Spolia

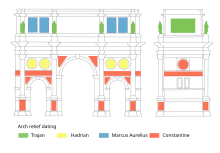

[1] Roman examples include the Arch of Janus, the earlier imperial reliefs reused on the Arch of Constantine, the colonnade of Old Saint Peter's Basilica; examples in Byzantine territories include the exterior sculpture on the Panagia Gorgoepikoos church in Athens); in the medieval West Roman tiles were reused in St Albans Cathedral, in much of the medieval architecture of Colchester, porphyry columns in the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, and the colonnade of the basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere.

Although the modern literature on spolia is primarily concerned with these and other medieval examples, the practice is common and there is probably no period of art history in which evidence for "spoliation" could not be found.

Ideological readings might describe the re-use of art and architectural elements from former empires or dynasties as triumphant (that is, literally as the display of "spoils" or "booty" of the conquered) or as revivalist (proclaiming the renovation of past imperial glories).

Liz James extends Foss's observation[3] in noting that statues, laid on their sides and facing outwards, were carefully incorporated in Ankara's city walls in the 7th century, at a time when spolia were also being built into city walls in Miletus, Sardis, Ephesus and Pergamum: "laying a statue on its side places it and the power it represents under control.

[4] There has been considerable controversy over the use of Jewish gravestones as pavement materials in several Eastern European countries during and after The Holocaust,[5][6][7] as well as by Jordan during their rule over East Jerusalem.