Camille Saint-Saëns

[6] Victor Saint-Saëns was of Norman ancestry, and his wife was from a Haute-Marne family;[n 2] their son, born in the Rue du Jardinet in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, and baptised at the nearby church of Saint-Sulpice, always considered himself a true Parisian.

[15] Stamaty required his students to play while resting their forearms on a bar situated in front of the keyboard, so that all the pianist's power came from the hands and fingers rather than the arms, which, Saint-Saëns later wrote, was good training.

[23] His organ professor was François Benoist, whom Saint-Saëns considered a mediocre organist but a first-rate teacher;[24] his pupils included Adolphe Adam, César Franck, Charles Alkan, Louis Lefébure-Wély and Georges Bizet.

[29] This work, with military fanfares and augmented brass and percussion sections, caught the mood of the times in the wake of the popular rise to power of Napoleon III and the restoration of the French Empire.

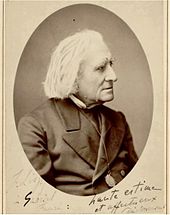

[35] Among the musicians who were quick to spot Saint-Saëns's talent were the composers Gioachino Rossini, Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt, and the influential singer Pauline Viardot, who all encouraged him in his career.

"[38] In 1861 Saint-Saëns accepted his only post as a teacher, at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse, Paris, which Louis Niedermeyer had established in 1853 to train first-rate organists and choirmasters for the churches of France.

[39] His best-known pupil, Gabriel Fauré, recalled in old age: After allowing the lessons to run over, he would go to the piano and reveal to us those works of the masters from which the rigorous classical nature of our programme of study kept us at a distance and who, moreover, in those far-off years, were scarcely known. ...

[49] While teaching at the Niedermeyer school Saint-Saëns put less of his energy into composing and performing, although an overture entitled Spartacus was crowned at a competition instituted in 1863 by the Société Sainte Cécile of Bordeaux.

[50] In 1867 his cantata Les noces de Prométhée beat more than a hundred other entries to win the composition prize of the Grande Fête Internationale in Paris, for which the jury included Auber, Berlioz, Gounod, Rossini and Giuseppe Verdi.

[n 9] The Société Nationale de Musique, with its motto, "Ars Gallica", had been established in February 1871, with Bussine as president, Saint-Saëns as vice-president and Henri Duparc, Fauré, Franck and Jules Massenet among its founder-members.

[57] As an admirer of Liszt's innovative symphonic poems, Saint-Saëns enthusiastically adopted the form; his first "poème symphonique" was Le Rouet d'Omphale (1871), premiered at a concert of the Sociéte Nationale in January 1872.

His four-act "drame lyricque", Le timbre d'argent ("The Silver Bell"), to Jules Barbier's and Michel Carré's libretto, reminiscent of the Faust legend, had been in rehearsal in 1870, but the outbreak of war halted the production.

[69] The dedicatee of the opera, Albert Libon, died three months after the premiere, leaving Saint-Saëns a large legacy "To free him from the slavery of the organ of the Madeleine and to enable him to devote himself entirely to composition".

He was not a conventional Christian, and found religious dogma increasingly irksome;[n 12] he had become tired of the clerical authorities' interference and musical insensitivity; and he wanted to be free to accept more engagements as a piano soloist in other cities.

[73] He composed a Messe de Requiem in memory of his friend, which was performed at Saint-Sulpice to mark the first anniversary of Libon's death; Charles-Marie Widor played the organ and Saint-Saëns conducted.

[63] When it was produced at Covent Garden in 1898, The Era commented that though French librettists generally "make a pretty hash of British history", this piece was "not altogether contemptible as an opera story".

[110] When a group of French musicians led by Saint-Saëns tried to organise a boycott of German music during the First World War, Fauré and Messager dissociated themselves from the idea, though the disagreement did not affect their friendship with their old teacher.

They were privately concerned that their friend was in danger of looking foolish with his excess of patriotism,[111] and his growing tendency to denounce in public the works of rising young composers, as in his condemnation of Debussy's En blanc et noir (1915): "We must at all costs bar the door of the Institut against a man capable of such atrocities; they should be put next to the cubist pictures.

His incomparable talent for orchestration enables him to give relief to ideas which would otherwise be crude and mediocre in themselves ... his works are on the one hand not frivolous enough to become popular in the widest sense, nor on the other do they take hold of the public by that sincerity and warmth of feeling which is so convincing.

In a profile of him written to mark his eightieth birthday, the critic D C Parker wrote, "That Saint-Saëns knows Rameau ... Bach and Handel, Haydn and Mozart, must be manifest to all who are familiar with his writings.

[120] The authors of the 1955 The Record Guide, Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor write that Saint-Saëns's brilliant musicianship was "instrumental in drawing the attention of French musicians to the fact that there are other forms of music besides opera.

It changes from a wistful and tense opening to a swaggering main theme, described as faintly sinister by the critic Gerald Larner, who goes on, "After a multi-stopped cadenza ... the solo violin makes a breathless sprint through the coda to the happy ending in A major".

From Meyerbeer he drew the effective use of the chorus in the action of a piece;[143] for Henry VIII he included Tudor music he had researched in London;[144] in La princesse jaune he used an oriental pentatonic scale;[120] from Wagner he derived the use of leitmotifs, which, like Massenet, he used sparingly.

[146] In a survey of recorded opera Alan Blyth writes that Saint-Saëns "certainly learned much from Handel, Gluck, Berlioz, the Verdi of Aida, and Wagner, but from these excellent models he forged his own style.

He was highly sensitive to word setting, and told the young composer Lili Boulanger that to write songs effectively musical talent was not enough: "you must study the French language in depth; it is indispensable.

[29][153] Unlike his pupil, Fauré, whose long career as a reluctant organist left no legacy of works for the instrument, Saint-Saëns published a modest number of pieces for organ solo.

[167] In the early 2020s the Centre de musique romantique française's Bru Zane label issued new recordings of Le Timbre d'argent (conducted by François-Xavier Roth, 2020), La Princesse jaune (Leo Hussain, 2021), and Phryné (Hervé Niquet, 2022).

[170][171] In its obituary notice, The Times commented: The death of M. Saint-Saëns not only deprives France of one of her most distinguished composers; it removes from the world the last representative of the great movements in music which were typical of the 19th century.

He had maintained so vigorous a vitality and kept in such close touch with present-day activities that, though it had become customary to speak of him as the doyen of French composers, it was easy to forget the place he actually took in musical chronology.

The critic Henry Colles, wrote, a few days after the composer's death: In his desire to maintain "the perfect equilibrium" we find the limitation of Saint-Saëns's appeal to the ordinary musical mind.