Safavid Iran

[31] An Iranian dynasty rooted in the Sufi Safavid order[32] founded by sheikhs claimed by some sources to be of Kurdish[33] origin, it heavily intermarried with Turkoman,[34] Georgian,[35] Circassian,[36][37] and Pontic Greek[38] dignitaries and was Turkish-speaking and Turkified.

[29] The Safavids have also left their mark down to the present era by establishing Twelver Shīʿīsm as the state religion of Iran, as well as spreading Shīʿa Islam in major parts of the Middle East, Central Asia, Caucasus, Anatolia, the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia.

"[citation needed] At that time, the most powerful dynasty in Iran was that of the Qara Qoyunlu, the "Black Sheep", whose ruler Jahan Shah ordered Junāyd to leave Ardabil or else he would bring destruction and ruin upon the city.

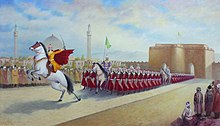

[75] Having started with just the possession of Azerbaijan, Shirvan, southern Dagestan (with its important city of Derbent), and Armenia in 1501,[76] Erzincan and Erzurum fell into his power in 1502,[77] Hamadan in 1503, Shiraz and Kerman in 1504, Diyarbakır, Najaf, and Karbala in 1507, Van in 1508, Baghdad in 1509, and Herat, as well as other parts of Khorasan, in 1510.

The tribal rivalries among the Qizilbash, which temporarily ceased before the defeat at Chaldiran, resurfaced in intense form immediately after the death of Ismāʻil, and led to ten years of civil war (930–040/1524–1533) until Shāh Tahmāsp regained control of the affairs of the state.

Soleymān agreed to permit Safavid Shi’a pilgrims to make pilgrimages to Mecca and Medina as well as tombs of imams in Iraq and Arabia on condition that the shah would abolish the taburru, the cursing of the first three Rashidun caliphs.

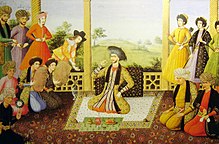

[94][95] After Humayun converted to Shiʻi Islam (under extreme duress),[94] Tahmāsp offered him military assistance to regain his territories in return for Kandahar, which controlled the overland trade route between central Iran and the Ganges.

According to Encyclopædia Iranica, for Tahmāsp, the problem circled around the military tribal elite of the empire, the Qezelbāš, who believed that physical proximity to and control of a member of the immediate Safavid family guaranteed spiritual advantages, political fortune, and material advancement.

As non-Turcoman converts to Islam, these Circassian and Georgian ḡolāmāns (also written as ghulams) were completely unrestrained by clan loyalties and kinship obligations, which was an attractive feature for a ruler like Tahmāsp whose childhood and upbringing had been deeply affected by Qezelbāš tribal politics.

[99] Although the first slave soldiers would not be organized until the reign of Abbas I, during Tahmāsp's time Caucasians would already become important members of the royal household, Harem and in the civil and military administration,[102][103] and by that becoming their way of eventually becoming an integral part of the society.

[112]The amirs demanded that she be removed, and Mahd-i Ulya was strangled in the harem in July 1579 on the ground of an alleged affair with the brother of the Crimean khan, Adil Giray,[112] who was captured during the 1578–1590 Ottoman war and held captive in the capital, Qazvin.

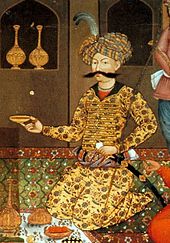

Yet over the course of ten years Abbas was able, using cautiously timed but nonetheless decisive steps, to affect a profound transformation of Safavid administration and military, throw back the foreign invaders, and preside over a flourishing of Persian art.

[134] As mentioned by the Encyclopaedia Iranica, lastly, from 1600 onwards, the Safavid statesman Allāhverdī Khan, in conjunction with Robert Sherley, undertook further reorganizations of the army, which meant among other things further dramatically increasing the number of ghulams to 25,000.

[137][138][139][140] After fully securing the region, he executed the rebellious Luarsab II of Kartli and later had the Georgian queen Ketevan, who had been sent to the shah as negotiator, tortured to death when she refused to renounce Christianity, in an act of revenge for the recalcitrance of Teimuraz.

