Space elevator

[4][5][6] Decades later, in 1960, Yuri Artsutanov independently developed the concept of a "Cosmic Railway", a space elevator tethered from an orbiting satellite to an anchor on the equator, aiming to provide a safer and more efficient alternative to rockets.

[10] The space elevator concept reached America in 1975 when Jerome Pearson began researching the idea, inspired by Arthur C. Clarke's 1969 speech before Congress.

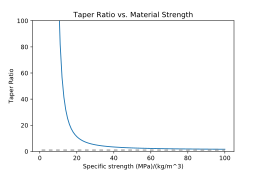

In his publication in Acta Astronautica[11], the cable would be thickest at geostationary orbit where tension is greatest, and narrowest at the tips to minimize weight per unit area.

Edwards suggested that a 100,000 km (62,000 mi) long paper-thin ribbon, utilizing a carbon nanotube composite material could solve the tether issue due to their high tensile strength and low weight [16] The proposed wide-thin ribbon-like cross-section shape instead of earlier circular cross-section concepts would increase survivability against meteoroid impacts.

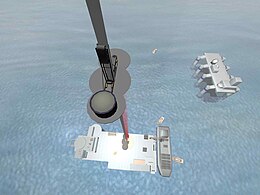

[17]: 2 The Space Elevator NIAC Phase II Final Report, in combination with the book The Space Elevator: A Revolutionary Earth-to-Space Transportation System (Edwards and Westling, 2003)[18] summarized all effort to design a space elevator[17][page needed] including deployment scenario, climber design, power delivery system, orbital debris avoidance, anchor system, surviving atomic oxygen, avoiding lightning and hurricanes by locating the anchor in the western equatorial Pacific, construction costs, construction schedule, and environmental hazards.

[4] To speed space elevator development, proponents have organized several competitions, similar to the Ansari X Prize, for relevant technologies.

Although LiftPort hopes to eventually use carbon nanotubes in the construction of a 100,000 km (62,000 mi) space elevator, this move will allow it to make money in the short term and conduct research and development into new production methods.

On 13 February 2006, the LiftPort Group announced that, earlier the same month, they had tested a mile of "space-elevator tether" made of carbon-fiber composite strings and fiberglass tape measuring 5 cm (2.0 in) wide and 1 mm (0.039 in) (approx.

[27] In April 2019, Liftport CEO Michael Laine admitted little progress has been made on the company's lofty space elevator ambitions, even after receiving more than $200,000 in seed funding.

[34] In 2013, the International Academy of Astronautics published a technological feasibility assessment which concluded that the critical capability improvement needed was the tether material, which was projected to achieve the necessary specific strength within 20 years.

[35]: 10–11, 207–208 [36][page needed] In 2014, Google X's Rapid Evaluation R&D team began the design of a Space Elevator, eventually finding that no one had yet manufactured a perfectly formed carbon nanotube strand longer than a meter.

This last conclusion is based on a potential process for manufacturing macro-scale single crystal graphene[42] with higher specific strength than carbon nanotubes.

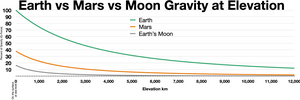

For locations in the Solar System with weaker gravity than Earth's (such as the Moon or Mars), the strength-to-density requirements for tether materials are not as problematic.

Three years later, in Robert A. Heinlein's 1982 novel Friday, the principal character mentions a disaster at the “Quito Sky Hook” and makes use of the "Nairobi Beanstalk" in the course of her travels.

In a biological version, Joan Slonczewski's 2011 novel The Highest Frontier depicts a college student ascending a space elevator constructed of self-healing cables of anthrax bacilli.

Because the counterweight, above GEO, is rotating about the Earth faster than the natural orbital speed for that altitude, it exerts a centrifugal pull on the cable and thus holds the whole system aloft.

The apparent gravitational field can be represented this way:[52]: Table 1 where At some point up the cable, the two terms (downward gravity and upward centrifugal force) are equal and opposite.

Setting actual gravity equal to centrifugal acceleration gives:[52]: p. 126 This is 35,786 km (22,236 mi) above Earth's surface, the altitude of geostationary orbit.

How the cross section area tapers from the maximum at 35,786 km (22,236 mi) to the minimum at the surface is therefore an important design factor for a space elevator cable.

Other factors considered in more detailed designs include thickening at altitudes where more space junk is present, consideration of the point stresses imposed by climbers, and the use of varied materials.

Mobile base stations would have the advantage over the earlier stationary concepts (with land-based anchors) by being able to maneuver to avoid high winds, storms, and space debris.

The opposite process would occur for descending payloads: the cable is tilted eastward, thus slightly increasing Earth's rotation speed.

Yoshio Aoki, a professor of precision machinery engineering at Nihon University and director of the Japan Space Elevator Association, suggested including a second cable and using the conductivity of carbon nanotubes to provide power.

[31] Several solutions have been proposed to act as a counterweight: Extending the cable has the advantage of some simplicity of the task and the fact that a payload that went to the end of the counterweight-cable would acquire considerable velocity relative to the Earth, allowing it to be launched into interplanetary space.

[72][73] The Earth's Moon is a potential location for a Lunar space elevator, especially as the specific strength required for the tether is low enough to use currently available materials.

[74] A far-side lunar elevator would pass through the L2 Lagrangian point and would need to be longer than on the near-side; again, the tether length depends on the chosen apex anchor mass, but it could also be made of existing engineering materials.

A space elevator using presently available engineering materials could be constructed between mutually tidally locked worlds, such as Pluto and Charon or the components of binary asteroid 90 Antiope, with no terminus disconnect, according to Francis Graham of Kent State University.

[15][79] These earlier concepts for construction require a large preexisting space-faring infrastructure to maneuver an asteroid into its needed orbit around Earth.

Earlier designs imagined the balancing mass to be another cable (with counterweight) extending upward, with the main spool remaining at the original geosynchronous orbit level.

The first 207 climbers would carry up and attach more cable to the original, increasing its cross section area and widening the initial ribbon to about 160 mm wide at its widest point.

Surface gravity is less than 3% of Earth 's