Carbon nanotube

The predicted properties for SWCNTs were tantalising, but a path to synthesising them was lacking until 1993, when Iijima and Ichihashi at NEC, and Bethune and others at IBM independently discovered that co-vaporising carbon and transition metals such as iron and cobalt could specifically catalyse SWCNT formation.

These discoveries triggered research that succeeded in greatly increasing the efficiency of the catalytic production technique, and led to an explosion of work to characterise and find applications for SWCNTs.

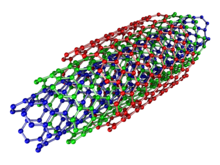

[2] A large percentage of academic and popular literature attributes the discovery of hollow, nanometre-size tubes composed of graphitic carbon to Sumio Iijima of NEC in 1991.

Using TEM images and XRD patterns, the authors suggested that their "carbon multi-layer tubular crystals" were formed by rolling graphene layers into cylinders.

Thess et al.[15] refined this catalytic method by vaporizing the carbon/transition-metal combination in a high-temperature furnace, which greatly improved the yield and purity of the SWNTs and made them widely available for characterization and application experiments.

Assigning of the carbon nanotube type was done by a combination of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), Raman spectroscopy, and density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

[26] The highest density of CNTs was achieved in 2013, grown on a conductive titanium-coated copper surface that was coated with co-catalysts cobalt and molybdenum at lower than typical temperatures of 450 °C.

The telescopic motion ability of inner shells, allowing them to act as low-friction, low-wear nanobearings and nanosprings, may make them a desirable material in nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS) .

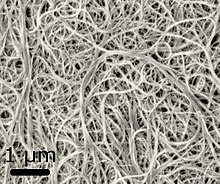

Recently, several studies have highlighted the prospect of using carbon nanotubes as building blocks to fabricate three-dimensional macroscopic (>100 nm in all three dimensions) all-carbon devices.

Lalwani et al. have reported a novel radical-initiated thermal crosslinking method to fabricate macroscopic, free-standing, porous, all-carbon scaffolds using single- and multi-walled carbon nanotubes as building blocks.

These 3D all-carbon scaffolds/architectures may be used for the fabrication of the next generation of energy storage, supercapacitors, field emission transistors, high-performance catalysis, photovoltaics, and biomedical devices, implants, and sensors.

Depositing a high density of graphene foliates along the length of aligned CNTs can significantly increase the total charge capacity per unit of nominal area as compared to other carbon nanostructures.

[67] Because of the role of the π-electron system in determining the electronic properties of graphene, doping in carbon nanotubes differs from that of bulk crystalline semiconductors from the same group of the periodic table (e.g., silicon).

Graphitic substitution of carbon atoms in the nanotube wall by boron or nitrogen dopants leads to p-type and n-type behavior, respectively, as would be expected in silicon.

A defect in metallic armchair-type tubes (which can conduct electricity) can cause the surrounding region to become semiconducting, and single monatomic vacancies induce magnetic properties.

[93] Techniques have been developed to produce nanotubes in sizeable quantities, including arc discharge, laser ablation, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and high-pressure carbon monoxide disproportionation (HiPCO).

Therefore, multiple methods have been developed to purify them including polymer-assisted,[103][104][105] density gradient ultracentrifugation (DGU),[106][107] chromatography [108][109][110] and aqueous two-phase extraction (ATPE).

Free radical grafting is a promising technique among covalent functionalization methods, in which alkyl or aryl peroxides, substituted anilines, and diazonium salts are used as the starting agents.

This can enhance the processing and manipulation of insoluble CNTs, rendering them useful for synthesizing innovative CNT nanofluids with impressive properties that are tunable for a wide range of applications.

Early scientific studies have indicated that nanoscale particles may pose a greater health risk than bulk materials due to a relative increase in surface area per unit mass.

In 2013, given that the long-term health effects have not yet been measured, NIOSH published a Current Intelligence Bulletin[148] detailing the potential hazards and recommended exposure limit for carbon nanotubes and fibers.

These include battery components, polymer composites, to improve the mechanical, thermal and electrical properties of the bulk product, and as a highly absorptive black paint.

Because of their relatively large surface area, CNTs are capable of interacting with a wide variety of therapeutic and diagnostic agents (drugs, genes, vaccines, antibodies, biosensors, etc.).

[154] In addition, CNTs have recently been used as reinforcements in implants and scaffolds due to their suitable reaction area, high elastic modulus, and load transfer capability.

Due to continuous progress in the development of detection strategies, there are numerous examples of the use of SWCNTs as highly sensitive nanosensors (even down to the single molecule level[161][162][163]) for a variety of important biomolecules.

Examples include the detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species,[164][165][166][167] neurotransmitters,[163][168][169][170][124] other small molecules,[171][172][173] lipids,[174][175] proteins,[176][177] sugars,[178][179] DNA/RNA,[180][181] enzymes[182][183] as well as bacteria.

Furthermore, the nanoscale size of SWCNTs allows dense coating of surfaces which enables chemical imaging, e.g. of cellular release processes with high spatial and temporal resolution.

[124][194] In order to avoid susceptibility of optical sensors to fluctuating ambient light, internal references such as SWCNTs that are modified to be non-responsive or stable NIR emitters[184][195] can be used.

For instance, nanotubes form a tiny portion of the material(s) in some (primarily carbon fiber) baseball bats, golf clubs, car parts, or damascus steel.

Lalwani et al. have reported a novel radical initiated thermal crosslinking method to fabricated macroscopic, free-standing, porous, all-carbon scaffolds using single- and multi-walled carbon nanotubes as building blocks.

PMCID: PMC11085746

PMCID: PMC11085746