The group crossed the Caspian Sea and spent the winter in Moscow before proceeding through Norway and Germany (where it was received by Emperor Rudolf II) to Rome, where Pope Clement VIII gave the travellers a long audience.

Eventually Abbas became frustrated with Spain, as he did with the Holy Roman Empire, which wanted him to make his over 400,000 Armenian subjects swear allegiance to the Pope but did not trouble to inform the shah when the Emperor Rudolf signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans.

At its zenith, during the long reign of Shah Abbas I, the empire's reach comprised Iran, Iraq, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, Bahrain, and parts of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Turkey.

[166][full citation needed] At the same time, the Russians led by Peter the Great attacked and conquered swaths of Safavid Iran's North Caucasian, Transcaucasian, and northern mainland territories through the Russo-Iranian War (1722–1723).

[167]\ The tribal Afghans dominated their conquered territory for seven years but were prevented from making further gains by Nader Shah, a former slave who had risen to military leadership within the Afshar tribe in Khorasan, a vassal state of the Safavids.

[176][failed verification] Shah Tahmasp introduced a change to this, when he, and the other Safavid rulers who succeeded him, sought to blur the formerly defined lines between the two linguistic groups, by taking the sons of Turkic-speaking officers into the royal household for their education in the Persian language.

According to the Encyclopædia Iranica, for Tahmasp, the background of this initiation and eventual composition that would be only finalized under Shah Abbas I, circled around the military tribal elite of the empire, the Qizilbash, who believed that physical proximity to and control of a member of the immediate Safavid family guaranteed spiritual advantages, political fortune, and material advancement.

The series of campaigns that Tahmāsp subsequently waged after realising this in the wider Caucasus between 1540 and 1554 were meant to uphold the morale and the fighting efficiency of the Qizilbash military,[178] but they brought home large numbers (over 70,000)[179] of Christian Georgian, Circassian and Armenian slaves as its main objective, and would be the basis of this third force; the new (Caucasian) layer in society.

[100] According to the Encyclopædia Iranica, this would be as well the starting point for the corps of the ḡolāmān-e ḵāṣṣa-ye-e šarifa, or royal slaves, who would dominate the Safavid military for most of the empire's length, and would form a crucial part of the third force.

As non-Turcoman converts to Islam, these Circassian and Georgian ḡolāmāns (also written as ghulams) were completely unrestrained by clan loyalties and kinship obligations, which was an attractive feature for a ruler like Tahmāsp whose childhood and upbringing had been deeply affected by Qizilbash tribal politics.

Increasingly, members of the religious class, particularly the mujtahids and the seyyeds, gained full ownership of these lands, and, according to contemporary historian Iskandar Munshi, Iran started to witness the emergence of a new and significant group of landowners.

The growth of Safavid economy was fuelled by the stability which allowed the agriculture to thrive, as well as trade, due to Iran's position between the burgeoning civilizations of Europe to its west and India and Islamic Central Asia to its east and north.

[226] In 1602, Shah Abbas I drove the Portuguese out of Bahrain, but he needed naval assistance from the newly arrived English East India Company to finally expel them from the Strait of Hormuz and regain control of this trading route.

Increased contact with distant cultures in the 17th century, especially Europe, provided a boost of inspiration to Iranian artists who adopted modeling, foreshortening, spatial recession, and the medium of oil painting (Shah Abbas II sent Muhammad Zaman to study in Rome).

By choosing the central city of Isfahan, fertilized by the Zāyande roud ("The life-giving river"), lying as an oasis of intense cultivation in the midst of a vast area of arid landscape, he both distanced his capital from any future assaults by the Ottomans and the Uzbeks, and at the same time gained more control over the Persian Gulf, which had recently become an important trading route for the Dutch and English.

The founder of the dynasty, Shah Isma'il, adopted the title of "King of Iran" (Pādišah-ī Īrān), with its implicit notion of an Iranian state stretching from Khorasan as far as Euphrates, and from the Oxus to the southern Territories of the Persian Gulf.