Bohr model

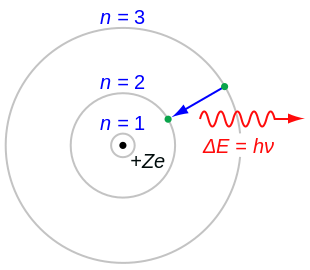

It is analogous to the structure of the Solar System, but with attraction provided by electrostatic force rather than gravity, and with the electron energies quantized (assuming only discrete values).

The improvement over the 1911 Rutherford model mainly concerned the new quantum mechanical interpretation introduced by Haas and Nicholson, but forsaking any attempt to explain radiation according to classical physics.

However, because of its simplicity, and its correct results for selected systems (see below for application), the Bohr model is still commonly taught to introduce students to quantum mechanics or energy level diagrams before moving on to the more accurate, but more complex, valence shell atom.

[5]: 18 In 1908, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden demonstrated that alpha particle occasionally scatter at large angles, a result inconsistent with Thomson's model.

[15]: 847 [16] In 1910, Arthur Erich Haas proposed a model of the hydrogen atom with an electron circulating on the surface of a sphere of positive charge.

Bohr took the Planck constant as given value and used the equations to predict, a, the radius of the electron orbiting in the ground state of the hydrogen atom.

[17]: 273 While Bohr had already expressed a similar opinion in his PhD thesis, at Solvay the leading scientists of the day discussed a break with classical theories.

When he then learned from a friend about Balmer's compact formula for the spectral line data, Bohr quickly realized his model would match it in detail.

[20]: 163 By 1913 Bohr had already shown, from the analysis of alpha particle energy loss, that hydrogen had only a single electron not a matched pair.

Another form of the same theory, wave mechanics, was discovered by the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger independently, and by different reasoning.

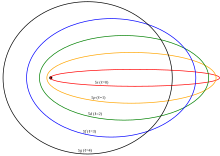

Bohr assumes that the electron is circling the nucleus in an elliptical orbit obeying the rules of classical mechanics, but with no loss of radiation due to the Larmor formula.

(4) stems from the virial theorem, and from the classical mechanics relationships between the angular momentum, the kinetic energy and the frequency of revolution.

[25] The combination of natural constants in the energy formula is called the Rydberg energy (RE): This expression is clarified by interpreting it in combinations that form more natural units: Since this derivation is with the assumption that the nucleus is orbited by one electron, we can generalize this result by letting the nucleus have a charge q = Ze, where Z is the atomic number.

Sufficiently large nuclei, if they were stable, would reduce their charge by creating a bound electron from the vacuum, ejecting the positron to infinity.

This fact was historically important in convincing Rutherford of the importance of Bohr's model, for it explained the fact that the frequencies of lines in the spectra for singly ionized helium do not differ from those of hydrogen by a factor of exactly 4, but rather by 4 times the ratio of the reduced mass for the hydrogen vs. the helium systems, which was much closer to the experimental ratio than exactly 4.

For any value of the radius, the electron and the positron are each moving at half the speed around their common center of mass, and each has only one fourth the kinetic energy.

For the hydrogen atom Bohr starts with his derived formula for the energy released as a free electron moves into a stable circular orbit indexed by

[32] The 1913 Bohr model did not discuss higher elements in detail and John William Nicholson was one of the first to prove in 1914 that it couldn't work for lithium, but was an attractive theory for hydrogen and ionized helium.

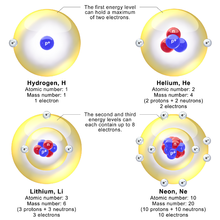

This gave a physical picture that reproduced many known atomic properties for the first time although these properties were proposed contemporarily with the identical work of chemist Charles Rugeley Bury[4][34] Bohr's partner in research during 1914 to 1916 was Walther Kossel who corrected Bohr's work to show that electrons interacted through the outer rings, and Kossel called the rings: "shells".

The shell model was able to qualitatively explain many of the mysterious properties of atoms which became codified in the late 19th century in the periodic table of the elements.

One property was the size of atoms, which could be determined approximately by measuring the viscosity of gases and density of pure crystalline solids.

The irregular filling pattern is an effect of interactions between electrons, which are not taken into account in either the Bohr or Sommerfeld models and which are difficult to calculate even in the modern treatment.

In Kossel's paper, he writes: "This leads to the conclusion that the electrons, which are added further, should be put into concentric rings or shells, on each of which ... only a certain number of electrons—namely, eight in our case—should be arranged.

The energy gained by an electron dropping from the second shell to the first gives Moseley's law for K-alpha lines, or Here, Rv = RE/h is the Rydberg constant, in terms of frequency equal to 3.28 x 1015 Hz.

For values of Z between 11 and 31 this latter relationship had been empirically derived by Moseley, in a simple (linear) plot of the square root of X-ray frequency against atomic number (however, for silver, Z = 47, the experimentally obtained screening term should be replaced by 0.4).

Still, even the most sophisticated semiclassical model fails to explain the fact that the lowest energy state is spherically symmetric – it doesn't point in any particular direction.

In modern quantum mechanics, the electron in hydrogen is a spherical cloud of probability that grows denser near the nucleus.

(However, many such coincidental agreements are found between the semiclassical vs. full quantum mechanical treatment of the atom; these include identical energy levels in the hydrogen atom and the derivation of a fine-structure constant, which arises from the relativistic Bohr–Sommerfeld model (see below) and which happens to be equal to an entirely different concept, in full modern quantum mechanics).

In the end, the model was replaced by the modern quantum-mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom, which was first given by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, using Heisenberg's matrix mechanics.

For example, up to first-order perturbations, the Bohr model and quantum mechanics make the same predictions for the spectral line splitting in the Stark effect.