Spacecraft propulsion

Russian and antecedent Soviet bloc satellites have used electric propulsion for decades,[1] and newer Western geo-orbiting spacecraft are starting to use them for north–south station-keeping and orbit raising.

[2][3][4] Space exploration is about reaching the destination safely (mission enabling), quickly (reduced transit times), with a large quantity of payload mass, and relatively inexpensively (lower cost).

When launching a spacecraft from Earth, a propulsion method must overcome a higher gravitational pull to provide a positive net acceleration.

[17] Some designs however, operate without internal reaction mass by taking advantage of magnetic fields or light pressure to change the spacecraft's momentum.

When discussing the efficiency of a propulsion system, designers often focus on the effective use of the reaction mass, which must be carried along with the rocket and is irretrievably consumed when used.

[18] Spacecraft performance can be quantified in amount of change in momentum per unit of propellant consumed, also called specific impulse.

, mission planners are increasingly willing to sacrifice power and thrust (and the extra time it will take to get a spacecraft where it needs to go) in order to save large amounts of propellant mass.

Once in the desired orbit, they often need some form of attitude control so that they are correctly pointed with respect to the Earth, the Sun, and possibly some astronomical object of interest.

[34] No spacecraft capable of short duration (compared to human lifetime) interstellar travel has yet been built, but many hypothetical designs have been discussed.

[44] The extremely hot gas is then allowed to escape through a high-expansion ratio bell-shaped nozzle, a feature that gives a rocket engine its characteristic shape.

[citation needed] The dominant form of chemical propulsion for satellites has historically been hydrazine, however, this fuel is highly toxic and at risk of being banned across Europe.

Nitrous oxide-based alternatives are garnering traction and government support,[47][48] with development being led by commercial companies Dawn Aerospace, Impulse Space,[49] and Launcher.

[53] Such an engine uses electric power, first to ionize atoms, and then to create a voltage gradient to accelerate the ions to high exhaust velocities.

[citation needed] Their very high exhaust velocity means they require huge amounts of energy and thus with practical power sources provide low thrust, but use hardly any fuel.

[55] However, they generally have very small values of thrust and therefore must be operated for long durations to provide the total impulse required by a mission.

[63] Current nuclear power generators are approximately half the weight of solar panels per watt of energy supplied, at terrestrial distances from the Sun.

Non-conservative external forces, primarily gravitational and atmospheric, can contribute up to several degrees per day to angular momentum,[70] so such systems are designed to "bleed off" undesired rotational energies built up over time.

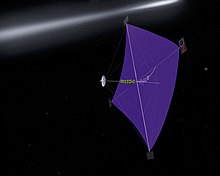

[citation needed] The concept of solar sails rely on radiation pressure from electromagnetic energy, but they require a large collection surface to function effectively.

Japan launched a solar sail-powered spacecraft, IKAROS in May 2010, which successfully demonstrated propulsion and guidance (and is still active as of this date).[when?

A tether propulsion system employs a long cable with a high tensile strength to change a spacecraft's orbit, such as by interaction with a planet's magnetic field or through momentum exchange with another object.

[82] Advanced, and in some cases theoretical, propulsion technologies may use chemical or nonchemical physics to produce thrust but are generally considered to be of lower technical maturity with challenges that have not been overcome.

The most distant planets are 4.5–6 billion kilometers from the Sun and to reach them in any reasonable time requires much more capable propulsion systems than conventional chemical rockets.

The logistics, and therefore the total system mass required to support sustained human exploration beyond Earth to destinations such as the Moon, Mars, or near-Earth objects, are daunting unless more efficient in-space propulsion technologies are developed and fielded.

A variety of hypothetical propulsion techniques have been considered that require a deeper understanding of the properties of space, particularly inertial frames and the vacuum state.

[citation needed] Table NotesThere have been many ideas proposed for launch-assist mechanisms that have the potential of substantially reducing the cost of getting to orbit.

Proposed non-rocket spacelaunch launch-assist mechanisms include:[110][111] Studies generally show that conventional air-breathing engines, such as ramjets or turbojets are basically too heavy (have too low a thrust/weight ratio) to give significant performance improvement when installed on a launch vehicle.

[citation needed] On the other hand, very lightweight or very high-speed engines have been proposed that take advantage of the air during ascent: Normal rocket launch vehicles fly almost vertically before rolling over at an altitude of some tens of kilometers before burning sideways for orbit; this initial vertical climb wastes propellant but is optimal as it greatly reduces airdrag.

The vehicles would typically fly approximately tangentially to Earth's surface until leaving the atmosphere then perform a rocket burn to bridge the final delta-v to orbital velocity.

[5][4] One institution focused on developing primary propulsion technologies aimed at benefitting near and mid-term science missions by reducing cost, mass, and/or travel times is the Glenn Research Center (GRC).

A successful validation flight would not require any additional space testing of a particular technology before it can be adopted for a science or exploration mission.