Francis Crick

[5] Together with Maurice Wilkins, they were jointly awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material".

He was born on 8 June 1916[4] and raised in Weston Favell, then a small village near the English town of Northampton, in which Crick's father and uncle ran the family's boot and shoe factory.

His grandfather, Walter Drawbridge Crick, an amateur naturalist, wrote a survey of local foraminifera (single-celled protists with shells), corresponded with Charles Darwin,[9] and had two gastropods (snails or slugs) named after him.

Crick began a PhD research project on measuring the viscosity of water at high temperatures (which he later described as "the dullest problem imaginable"[13]) in the laboratory of physicist Edward Neville da Costa Andrade at University College London, but with the outbreak of World War II (in particular, an incident during the Battle of Britain when a bomb fell through the roof of the laboratory and destroyed his experimental apparatus),[2] Crick was deflected from a possible career in physics.

This migration was made possible by the newly won influence of physicists such as Sir John Randall, who had helped win the war with inventions such as radar.

Crick felt that this attitude encouraged him to be more daring than typical biologists who tended to concern themselves with the daunting problems of biology and not the past successes of physics[citation needed].

[18] Spouses: Children: Crick died of colon cancer on the morning of 28 July 2004[4] at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Thornton Hospital in La Jolla; he was cremated and his ashes were scattered into the Pacific Ocean.

A public memorial was held on 27 September 2004 at the Salk Institute, La Jolla, near San Diego, California; guest speakers included James Watson, Sydney Brenner, Alex Rich, Seymour Benzer, Aaron Klug, Christof Koch, Pat Churchland, Vilayanur Ramachandran, Tomaso Poggio, Leslie Orgel, Terry Sejnowski, his son Michael Crick, and his younger daughter Jacqueline Nichols.

[29] Crick was in the right place, in the right frame of mind, at the right time (1949), to join Max Perutz's project at the University of Cambridge, and he began to work on the X-ray crystallography of proteins.

[31] During the period of Crick's study of X-ray diffraction, researchers in the Cambridge lab were attempting to determine the most stable helical conformation of amino acid chains in proteins (the alpha helix).

Crick was witness to the kinds of errors that his co-workers made in their failed attempts to make a correct molecular model of the alpha helix; these turned out to be important lessons that could be applied, in the future, to the helical structure of DNA.

Crick described what he saw as the failure of Wilkins and Franklin to cooperate and work towards finding a molecular model of DNA as a major reason why he and Watson eventually made a second attempt to do so.

The key problem for Watson and Crick, which could not be resolved by the data from King's College, was to guess how the nucleotide bases pack into the core of the DNA double helix.

Identification of the correct base-pairing rules (A-T, G-C) was achieved by Watson "playing" with cardboard cut-out models of the nucleotide bases, much in the manner that Linus Pauling had discovered the protein alpha helix a few years earlier.

The Watson and Crick discovery of the DNA double helix structure was made possible by their willingness to combine theory, modelling and experimental results (albeit mostly done by others) to achieve their goal.

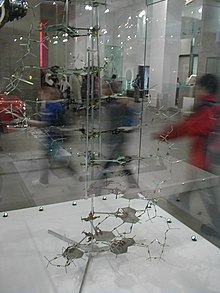

[53] Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Dorothy Hodgkin, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M Oughton, were some of the first people in April 1953 to see the model of the structure of DNA, constructed by Crick and Watson; at the time they were working at Oxford University's Chemistry Department.

By 1958, Crick's thinking had matured and he could list in an orderly way all of the key features of the protein synthesis process:[7] The adaptor molecules were eventually shown to be tRNAs and the catalytic "ribonucleic-protein complexes" became known as ribosomes.

In his thinking about the biological processes linking DNA genes to proteins, Crick made explicit the distinction between the materials involved, the energy required, and the information flow.

Wilkins turned down the offer, a fact that may have led to the terse character of the acknowledgement of experimental work done at King's College in the eventual published paper.

Franklin subsequently did superb work in J. D. Bernal's Lab at Birkbeck College with the tobacco mosaic virus, which also extended ideas on helical construction.

Crick's view of the relationship between science and religion continued to play a role in his work as he made the transition from molecular biology research into theoretical neuroscience.

In the 1987 United States Supreme Court case Edwards v. Aguillard, Crick joined a group of other Nobel laureates who advised, "'Creation-science' simply has no place in the public-school science classroom.

In the early 1970s, Crick and Orgel further speculated about the possibility that the production of living systems from molecules may have been a very rare event in the universe, but once it had developed it could be spread by intelligent life forms using space travel technology, a process they called "directed panspermia".

[112] In a retrospective article,[113] Crick and Orgel noted that they had been unduly pessimistic about the chances of abiogenesis on Earth when they had assumed that some kind of self-replicating protein system was the molecular origin of life.

[citation needed]The apparently "pretty well kept secret" had already been recorded in Soraya De Chadarevian's Designs For Life: Molecular Biology After World War II, published by Cambridge University Press in 2002.

His autobiographical book, What Mad Pursuit: A Personal View of Scientific Discovery, includes a description of why he left molecular biology and switched to neuroscience.

In the final phase of his career, Crick established a collaboration with Christof Koch that led to publication of a series of articles on consciousness during the period spanning from 1990[120] to 2005.

Crick made the strategic decision to focus his theoretical investigation of consciousness on how the brain generates visual awareness within a few hundred milliseconds of viewing a scene.

In his book The Astonishing Hypothesis, Crick described how neurobiology had reached a mature enough stage so that consciousness could be the subject of a unified effort to study it at the molecular, cellular and behavioural levels.

[126] The Francis Crick Medal and Lecture[127] was established in 2003 following an endowment by his former colleague, Sydney Brenner, joint winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.