Salt gland

It is found in the cartilaginous fishes subclass elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, and skates), seabirds, and some reptiles.

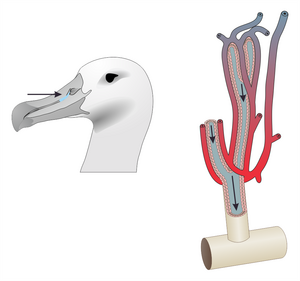

[2] Active transport via sodium–potassium pump, found on the basolateral membrane, moves salt from the blood into the gland, where it is excreted as a concentrated solution.

Salt gland activations occurs from increased osmolarity in the blood, stimulating the hypothalamic information processing, sending a signal through the parasympathetic nerve activating vasodilation, the release of hormones (acetylcholine and vasoactive intestinal peptide).

An electrical gradient is formed from the chloride ions, allowing sodium to be passed through the tight junctions of the epithelial cells into the salt gland along with minimal amounts of water.

These glands excrete the hypertonic sodium-chloride (with few other ions) by the stimulus of central and peripheral osmoreceptors and volume receptors.

The gland's function is similar to that of the kidneys, though it is much more efficient at removing salt, allowing penguins to survive without access to fresh water.

The need for salt excretion in reptiles (such as marine iguanas and sea turtles) and birds (such as petrels and albatrosses) reflects their having much less efficient kidneys than mammals.

[5] Unlike the skin of amphibians, that of reptiles and birds is impermeable to salt, preventing its release.