Rural American history

[1] According to Robert P. Swierenga, " Rural history centers on the lifestyle and activities of farmers and their family patterns, farming practices, social structures, political ties, and community institutions.

For example in his history of agriculture in Wisconsin, Jerry Apps includes a wide range of topics: Environmental preconditions; the Native American experience, the original Yankee settlers; lead mining; the rise and fall of wheat; the role of steamboats and railroads; relation of rural and urban trends; lumbering; early mechanization; German, Swiss and Scandinavian immigration; the growth of cities; farmers in local and state government and politics; rural schools; transition to crop agriculture; the cheese and dairy industry; farming as a business; the Wisconsin idea; the College of Agriculture outreach programs; automobiles and good roads; tractors replace horses; arrival of rural free delivery, electricity and telephone; livestock raising; cranberry growing; federal controls and subsidies; truck farming; irrigation; consolidation into mega farms; the farm crisis of the 1980s; environmental degradation and recovery; and the impact of high tech.

Ever since the battles between Jeffersonian Republicans against Hamiltonian Federalists, the conflict between localism and cosmopolitanism has provided clues to understand the defensiveness of rural America.

Typically they exchanged their small surpluses of food or tobacco or rice or lumber for imported items with the country merchant at a nearby crossroads.

The first stage of industrialization came in rural towns in New England in the early 19th century when they started to use water power from its rivers to run the machinery in mills that turned wool and cotton into thread and cloth.

[33] [34][35] In the colonial era, access to natural resources was allocated by individual towns, and disputes over fisheries or land use were resolved at the local level.

Changing technologies, however, strained traditional ways of resolving disputes of resource use, and local governments had limited control over powerful special interests.

In New England, many farmers became uneasy as they noticed clearing of the forest changed stream flows and a decrease in bird population which helped control insects and other pests.

[40] Farmers and ranchers depended on general stores that had a limited stock and slow turnover; they made enough profit to stay in operation by selling at high prices.

The American Civil War devastated the rural, as cotton prices fell and the vast sums invested in slaves disappeared overnight.

[43] Before the Civil War plantation owners handled the cotton or tobacco matters and met consumer needs of their family and slaves.

In one Florida store with a largely Black clientele, the items most often purchased were corn, salt pork, sugar, lard, coffee, syrup, rice, flour, cloth, shoes, shotguns, shells, and patent medicines.

Merchants depended on credit from urban wholesalers, and like the sharecroppers they paid off their own debts with proceeds from the cotton or tobacco harvests.

However, the paper also contained local news, and presented literary columns and book excerpts that catered to an emerging middle class literate audience.

Most famously the Weekly New York Tribune was jammed with political, economic and cultural news and features, and was a major resource for the local Whig and Republican press.

[66] [67][68] Historian Wayne Flynt notes that rural evangelists in the 19th century significantly supported various political movements challenging the established powers.

Starting with the Primitive Baptists who aligned with Jacksonian democracy, rural evangelicals provided critical support to several large-scale uprisings towards the end of the 19th century, such as the Greenback Labor Party, the Grangers, Farmers Alliances, and most notably the Populists of the 1890s.

Southern rural evangelists by the hundreds of thousands could serve as a powerful catalyst for both progressive change and rustic radicalism, for social justice, as well as for racism and traditionalism.

He called for "free silver", a device to pump cash into the rural economy to raise prices, regardless of its negative impact on urban wages.

[76] In Iowa the incoming Republican governor proclaimed in 1898: "Our industrial and financial skies are brightening [after] the experience of unrest, distrust, doubt, fear, disaster, and much of ruin, through which we have passed.

[83] By 1900 prosperity had indeed returned, and a smashing victory against Spain in a short, popular war guaranteed McKinley's landslide reelection against Bryan.

[85][86] 1900-1914 was a golden age that rural spokesmen used as the ideal standard for the "doctrine of parity" that shaped federal policy for the rest of the 20th century.

They created swirls of dust in the summer, froze into hard grooves in the winter, and transformed into swamps each spring and fall, ensnaring even the strongest horses and the mighty Model T. Agricultural goods could only be sold profitably if they were close to railroad or water transport hubs; carts and wagons couldn't withstand the relentless pressure of the bumpy roads.

Farm horses were unable to handle the continuous effort of trudging through mud, and farmers couldn't afford the time to make long journeys.

Starting in 1908 farmers took the lead in buying Ford Model T automobiles, making it much easier to bring in supplies and haul out items to sell.

The Post Office entered the fray with Rural Free Delivery in 1906, which enabled farmers to order cheap consumer items from fat catalogs sent out by Montgomery Ward and Sears.

[100] The South has had a majority of its population adhering to evangelical Protestantism ever since the early 1800s as a result of the Second Great Awakening,[101] The upper classes often stayed Episcopalian or Presbyterian.

They included tens of thousands of members and numerous clergymen and staffers, all controlled by a charismatic minister whose word is gospel as he promises prosperity to God's people.

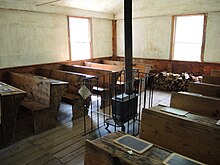

Jensen and Friedberger (1976) have examined the impact of education on various socioeconomic factors in Iowa from 1870 to 1930, using individual data from state and federal census manuscripts.

Despite the emergence of modern educational mobility channels, traditional opportunities through property accumulation remained more attractive to the average Iowan during this period.