Rise of the Ottoman Empire

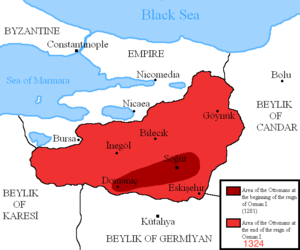

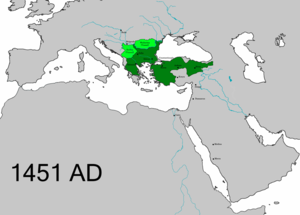

This period witnessed the foundation of a political entity ruled by the Ottoman Dynasty in the northwestern Anatolian region of Bithynia, and its transformation from a small principality on the Byzantine frontier into an empire spanning the Balkans, Anatolia, Middle East and North Africa.

[11] The fragmentation of authority has led several historians to describe the political entities of thirteenth and fourteenth-century Anatolia as Taifas, or "petty kings", a comparison with the history of late-medieval Muslim Spain.

Islam and Persian culture were part of Ottoman self-identity from the start, as evidenced by a land grant issued by Osman's son Orhan in 1324, describing him as "Champion of the Faith".

[23] Wittek's formulation, subsequently known as the "Gaza Thesis," was influential for much of the twentieth century, and led historians to portray the early Ottomans as zealous religious warriors dedicated to the spread of Islam.

[28] During this early period, before the Ottomans were able to establish a centralized system of government in the middle of the fifteenth century, the rulers' powers were "far more circumscribed, and depended heavily upon coalitions of support and alliances reached" among various power-holders within the empire, including Turkic tribal leaders and Balkan allies and vassals.

[33] It was also during the reign of Murad I that the office of military judge (Kazasker) was created, indicating an increasing level of social stratification between the emerging military-administrative class (askeri) and the rest of society.

[41] This work, entitled the İskendernāme, ("The Book of Alexander") was part of a genre known as "mirror for princes" (naṣīḥatnāme), meant to provide advice and guidance to the ruler with regard to statecraft.

Thus rather than providing a factual account of the dynasty's history, Ahmedi's goal was to indirectly criticize the sultan by depicting his ancestors as model rulers, in contrast to the perceived deviance of Bayezid.

Specifically, Ahmedi took issue with Bayezid's military campaigns against fellow Muslims in Anatolia, and thus depicted his ancestors as totally devoted to holy war against the Christian states of the Balkans.

[48] Early on, he attracted several notable figures to his side, including Köse Mihal, a Byzantine village headman whose descendants (known as the Mihaloğulları) enjoyed primacy among the frontier warriors in Ottoman service.

Köse Mihal was noteworthy for having been a Christian Greek; while he eventually converted to Islam, his prominent historical role indicates Osman's willingness to cooperate with non-Muslims and to incorporate them in his political enterprise.

The initial Thracian conquests placed the Ottomans strategically astride all of the major overland communication routes linking Constantinople to the Balkan frontiers, facilitating their expanded military operations.

[55][better source needed] By transferring his capital from Bursa in Anatolia to that newly won city in Thrace, Murad signaled his intentions to continue Ottoman expansion in Southeast Europe.

Before the conquest of Edirne, most Christian Europeans regarded the Ottoman presence in Thrace as merely the latest unpleasant episode in a long string of chaotic events in the Balkans.

Far from preserving Serb unity, Uroš's loosely amalgamated domains were wracked by constant civil war among the regional nobles, leaving Serbia vulnerable to the rising Ottoman threat.

As for Byzantium, Emperor John V definitively accepted Ottoman vassalage soon after the battle, opening the door to Murad's direct interference in Byzantine domestic politics.

1383-86), in 1385 Murad took Sofia, the last remaining Bulgarian possession south of the Balkan Mountains, opening the way toward strategically located Niš, the northern terminus of the important Vardar-Morava highway.

Confident because of the victory at Plocnik, the Serbian prince refused and turned to Tvrtko of Bosnia and Vuk Brankovic, his son-in-law and independent ruler of northern Macedonia and Kosovo, for aid against the certain Ottoman retaliatory offensive.

[58] Lazar's young and weak successor Stefan Lazarević (1389–1427) concluded a vassal agreement with Bayezid in 1390 to counter Hungarian moves into northern Serbia, while Vuk Branković, the last independent Serb prince, held out until 1392.

Both to secure the southern stretch of the Vardar-Morava highway and to establish a firm base for permanent expansion westward to the Adriatic coast, Bayezid settled large numbers of ‘’yürüks’’ along the Vardar River valley in Macedonia.

The appearance of Turk raiders at Hungary's southern borders awakened the Hungarian King Sigismund of Luxemburg (1387–1437) to the danger that the Ottomans posed to his kingdom, and he sought out Balkan allies for a new anti-Ottoman coalition.

Having dealt harshly and effectively with his disloyal Bulgarian vassals, Bayezid then turned his attention south to Thessaly and the Morea, whose Greek lords had accepted Ottoman vassalage in the 1380s.

In 1410 he was defeated and killed by his brother Musa, who won the Ottoman Balkans with the support of Byzantine Emperor Manuel II, Serbian Despot Stefan Lazarevic, Wallachian Voievod Mircea, and the two last Bulgarian rulers’ sons.

After the Balkan front was secured, Murad turned east and defeated Timur Lenk's son, Shah Rukh, and the emirates of Candar and Karaman in Anatolia.

But by conquering and annexing the emirate of Karamanid (May–June, 1451) and by renewing the peace treaties with Venice (September 10) and Hungary (November 20) Mehmed II proved his skills both on the military and the political front and was soon accepted by the noble class of the Ottoman court.

Older and a good deal wiser, he made capturing Constantinople his first priority, believing that it would solidify his power over the high military and administrative officials who had caused him such problems during his earlier reign.

Constantinople's location also made it the natural "middleman" center for both land and sea trade between the eastern Mediterranean and central Asia, possession of which would ensure immense wealth.

A trade agreement with Venice prevented the Venetians from intervening on behalf of the Byzantines, and the rest of Western Europe unwittingly cooperated with Mehmed's plans by being totally absorbed in internecine wars and political rivalries.

Although the city's defenders, led by Giovanni Giustiniani under Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos's (1448–53) authority, put up a heroic defense, without the benefit of outside aid their efforts were doomed.

Newly conquered Constantinople rapidly grew into a multiethnic, multicultured, and bustling economic, political, and cultural center for the Ottoman state,[citation needed] whose distant frontiers guaranteed it peace, security, and prosperity.