Sand casting

The mixture is moistened, typically with water, but sometimes with other substances, to develop the strength and plasticity of the clay and to make the aggregate suitable for molding.

Gas and steam generated during casting exit through the permeable sand or via risers,[note 1] which are added either in the pattern itself, or as separate pieces.

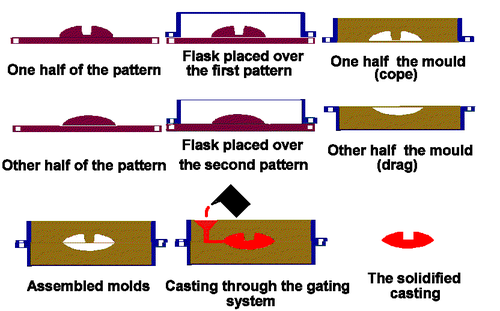

A multi-part molding box (known as a casting flask, the top and bottom halves of which are known respectively as the cope and drag) is prepared to receive the pattern.

[3] Besides replacing older methods, additive can also complement them in hybrid models, such as making a variety of AM-printed cores for a cavity derived from a traditional pattern.

Whenever possible, designs are made that avoid the use of cores, due to the additional set-up time, mass and thus greater cost.

Various heat treatments may be applied to relieve stresses from the initial cooling and to add hardness—in the case of steel or iron, by quenching in water or oil.

And when high precision is required, various machining operations (such as milling or boring) are made to finish critical areas of the casting.

A slight taper, known as draft, must be used on surfaces perpendicular to the parting line, in order to be able to remove the pattern from the mold.

The sprue and risers must be arranged to allow a proper flow of metal and gasses within the mold in order to avoid an incomplete casting.

For critical applications, or where the cost of wasted effort is a factor, non-destructive testing methods may be applied before further work is performed.

Coal, typically referred to in foundries as sea-coal, which is present at a ratio of less than 5%, partially combusts in the presence of the molten metal, leading to offgassing of organic vapors.

If necessary, a temporary plug is placed in the sand and touching the pattern in order to later form a channel into which the casting fluid can be poured.

Air-set molds are often formed with the help of a casting flask having a top and bottom part, termed the cope and drag.

Air-set molds can produce castings with smoother surfaces than coarse green sand but this method is primarily chosen when deep narrow pockets in the pattern are necessary, due to the expense of the plastic used in the process.

A heat-softened thin sheet (0.003 to 0.008 in (0.076 to 0.203 mm)) of plastic film is draped over the pattern and a vacuum is drawn (200 to 400 mmHg (27 to 53 kPa)).

[9][10] The V-process is known for not requiring a draft because the plastic film has a certain degree of lubricity and it expands slightly when the vacuum is drawn in the flask.

The main disadvantage is that the process is slower than traditional sand casting so it is only suitable for low to medium production volumes; approximately 10 to 15,000 pieces a year.

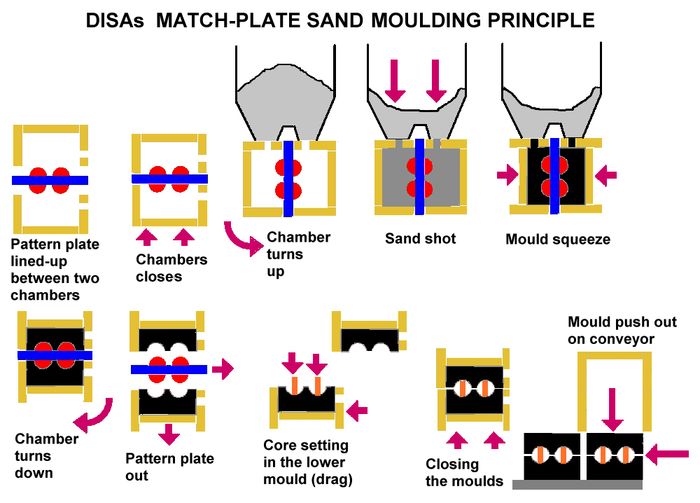

[9][10][11] With the fast development of the car and machine building industry the casting consuming areas called for steady higher productivity.

The technical and mental development however was so rapid and profound that the character of the sand casting process changed radically.

The first lines were using jolting and vibrations to pre-compact the sand in the flasks and compressed air powered pistons to compact the molds.

Although very fast, vertically parted molds are not typically used by jobbing foundries due to the specialized tooling needed to run on these machines.

However, first in the early sixties the American company Hunter Automated Machinery Corporation launched its first automatic flaskless, horizontal molding line applying the matchplate technology.

In addition, the machines are enclosed for a cleaner, quieter working environment with reduced operator exposure to safety risks or service-related problems.

Its disadvantages are very coarse grains, which result in a poor surface finish, and it is limited to dry sand molding.

The disadvantage is that its high strength leads to shakeout difficulties and possibly hot tears (probably due to quartz inversion[citation needed]) in the casting.

Additives are added to the molding components to improve: surface finish, dry strength, refractoriness, and "cushioning properties".

Up to 5% of reducing agents, such as coal powder, pitch, creosote, and fuel oil, may be added to the molding material to prevent wetting (prevention of liquid metal sticking to sand particles, thus leaving them on the casting surface), improve surface finish, decrease metal penetration, and burn-on defects.

These additives achieve this by creating gases at the surface of the mold cavity, which prevent the liquid metal from adhering to the sand.

These materials are beneficial because burn-off when the metal is poured creates tiny voids in the mold, allowing the sand particles to expand.

[23] Up to 2% of iron oxide powder can be used to prevent mold cracking and metal penetration, essentially improving refractoriness.