Rolling resistance

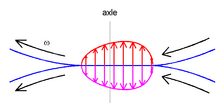

It is mainly caused by non-elastic effects; that is, not all the energy needed for deformation (or movement) of the wheel, roadbed, etc., is recovered when the pressure is removed.

Two forms of this are hysteresis losses (see below), and permanent (plastic) deformation of the object or the surface (e.g. soil).

Analogous with sliding friction, rolling resistance is often expressed as a coefficient times the normal force.

[2] Any coasting wheeled vehicle will gradually slow down due to rolling resistance including that of the bearings, but a train car with steel wheels running on steel rails will roll farther than a bus of the same mass with rubber tires running on tarmac/asphalt.

The losses due to hysteresis also depend strongly on the material properties of the wheel or tire and the surface.

As the tire rotates under the weight of the vehicle, it experiences repeated cycles of deformation and recovery, and it dissipates the hysteresis energy loss as heat.

Hysteresis is the main cause of energy loss associated with rolling resistance and is attributed to the viscoelastic characteristics of the rubber.

The line of action of the (aggregate) vertical force no longer passes through the centers of the cylinders.

Materials that have a large hysteresis effect, such as rubber, which bounce back slowly, exhibit more rolling resistance than materials with a small hysteresis effect that bounce back more quickly and more completely, such as steel or silica.

Low rolling resistance tires typically incorporate silica in place of carbon black in their tread compounds to reduce low-frequency hysteresis without compromising traction.

But there is an even broader sense that would include energy wasted by wheel slippage due to the torque applied from the engine.

The pure "rolling resistance" for a train is that which happens due to deformation and possible minor sliding at the wheel-road contact.

The train's engines must, of course, provide the energy to overcome this broad-sense rolling resistance.

Multiply it by 100 and you get the percent (%) of the weight of the vehicle required to maintain slow steady speed.

but does not explicitly show any variation with speed, loads, torque, surface roughness, diameter, tire inflation/wear, etc., because

The coefficient of rolling resistance for a slow rigid wheel on a perfectly elastic surface, not adjusted for velocity, can be calculated by [18][citation needed]

and maintain steady speed on level ground (with no air resistance) can be calculated by:

It is notable that slip does not occur in driven wheels, which are not subjected to driving torque, under different conditions except braking.

[45] Significance of rolling or slip resistance is largely dependent on the tractive force, coefficient of friction, normal load, etc.

For example, for pneumatic tires, a 5% slip can translate into a 200% increase in rolling resistance.

So just a small percentage increase in circumferential velocity due to slip can translate into a loss of traction power which may even exceed the power loss due to basic (ordinary) rolling resistance.

For railroads, this effect may be even more pronounced due to the low rolling resistance of steel wheels.

Slip (also known as creep) is normally roughly directly proportional to tractive effort.

At high torques, which apply a tangential force to the road of about half the weight of the vehicle, the rolling resistance may triple (a 200% increase).

The rolling resistance coefficient, Crr, significantly decreases as the weight of the rail car per wheel increases.

One of the most common examples of rolling friction is the movement of motor vehicle tires on a roadway, a process which generates sound as a by-product.

[54] The sound generated by automobile and truck tires as they roll (especially noticeable at highway speeds) is mostly due to the percussion of the tire treads, and compression (and subsequent decompression) of air temporarily captured within the treads.

Railroads normally use roller bearings which are either cylindrical (Russia)[63] or tapered (United States).

[64] The specific rolling resistance in bearings varies with both wheel loading and speed.

This means that for an Amtrak passenger train in 1975, much of the energy savings of the lower rolling resistance was lost to its greater weight.