Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering

[1][2] In the last two decades RIXS has been widely exploited to study the electronic, magnetic and structural properties of quantum materials and molecules.

[1][2][3] Due to the intrinsic inefficiency of the RIXS process, extremely brilliant sources of X-rays are crucial.

In addition to that, the possibility to tune the energy of the incoming X-rays is compelling to match a chosen resonance.

[1][2] Exploiting different experimental setups, RIXS can be performed using both soft and hard X-rays, spanning a vast range of absorption edges and thus samples to be studied.

Since the probability of a radiative core hole relaxation is low, the RIXS cross section is very small and a high brilliance X-ray source is needed.

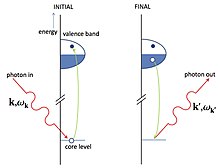

[1][5] In direct RIXS, the incoming photon promotes a core-electron to an empty valence band state.

If the hole is in the filled valence shell, the electron-hole excitation can propagate through the material, carrying away momentum and energy.

[5][10][11] In general the natural linewidth of a spectral feature is determined by the life-times of initial and final states.

Since RIXS exploits high energy photons in the X-ray range, a very large combined resolving power (103-105 depending on the goal of the experiment) is needed to detail the different spectral features.

[13] State of the art soft X-rays RIXS beamlines in use at the ESRF, at DLS and at NSLS II, have reached approximately 40000 of combined resolving power, leading to a record energy resolution of 25 meV at Cu L3 edge.

[13][14][15][16][19] The whole optical path from the source to the CCD must be kept in UHV to minimize the absorption of X-rays by air.

In addition to that, a non-negligible contribution to the combined resolving power is due to the imperfections on the surface of mirrors and gratings (slope error).

[13][14][15][16] After the collecting optics X-rays are dispersed by the varied line spacing (VLS) grating that can be either plane or spherical.

[13][14][15][16] Since the spectral analysis of the scattered X-rays is done through a dispersive grating, longer spectrometers offer higher resolving power.

This means that the source (X-rays spot on the sample), the analyzers and the detector must sit on the Rowland circle.

The resonance greatly enhances the valence contribution to the inelastic scattering cross section, sometimes by many orders of magnitude.

[3][2][1][26] Comparing the energy of a neutron, electron or photon with a wavelength of the order of the relevant length scale in a solid - as given by the de Broglie equation considering the interatomic lattice spacing is in the order of Ångströms - it derives from the relativistic energy–momentum relation that an X-ray photon has more energy than a neutron or electron.

In particular, high-energy X-rays carry a momentum that is comparable to the inverse lattice spacing of typical condensed matter systems so that, unlike Raman scattering experiments with visible or infrared light, RIXS can probe the full dispersion of low energy excitations in solids.

RIXS can even differentiate between the same chemical element at sites with different valencies or at inequivalent crystallographic positions as long as the X-ray absorption edges in these cases are distinguishable.

This constraint arises from the fact that in RIXS the scattered photons do not add or remove charge from the sample.

[1][31][32][33] Electron-hole continuum and excitons in band metals, doped systems and semiconductors are visible through RIXS, thanks to the enhancement of valence charge excitations guaranteed by the resonance character of the technique.

This makes RIXS as the paramount technique to study magnon dispersions, thanks to the higher cross-section with respect to INS.

[1][40][39][41] Moreover, it has been theoretically shown that RIXS can probe Bogoliubov quasiparticles in high-temperature superconductors,[42] and shed light on the nature and symmetry of the electron-electron pairing of the superconducting state.

[44][45] The power of pump-probe spectroscopies lies in the possibility to study how a system evolves after an external stimulus.

The most straightforward example is the study of photoactivated biological process, such as the photosynthesis: the sample is illuminated by an optical laser tuned at the proper wavelength and then its evolution is observed taking snapshots as a function of time.