Rogerian argument

For example, they concluded that Rogerian argument is less likely to be appropriate or effective when communicating with violent or discriminatory people or institutions, in situations of social exclusion or extreme power inequality, or in judicial settings that use formal adversarial procedures.

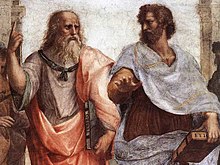

They borrowed the term Rogerian and related ideas from the polymath Anatol Rapoport,[6][7] who was working, and doing peace activism, at the same university.

[9] The University of Texas at Austin professor Maxine Hairston then spread Rogerian argument through publications such as her textbook A Contemporary Rhetoric,[10] and other authors published book chapters and scholarly articles on the subject.

[11] He noted that they correspond to three kinds of psychotherapy or ways of changing people,[12] and he named them after Pavlov (behaviorism), Freud (psychoanalysis), and Rogers (person-centered therapy).

Young, Becker, and Pike's 1970 textbook Rhetoric: Discovery and Change said that the strategies correspond to three big assumptions about humanity, which they called three "images of man".

[13][18] Rapoport considered this strategy to be at the core of Freudian psychoanalysis but also to be present in any other kind of analysis that aims to change people's minds or behaviors by explaining how their beliefs or discourse are a product of hidden motives or mechanisms.

[20] Such "explaining away" or "debunking" of people's beliefs and behaviors may work, Rapoport said, when there is "a complete trust placed by the target of persuasion in the persuader", as sometimes occurs in teaching and psychotherapy.

"[25] Rapoport suggested three principles that characterize the Rogerian strategy: listening and making the other feel understood, finding merit in the other's position, and increasing the perception of similarity between people.

[26] A work by Carl Rogers that was especially influential in the formulation of Rogerian argument was his 1951 paper "Communication: Its Blocking and Its Facilitation",[27] published in the same year as his book Client-Centered Therapy.

[33] One idea that Rogers emphasized several times in his 1951 paper that is not mentioned in textbook treatments of Rogerian argument is third-party intervention.

[41] English professor Andrea Lunsford, responding to Young, Becker, and Pike in a 1979 article, argued that the three principles of Rogerian strategy that they borrowed from Rapoport could be found in various parts of Aristotle's writings, and so were already in the classical tradition.

[46] English professor Paul G. Bator argued in 1980 that Rogerian argument is more different from Aristotle's rhetoric than Lunsford had concluded.

[49] Professor of communication Douglas Brent said that Rogerian rhetoric is not the captatio benevolentiae (securing of good will) taught by Cicero and later by medieval rhetoricians.

[50] Brent said that superficially confusing the Rogerian strategy with such ingratiation overlooks "the therapeutic roots of Rogers' philosophy", rhetoric's power to heal both speakers and listeners, and the importance of "genuine grounds of shared understanding, not just as a precursor to an 'effective' argument, but as a means of engaging in effective knowledge-making".

Philosopher Daniel Dennett, in his 2013 book Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking, called these principles Rapoport's rules of debate,[54] a term that other authors have since adopted.

[70] In a summary of Dennett's version of Rapoport's rules, Peter Boghossian and James A. Lindsay pointed out that an important part of how Rapoport's rules work is by modeling prosocial behavior: one party demonstrates respect and intellectual openness so that the other party can emulate those characteristics, which would be less likely to occur in intensely adversarial conditions.

[73] Austin summarized Axelrod's conclusion that Rapoport's tit-for-tat algorithm won those tournaments because it was (in a technical sense) nice, forgiving, not envious, and absolutely predictable.

[74] With these characteristics, tit-for-tat elicited mutually rewarding outcomes more than any of the competing algorithms did over many automated repetitions of the prisoner's dilemma game.

[78] Rapoport distinguished three hierarchical levels of conflict: Rapoport pointed out "that a rigorous examination of game-like conflict leads inevitably" to the examination of debates, because "strictly rigorous game theory when extrapolated to cover other than two-person zero-sum games" requires consideration of issues such as "communication theory, psychology, even ethics" that are beyond simple game-like rules.

[86] The third of Rapoport's principles—increasing the perceived similarity between self and other—is a principle that Young, Becker, and Pike considered to be equally as important as the other two, but they said it should be an attitude assumed throughout the discourse and is not a phase of writing.

[89] She said that the Rogerian approach requires calm, patience, and effort, and will work if one is "more concerned about increasing understanding and communication" than "about scoring a triumph".

[90] In a related article, she noted the similarity between Rogerian argument and John Stuart Mill's well-known phrase from On Liberty: "He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.

"[109] (Soon after, in opposition to Status belligerens, Rapoport relocated permanently to Canada from the United States,[110] leaving behind research connections with the military that he had since the 1940s.

[111]) Young, Becker, and Pike pointed out in 1970 that Rogerian argument would be out of place in the typical mandated adversarial criminal procedures of the court system in the United States.

[117] For women who are marginalized and have been taught that they are not "worthy opponents", Lassner said, "Rogerian rhetoric can be just as inhibiting and constraining as any other form of argumentation.

"[118] Some of Lassner's students doubted that their opponent (such as an anti-gay or anti-abortion advocate) could even recognize them or could conceal repugnance and rejection of them enough to make Rogerian empathy possible.

[129][130][131] Negotiation expert William Ury said in his 1999 book The Third Side that role reversal as a formal rule of argumentation has been used at least since the Middle Ages in the Western world: "Another rule dates back at least as far as the Middle Ages, when theologians at the University of Paris used it to facilitate mutual understanding: One can speak only after one has repeated what the other side has said to that person's satisfaction.