Sabkha

A sabkha (Arabic: سبخة) is a predominately coastal, supratidal mudflat or sandflat in which evaporite-saline minerals accumulate as the result of a semiarid to arid climate.

Sabkhas are gradational between land and intertidal zone within restricted coastal plains just above normal high-tide level.

[7] The origin and progression of coastal sabkha development at the southern shore of the Persian Gulf was first discussed in detail in the seminal paper by Evans et al. 1969.

[8] The coast of Abu Dhabi is locally protected from open-marine conditions by a number of peninsulas and offshore shoals and islands associated with the east–west trending Great Pearl Bank.

This lack of plant cover allows aeolian processes to interact with the phreatic surface to form unique landforms, such as sabkhas.

The resultant surfaces evolve into vast, flat, discharge areas where the process of evaporation leads to the accumulation of salts.

[9] In the khor-lagoon-sabkha model, an initial rise in sea-level floods coastal areas and creates shallow water features.

If the features silt up, or the land rises, or the sea level falls, then the trapped water evaporates, leaving a flat salt pan, or sabkha.

A sabkha may be inundated during higher than normal spring tides, after rainstorms, or when driving winds push seawater onshore to a depth of a few centimeters.

Sabkhas seaward of low outcrops of Miocene carbonate-evaporites or alluvial fans off the Oman fold and thrust belt can be as narrow as several hundred meters.

In some parts of the world, these lakes can also form in inland deserts, filled by rain or a rising water table from underground aquifers.

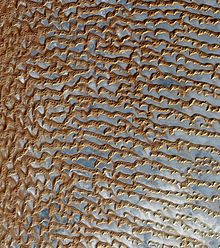

For example, large parts of the Empty Quarter in Saudi Arabia and the southern UAE consist of patterns of high drifting barchan dunes alternating with continental sabkha filled with salt flats.

However, after rains and flash-floods, the continental sabkha fill with shallow layers of water, and cannot be crossed until they dry out to form a new crust.

Halite is deposited on the surface of the sabkha and gypsum and aragonite precipitate in the subsurface[14] via capillary action from brines brought up from the water table.

[13] Thermal contraction at night and expansion during the day leads to concave polygonal pans as the edges have been upturned, in part due to growth of evaporites wedging the crack apart.

Factors enabling preservation include the progradation of the sabkha with sedimentation rates of 1 m/1000 years and the creation of Stokes surfaces.

The source of these hydrocarbons (both gas and oil) may be the microbial mats and mangrove paleosoils, found in the sabkha sequence, that have total organic carbon up to 8.2% and hydrogen indices typical of marine type II kerogens.

Modern sabkhas are present in varying form along the coasts of North Africa, Baja California, and at Shark Bay in Australia.

In addition, the extreme climatic conditions under which sabkha deposits form - such as substantial temperature fluctuations and recurrent cycles of wetting and drying - can induce instability in these soils, and some minerals that act as binding agents, or 'cements', in these soils have a high solubility, which can potentially reduce the overall structural integrity.

The precipitated minerals within the soil of these inland sabkhas depend significantly on the specific composition of the local groundwater.