Resistor

In electronic circuits, resistors are used to reduce current flow, adjust signal levels, to divide voltages, bias active elements, and terminate transmission lines, among other uses.

Variable resistors can be used to adjust circuit elements (such as a volume control or a lamp dimmer), or as sensing devices for heat, light, humidity, force, or chemical activity.

For example, 8K2 as part marking code, in a circuit diagram or in a bill of materials (BOM) indicates a resistor value of 8.2 kΩ.

Excessive power dissipation may raise the temperature of the resistor to a point where it can burn the circuit board or adjacent components, or even cause a fire.

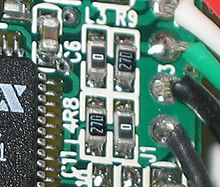

[9] A family of discrete resistors may also be characterized according to its form factor, that is, the size of the device and the position of its leads (or terminals).

Through-hole components typically have "leads" (pronounced /liːdz/) leaving the body "axially", that is, on a line parallel with the part's longest axis.

Other components may be SMT (surface mount technology), while high power resistors may have one of their leads designed into the heat sink.

Early 20th-century carbon composition resistors had uninsulated bodies; the lead wires were wrapped around the ends of the resistance element rod and soldered.

Carbon composition resistors were commonly used in the 1960s and earlier, but are not popular for general use now as other types have better specifications, such as tolerance, voltage dependence, and stress.

Moreover, if internal moisture content, such as from exposure for some length of time to a humid environment, is significant, soldering heat creates a non-reversible change in resistance value.

A carbon pile resistor can also be used as a speed control for small motors in household appliances (sewing machines, hand-held mixers) with ratings up to a few hundred watts.

[17] Thick film resistors may use the same conductive ceramics, but they are mixed with sintered (powdered) glass and a carrier liquid so that the composite can be screen-printed.

Wirewound resistors are commonly made by winding a metal wire, usually nichrome, around a ceramic, plastic, or fiberglass core.

One range of ultra-precision foil resistors offers a TCR of 0.14 ppm/°C, tolerance ±0.005%, long-term stability (1 year) 25 ppm, (3 years) 50 ppm (further improved 5-fold by hermetic sealing), stability under load (2000 hours) 0.03%, thermal EMF 0.1 μV/°C, noise −42 dB, voltage coefficient 0.1 ppm/V, inductance 0.08 μH, capacitance 0.5 pF.

[citation needed] An ammeter shunt is a special type of current-sensing resistor, having four terminals and a value in milliohms or even micro-ohms.

In heavy-duty industrial high-current applications, a grid resistor is a large convection-cooled lattice of stamped metal alloy strips connected in rows between two electrodes.

Such industrial grade resistors can be as large as a refrigerator; some designs can handle over 500 amperes of current, with a range of resistances extending lower than 0.04 ohms.

A potentiometer (colloquially, pot) is a three-terminal resistor with a continuously adjustable tapping point controlled by rotation of a shaft or knob or by a linear slider.

[23] The name potentiometer comes from its function as an adjustable voltage divider to provide a variable potential at the terminal connected to the tapping point.

A typical low power potentiometer (see drawing) is constructed of a flat resistance element (B) of carbon composition, metal film, or conductive plastic, with a springy phosphor bronze wiper contact (C) which moves along the surface.

Electronic analog computers used them in quantity for setting coefficients and delayed-sweep oscilloscopes of recent decades included one on their panels.

All types offer a convenient way of selecting and quickly changing a resistance in laboratory, experimental and development work without needing to attach resistors one by one, or even stock each value.

Some laboratory quality ohmmeters, milliohmmeters, and even some of the better digital multimeters sense using four input terminals for this purpose, which may be used with special test leads called Kelvin clips.

[27] Since 1990 the international resistance standard has been based on the quantized Hall effect discovered by Klaus von Klitzing, for which he won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1985.

[30] Early power wirewound resistors, such as brown vitreous-enameled types, were made with a system of preferred values like some of those mentioned here.

This process of sorting parts based on post-production measurement is known as "binning", and can be applied to other components than resistors (such as speed grades for CPUs).

While not an example of "noise" per se, a resistor may act as a thermocouple, producing a small DC voltage differential across it due to the thermoelectric effect if its ends are at different temperatures.

In applications where the thermoelectric effect may become important, care has to be taken to mount the resistors horizontally to avoid temperature gradients and to mind the air flow over the board.

[40] The failure rate of resistors in a properly designed circuit is low compared to other electronic components such as semiconductors and electrolytic capacitors.

This may be due to dirt or corrosion and is typically perceived as "crackling" as the contact resistance fluctuates; this is especially noticed as the device is adjusted.

- common

- bifilar

- common on a thin former

- Ayrton–Perry