Slavery in ancient Rome

[39] The loss of citizenship was a consequence of submitting to an enemy sovereign state; freeborn people kidnapped by bandits or pirates were regarded as seized illegally, and therefore they could be ransomed, or their sale into slavery rendered void, without compromising their citizen status.

[54] Agricultural slaves, certain farmland within the Italian peninsula, and farm animals were all res mancipi, a category of property established in early Rome's rural economy as requiring a formal legal process (mancipatio) for transferring ownership.

[83] But because of the value Romans placed on home-reared slaves (vernae) in expanding their familia,[84] there is more evidence that the formation of family units, though not recognized as such for purposes of law and inheritance, was supported within larger urban households and on rural estates.

[149] The Lex Aelia Sentia of AD 4 allowed a patron to take his freedman to court for not carrying out his operae as outlined in their manumission agreement, but the possible penalties—which range in severity from a reprimand and fines to condemnation to hard labor—never include a return to enslavement.

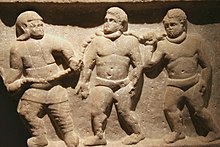

[192] The cultural assumption that enslavement was a natural result of defeat in war is reflected in the ubiquity of Imperial art depicting captives, an image that appears not only in public contexts that serve overt purposes of propaganda and triumphalism but also on objects that seem intended for household and personal display, such as figurines, lamps, Arretine pottery, and gems.

[233] Jobs for which child slaves apprenticed include textile production, metalworking such as nail-making and coppersmithing, mirror-making, shorthand and other secretarial skills, accounting, music and the arts, baking, ornamental gardening, and construction techniques.

[256] Child abandonment, whether through the death of family or intentionally, is to be distinguished from infant exposure (expositio), which the Romans seem to have practiced widely and which is embedded in the founding myth of the exposed twins Romulus and Remus suckling at the she-wolf.

At a time when infant mortality might have been as high as 40 percent,[269] the newborn was thought in its first week of life to be in a perilous liminal state between biological existence and social birth,[270] and the first bath was one of many rituals marking this transition and supporting the mother and child.

[271] The Constantinian law has been viewed as an effort to stop the practice of exposure as infanticide[272] or as "an insurance policy on behalf of individual slave-owners"[273] designed to protect the property of those who, unknowingly or not, had bought an infant later claimed or shown to have been born free.

Constantine, the first Christian emperor, tried to alleviate hunger as one condition that led to child-selling by ordering local magistrates to distribute free grain to poor families,[288] later abolishing the "power of life and death" the paterfamilias had held.

[343][344] Roman coin hoards dating from the 60s BC are found in unusual abundance in Dacia (present-day Romania), and have been interpreted as evidence that Pompey's success in shutting down piracy caused an increase in the slave trade in the lower Danube basin to meet demand.

[351] Walter Scheidel conjectured that "enslavables" were traded across borders from present-day Ireland, Scotland, eastern Germany, southern Russia, the Caucasus, the Arab peninsula, and what used to be referred to as "the Sudan"; the Parthian Empire would have consumed most supply to the east.

[392] Mark Antony relied on Toranius as a procurer of female slaves, and even forgave him upon learning that the supposedly twin boys he had purchased were in fact not consanguineous, the mango having persuaded the triumvir that their identical appearance was therefore all the more remarkable.

[411] A law of the censors exempted the paterfamilias from paying harbor tax at Sicily on servi brought into Italy for his direct employment in a wide range of roles, indicating that the Romans saw a difference between obtaining slaves who were to be incorporated into the life of the household and those traded for profit.

[citation needed] Legal texts state that slaves' skills were to be protected from misuse; examples given include not using a stage actor as a bath attendant, not forcing a professional athlete to clean latrines, and not sending a librarius (scribe or manuscript copyist) to the countryside to carry baskets of lime.

[416] Epitaphs record at least 55 different jobs a household slave might have,[413] including barber, butler, cook, hairdresser, handmaid (ancilla), launderer, wet nurse or nursery attendant, teacher, secretary, seamstress, accountant, and physician.

[417] Rich households with specialists who might not be needed full-time year round, such as goldsmiths or furniture painters, might lease them out to friends and desirable associates or give them license to run their own shop as part of their peculium.

[428] The contractual aspect of benefits and obligations seems "distinctly modern"[429] and indicates that a slave on a skills track might have opportunities, bargaining power, and relative social security nearly on a par with or exceeding free but low-skill workers living at a subsistence level.

[459] The Imperial novelty of sentencing free people to hard labor may have compensated for a declining supply of war captives to enslave, though ancient sources don't discuss the economic impact as such, which was secondary to demonstrating the "coercive capacities of the state"—the cruelty was the point.

The employee agrees to provide "healthy and vigorous labor" at a gold mine for wages of 70 denarii and a term of service from May to November; if he chooses to quit before that time, 5 sesterces for each day not worked will be deducted from the total.

[674] But its leader, Spartacus, arguably the most famous slave from all antiquity and idealized by Marxist historians and creative artists, has captured the popular imagination over the centuries to such an extent that an understanding of the rebellion beyond his tactical victories is hard to retrieve from the various ideologies it has served.

[715] Unless the excessive cruelty had been blatantly public, there was no process for bringing it to the attention of the authorities—the slave boy targeted by Vedius was saved extrajudicially by the chance presence of an emperor willing to be offended,[716] the only person with the authority to stop what was allowed by law.

[719] This definition holds into the early Imperial era as a common understanding: in the Acts of the Apostles, when Paul asserts his rights as a Roman citizen to a centurion after having been bound and threatened with flogging, the tribune who has seized him acknowledges the error by backing off.

As a category of legal status, after the Augustan law that created a class of slaves to be counted permanently among the dediticii who were technically free but held no rights, the servus vinctus was barred from obtaining citizenship even if manumitted.

[736] Literature alludes to the practice, as when the epigrammatist Martial satirizes a luxuriously attired freedman at the theater who keeps his inscribed forehead under wraps, and Libanius mentions a slave growing out bangs to cover his stigmata.

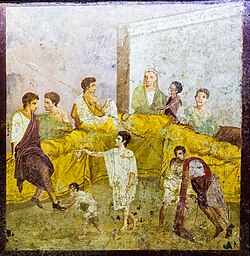

Both Solinus and Macrobius see the feast as a way to manipulate obedience, indicating that physical compulsion was not the only technique for domination; social theory suggests that the communal meal also promotes household cohesion and norms by articulating the hierarchy through its temporary subversion.

[824] The slave Vitalis is known from three inscriptions involving the cult of Mithras at Apulum (Alba Iulia in present-day Romania).The best preserved is the dedication of an altar to Sol Invictus for the wellbeing of a free man, possibly his master or a fellow Mithraic initiate.

Despite these realistic details of his craft, Agatho is depicted wearing a toga—which Getty Museum curator Kenneth Lapatin has compared to going to work in a tuxedo—that expresses his pride in his citizen status,[834] just as the choice of marble as the medium rather than the more common limestone gives evidence of his level of success.

[897] Some household staff, such as cup-bearers for dinner parties, generally boys, were chosen at a young age for their grace and good looks, qualities that were cultivated, sometimes through formal training, to convey sexual allure and potential use by guests.

[903] Roman art connoisseurs did not shy away from displaying explicit sexuality in their collections at home,[904] but when figures identifiable as slaves appear in erotic paintings within a domestic scenario, they are either hovering in the background or performing routine peripheral tasks, not engaging in sex.