stated by each tenant: I,

This territory was called "Semesseck" by the Indians, and described in the grant as "lying on the east side of the aforesaid river, opposite the Fort Orange, as well above as below, and from Poetanock, the millcreek, northward to Negagonee, being about twelve miles, large measure.

[11] The government of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck was vested in a general court, which exercised executive, legislative or municipal, and judicial functions.

[4] The population of the colony of Rensselaerswyck in its early days consisted of three classes: freemen on top, who emigrated from Holland at their own expense; farmers next; and farm servants sent by the patroon at the bottom of the caste system.

The Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts, a collection of translated primary documents from that time, state, The present letters show beyond the possibility of doubt that Kiliaen van Rensselaer did not visit his colony in person between 1630 and 1643, and the records preserved among the Rensselaerswyck manuscripts make it equally certain that he did not do so between the last named date and his death…[16][17][18][19] some say 1645,[20]The estate was inherited by his eldest son Jan Baptist, who acquired the title of patroon.

[22] Jeremias died in 1674 and the estate was passed on to his oldest son, Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, grandson to the first patroon, his namesake.

[29] During Kiliaen's tenure as patroon, he served in many political appointed positions in Albany, including assessor, justice, and supervisor, and represented Rensselaerswyck in the New York General Assembly.

[28] Hendrick van Rensselaer lived in Albany until a year after receiving the Lower Manor, representing Rensselaerswyck in the General Assembly[b] from 1705 until 1715,[30] just as his brother had from 1693 to 1704.

One of his land deals was made in the eastern region of Rensselaerswyck; the Town of Stephentown in southeastern Rensselaer County was named for him.

[32] The Manor passed on to his eldest son Stephen van Rensselaer III, who was five at the time of his father's death.

He was also commissioned a lieutenant general in the New York State Militia, and led an unsuccessful invasion of Canada at Niagara in the War of 1812.

[33] At the time of his death, Stephen III was worth about $10 million (about $88 billion in 2007 dollars) and is noted as being the tenth-richest American in history.

[1] The spectacle of a landed gentleman living in semi-feudal splendor among his 3,000 tenants was an anachronism to a postwar generation that had become acclimated to Jacksonian democracy.

Stephen IV, who had inherited the "West Manor" (Albany County), refused to meet with a committee of anti-renters and turned down their written request for a reduction of rents.

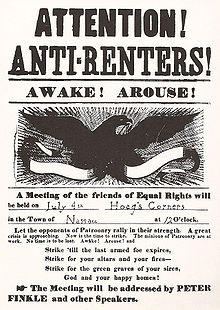

On July 4, 1839, a mass meeting at Berne called for a declaration of independence from landlord rule but raised the amount the tenants were willing to pay.

Crowds of angry tenants manhandled Sheriff Michael Archer and his assistants and turned back a posse of 500 men.

Seward's proclamation calling on the people not to resist the enforcement of the law and the presence of several hundred militiamen failed to cow the tenants, who persisted in their refusal to pay rent.

[34] By 1844, the anti-rent movement had grown from a localized struggle against the van Rensselaer family to a full-fledged revolt against leasehold tenure throughout eastern New York, where other major manors existed.

In late 1844, Governor William Bouck sent three companies of militia to Hudson, where anti-renters threatened to storm the jail and release their leader, Big Thunder (Smith A. Boughton, in private life).

The following year Governor Silas Wright was forced to declare Delaware County in a state of insurrection after an armed rider had killed undersheriff Osman N. Steele August 7, 1845 at an eviction sale.

Shortly thereafter, the Constitutional Convention of 1846 prohibited any future lease of agricultural land which claimed rent or service for a period longer than twelve years.

As a result, they had a small but determined bloc of anti-rent champions in the Assembly and the Senate who kept landlords uneasy by threatening to pass laws challenging land titles.

[34] Assailed by a concerted conspiracy not to pay rent and harassed by taxes and investigations of the Attorney General, the landed proprietors gradually sold out their interests.