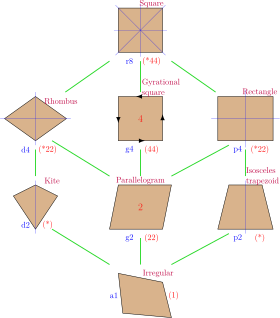

Rhombus

"[4] The word was used both by Euclid and Archimedes, who used the term "solid rhombus" for a bicone, two right circular cones sharing a common base.

[5] The surface we refer to as rhombus today is a cross section of the bicone on a plane through the apexes of the two cones.

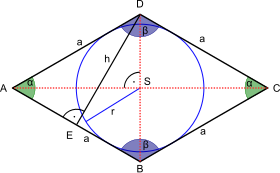

A rhombus therefore has all of the properties of a parallelogram: for example, opposite sides are parallel; adjacent angles are supplementary; the two diagonals bisect one another; any line through the midpoint bisects the area; and the sum of the squares of the sides equals the sum of the squares of the diagonals (the parallelogram law).

The length of the diagonals p = AC and q = BD can be expressed in terms of the rhombus side a and one vertex angle α as and These formulas are a direct consequence of the law of cosines.

Convex polyhedra with rhombi include the infinite set of rhombic zonohedrons, which can be seen as projective envelopes of hypercubes.