Sacagawea

Sacagawea (/ˌsækədʒəˈwiːə/ SAK-ə-jə-WEE-ə or /səˌkɒɡəˈweɪə/ sə-KOG-ə-WAY-ə;[1] also spelled Sakakawea or Sacajawea; May c. 1788 – December 20, 1812)[2][3][4] was a Lemhi Shoshone woman who, in her teens, helped the Lewis and Clark Expedition in achieving their chartered mission objectives by exploring the Louisiana Territory.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association of the early 20th century adopted Sacagawea as a symbol of women's worth and independence, erecting several statues and plaques in her memory, and doing much to recount her accomplishments.

Knowing they would need to communicate with the tribal nations who lived at the headwaters of the Missouri River, they agreed to hire Toussaint Charbonneau, who claimed to speak several Native languages, and one of his wives, who spoke Shoshone.

"[b] Lewis recorded the birth of Jean Baptiste Charbonneau on February 11, 1805, noting that another of the party's interpreters administered crushed rattlesnake rattles in water to speed the delivery.

The meeting of those people was really affecting, particularly between Sah cah-gar-we-ah and an Indian woman, who had been taken prisoner at the same time with her, and who had afterwards escaped from the Minnetares and rejoined her nation.And Clark in his:[12] The Intertrepeter [sic] & Squar who were before me at Some distance danced for the joyful Sight, and She made signs to me that they were her nation ...The Shoshone agreed to barter horses and to provide guides to lead the expedition over the Rocky Mountains.

As the expedition approached the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific Coast, Sacagawea gave up her beaded belt to enable the captains to trade for a fur robe they wished to bring back to give to President Thomas Jefferson.

Lewis & my Self endeavored to purchase the roab with different articles at length we precured it for a belt of blue beeds which the Squar—wife of our interpreter Shabono wore around her waste.

[sic]When the corps reached the Pacific Ocean, all members of the expedition—including Sacagawea and Clark's enslaved servant York—voted on November 24 on the location for building their winter fort.

While traveling through what is now Franklin County, Washington, in October 1805, Clark noted that "the wife of Shabono [Charbonneau] our interpreter, we find reconciles all the Indians, as to our friendly intentions a woman with a party of men is a token of peace.

[16] As Clark traveled downriver from Fort Mandan at the end of the journey, on board the pirogue near the Ricara Village, he wrote to Charbonneau:[17] You have been a long time with me and conducted your Self in Such a manner as to gain my friendship, your woman who accompanied you that long dangerous and fatigueing rout to the Pacific Ocian and back diserved a greater reward for her attention and services on that rout than we had in our power to give her at the Mandans.

[sic]Following the expedition, Charbonneau and Sacagawea spent three years among the Hidatsa before accepting William Clark's invitation to settle in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1809.

"[21] John Luttig, a Fort Lisa clerk, recorded in his journal on December 20, 1812, that "the wife of Charbonneau, a Snake Squaw [i.e. Shoshone], died of putrid fever.

[19] In February 1813, a few months after Luttig's journal entry, 15 men were killed in a Native attack on Fort Lisa, which was then located at the mouth of the Bighorn River.

"[18] Some oral traditions relate that, rather than dying in 1812, Sacagawea left her husband Charbonneau, crossed the Great Plains, and married into a Comanche tribe.

He disliked the way Indians were treated in the missions and left to become a hotel clerk in Auburn, California, once the center of gold rush activity.

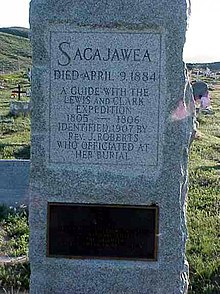

[19][25] The question of Sacagawea's burial place caught the attention of national suffragists seeking voting rights for women, according to author Raymond Wilson.

[26] Wilson notes:[26] Interest in Sacajawea peaked and controversy intensified when Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard, professor of political economy at the University of Wyoming in Laramie and an active supporter of the Nineteenth Amendment, campaigned for federal legislation to erect an edifice honoring Sacajawea's alleged death in 1884.An account of the expedition published in May 1919 noted that "A sculptor, Mr. Bruno Zimm, seeking a model for a statue of Sacagawea that was later erected at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, discovered a record of the pilot-woman's death in 1884 (when ninety-five years old) on the Shoshone Reservation, Wyoming, and her wind-swept grave.

Some of those he interviewed said that she spoke of a long journey wherein she had helped white men, and that she had a silver Jefferson peace medal of the type carried by the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

[28] According to these narratives, Porivo lived for some time at Fort Bridger in Wyoming with her sons Bazil and Baptiste, who each knew several languages, including English and French.

[31] The belief that Sacagawea lived to old age and died in Wyoming was widely disseminated in the United States through Sacajawea (1933), a biography written by Grace Raymond Hebard, based on her 30 years of research.

Critics have also questioned Hebard's work[32] because she portrayed Sacajawea in a manner described as "undeniably long on romance and short on hard evidence, suffering from a sentimentalization of Indian culture.

[35] That is, they heard a name that approximated tsakaka and wia, and interpreted it as 'bird woman', substituting their hard "g/k" pronunciation for the softer "tz/j" sound that did not exist in the Hidatsa language.

It is likely that Dye used Biddle's secondary source for the spelling, and her highly popular book made this version ubiquitous throughout the United States (previously most non-scholars had never even heard of Sacagawea).

Sacajawea was a Lemhi Shoshone not a Hidatsa.Idaho native John Rees explored the 'boat launcher' etymology in a long letter to the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs written in the 1920s.

[9] It was republished in 1970 by the Lemhi County Historical Society as a pamphlet entitled "Madame Charbonneau" and contains many of the arguments in favor of the Shoshone derivation of the name.

[40][41] Charbonneau told expedition members that his wife's name meant "Bird Woman," and in May 1805 Lewis used the Hidatsa meaning in his journal: [A] handsome river of about fifty yards in width discharged itself into the shell river… [T]his stream we called Sah-ca-gah-we-ah or bird woman's River, after our interpreter the Snake woman.Sakakawea is the official spelling of her name according to the Three Affiliated Tribes, which include the Hidatsa.

This spelling is widely used throughout North Dakota (where she is considered a state heroine), notably in the naming of Lake Sakakawea, the extensive reservoir of Garrison Dam on the Missouri River.

The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark (1902), was written by American suffragist Eva Emery Dye and published in anticipation of the expedition's centennial.

[45] The National American Woman Suffrage Association embraced her as a female hero, and numerous stories and essays about her were published in ladies' journals.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association of the early 20th century adopted her as a symbol of women's worth and independence, erecting several statues and plaques in her memory, and doing much to spread the story of her accomplishments.