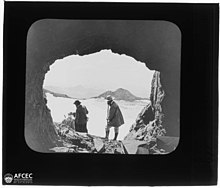

Russell Caves

From then on, he had a special relationship with this peak, making what is considered Europe's first major winter ascent on February 11, 1869, with guides Hippolyte and Henri Passet.

[5] Buried inside his lambskin rucksack, in a small ditch covered with stones, Henry Russell fell asleep only briefly due to the negative temperature, but he experienced one of the most beautiful moments of his life, amazed by the spectacle of the starry night as well as that of the sunrise.

[5][6] This experience made him want to spend long periods at high altitude, and he realized that his age was making it difficult for him to keep up the mountain runs with a minimum of sleep and food.

[10] Once the contract had been signed, Theil and his workers began work in August, but progress was slow due to the hardness of the rock: after a few days, only a hole of around one cubic meter had been dug.

[10] The following year, one of the workers, Justin Pontet, put forward the idea of setting up a forge near the site, to maintain the tools, which were rapidly becoming blunt.

[10] As soon as they received the cave, which was named "Villa Russell", its owner decided to spend three days there in the company of a young English mountaineer, Francis-Edward-Lister Swan, and three guides and porters, Henri Passet, Mathieu Haurine, and Pierre Pujo.

[10] On August 4, Jean Bazillac and Henri Brulle, completing a Pyrenean excursion to the Vignemale that had begun a few weeks earlier, made their way to Villa Russell, narrowly missing the Count and his guests, who had left the day before.

For ten days in early August, more than 80 guests enjoyed the Count's hospitality, bringing him gifts of tea, Bordeaux wine, Madeira, and Port.

On August 11, the "Villa Russell", transformed into a chapel for the event, was blessed by priests from Lourdes, Héas, and Saint-Savin, a consecration reported in regional newspapers.

[15] Russell further increased his accommodation capacity the following year with the construction of a third shelter, the "Grotte des Dames", built 4 meters above the previous ones, whose entrance was regularly blocked by the advancing Ossoue glacier.

On August 6, 1888, his friends Roger de Monts and Jean Bazillac sent for a tent, beds, armchairs, books, lanterns, banners, Eskimo costumess and plenty of food.

He applied to the Barèges valley syndicate commission for a concession that would give him symbolic ownership of all the snow and rock above 2,300 meters, for a total of 200 hectares around the massif.

[21] Meeting on February 25, 1889, the syndicate commission, considering that this proposal could be beneficial for the development of tourism in the region, unanimously decided to accept Count Russell's offer.

In 1894, he made his twenty-fifth ascent of the Vignemale, celebrating what he called his "silver wedding" with the summit, in the company of his friend Bertrand de Lassus and guides Henri Passet, Mathieu Haurine, and François Bernat-Salles.

During this final seventeen-day stay on his beloved mountain, he observed the spectacular melting of the Ossoue glacier and had a small, three-meter-high square tower built to rectify the summit's altitude by raising it above 3,300 meters.

[28] To welcome his guests, the Count systematically provides hot beverages such as soup, tea, chocolate, coffee, or punch-brûlant, as well as numerous canned solid foods.

Henry Russell evokes the splendor of these gastronomic meals at high altitude in an article entitled "L'Avenir du Vignemale", published in the Gazette de Cauterets on August 5, 1886.

In it, he humorously imagines the discovery of the caves a thousand years later by a geologist and his students:[32] The Professor, in white tie, eyes upwards, in a long black frock coat (if one is still wearing one), and in a masterly tone: "In these places, everything speaks to us of the sea: everything recalls it.

Then, as the sea level dropped, the caves left on the shore were inhabited by dreadful troglodytes (perhaps by dreadful brigands...), who, as you can see, lived on the edge of the ocean, since there are pieces of petrified lobster, traces of herring, a few traces of sardine everywhere" [...] Excuse me, sir, but here's a trout bone, a fish that can only live in fresh water!!!!

[36] In 2021, an association, in partnership with the Parc National des Pyrénées, restored the sundial that Count Russell had placed on the side of one of Bellevue's caves.