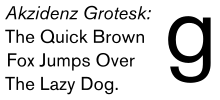

Sans-serif

For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into these major groups: § Grotesque, § Neo-grotesque, § Geometric, § Humanist, and § Other or mixed.

Influenced by Didone serif typefaces of the period and sign painting traditions, these were often quite solid, bold designs suitable for headlines and advertisements.

[10][11][12][13] According to Monotype, the term "grotesque" originates from Italian: grottesco, meaning "belonging to the cave" due to their simple geometric appearance.

[14] The term arose because of adverse comparisons that were drawn with the more ornate Modern Serif and Roman typefaces that were the norm at the time.

Similar to grotesque typefaces, neo-grotesques often feature capitals of uniform width and a quite 'folded-up' design, in which strokes (for example on the 'c') are curved all the way round to end on a perfect horizontal or vertical.

[c] Notable geometric types of the period include Kabel, Semplicità, Bernhard Gothic, Nobel and Metro; more recent designs in the style include ITC Avant Garde, Brandon Grotesque, Gotham, Avenir, Product Sans, HarmonyOS Sans and Century Gothic.

Many geometric sans-serif alphabets of the period, such as those authored by the Bauhaus art school (1919–1933) and modernist poster artists, were hand-lettered and not cut into metal type at the time.

These include most popularly Hermann Zapf's Optima (1958), a typeface expressly designed to be suitable for both display and body text.

Sans-serif typefaces intended for signage, such as Transport and Tern (both used on road signs), may have unusual features to enhance legibility and differentiate characters, such as a lower-case 'L' with a curl or 'i' with serif under the dot.

[35] Letters without serifs have been common in writing across history, for example in casual, non-monumental epigraphy of the classical period.

The earliest printing typefaces which omitted serifs were not intended to render contemporary texts, but to represent inscriptions in Ancient Greek and Etruscan.

[38][39][40] Towards the end of the eighteenth century neoclassicism led to architects increasingly incorporating ancient Greek and Roman designs in contemporary structures.

[43] These were then copied by other artists, and in London sans-serif capitals became popular for advertising, apparently because of the "astonishing" effect the unusual style had on the public.

The lettering style apparently became referred to as "old Roman" or "Egyptian" characters, referencing the classical past and a contemporary interest in Ancient Egypt and its blocky, geometric architecture.

The inappropriateness of the name was not lost on the poet Robert Southey, in his satirical Letters from England written in the character of a Spanish aristocrat.

They are simply the common characters, deprived of all beauty and all proportion by having all the strokes of equal thickness, so that those which should be thin look as if they had the elephantiasis.

"[53][43] Similarly, the painter Joseph Farington wrote in his diary on 13 September 1805 of seeing a memorial[h] engraved "in what is called Egyptian Characters".

This was arrestingly bold and highly condensed, quite unlike the classical proportions of Caslon's design, but very suitable for poster typography and similar in aesthetic effect to the (generally wider) slab serif and "fat faces" of the period.

The term "grotesque" comes from the Italian word for cave, and was often used to describe Roman decorative styles found by excavation, but had long become applied in the modern sense for objects that appeared "malformed or monstrous".

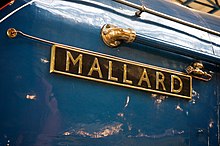

[40][72] Sans-serif lettering and typefaces were popular due to their clarity and legibility at distance in advertising and display use, when printed very large or small.

The first use of sans-serif as a running text has been proposed to be the short booklet Feste des Lebens und der Kunst: eine Betrachtung des Theaters als höchsten Kultursymbols (Celebration of Life and Art: A Consideration of the Theater as the Highest Symbol of a Culture),[73] by Peter Behrens, in 1900.

[74] Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sans-serif types were viewed with suspicion by many printers, especially those of fine book printing, as being fit only for advertisements (if that), and to this day[when?]

In 1922, master printer Daniel Berkeley Updike described sans-serif typefaces as having "no place in any artistically respectable composing-room.

While he disliked sans-serif typefaces in general, the American printer J. L. Frazier wrote of Copperplate Gothic in 1925 that "a certain dignity of effect accompanies ... due to the absence of anything in the way of frills", making it a popular choice for the stationery of professionals such as lawyers and doctors.

[79] As Updike's comments suggest, the new, more constructed humanist and geometric sans-serif designs were viewed as increasingly respectable, and were shrewdly marketed in Europe and America as embodying classic proportions (with influences of Roman capitals) while presenting a spare, modern image.

[89][90][91] Writing in The Typography of Press Advertisement (1956), printer Kenneth Day commented that Stephenson Blake's eccentric Grotesque series had returned to popularity for having "a personality sometimes lacking in the condensed forms of the contemporary sans cuttings of the last thirty years.