Saturnalia

In Roman mythology, Saturn was an agricultural deity who was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labour in a state of innocence.

[6] The ancient Roman historian Justinus credits Saturn with being a historical king of the pre-Roman inhabitants of Italy: "The first inhabitants of Italy were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal."

[8] The Saturnalia was the dramatic setting of the multivolume work of that name by Macrobius, a Latin writer from late antiquity who is the major source for information about the holiday.

Macrobius describes the reign of Justinus's "king Saturn" as "a time of great happiness, both on account of the universal plenty that prevailed and because as yet there was no division into bond and free – as one may gather from the complete license enjoyed by slaves at the Saturnalia.

[10] In one of the interpretations in Macrobius's work, Saturnalia is a festival of light leading to the winter solstice, with the abundant presence of candles symbolizing the quest for knowledge and truth.

[11] The renewal of light and the coming of the new year was celebrated in the later Roman Empire at the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the "Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun", on 25 December.

[12] The popularity of Saturnalia continued into the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, and as the Roman Empire came under Christian rule, many of its customs were recast into or at least influenced the seasonal celebrations surrounding Christmas and the New Year.

[13][14][15] Saturnalia underwent a major reform in 217 BC, after the Battle of Lake Trasimene, when the Romans suffered one of their most crushing defeats by Carthage during the Second Punic War.

Palmer has argued that the introduction of new rites at this time was in part an effort to appease Ba'al Hammon, the Carthaginian god who was regarded as the counterpart of the Roman Saturn and Greek Cronus.

[27] Following the sacrifice the Roman Senate arranged a lectisternium, a ritual of Greek origin that typically involved placing a deity's image on a sumptuous couch, as if he were present and actively participating in the festivities.

[35] Saturn's chthonic nature connected him to the underworld and its ruler Dīs Pater, the Roman equivalent of Greek Plouton (Pluto in Latin) who was also a god of hidden wealth.

For at this festival, in houses that keep to proper religious usage, they first of all honor the slaves with a dinner prepared as if for the master; and only afterwards is the table set again for the head of the household.

[47] The toga, the characteristic garment of the male Roman citizen, was set aside in favor of the Greek synthesis, colourful "dinner clothes" otherwise considered in poor taste for daytime wear.

[48] Romans of citizen status normally went about bare-headed, but for the Saturnalia donned the pilleus, the conical felt cap that was the usual mark of a freedman.

[52][53] No theatrical events are mentioned in connection with the festivities, but the classicist Erich Segal saw Roman comedy, with its cast of impudent, free-wheeling slaves and libertine seniors, as imbued with the Saturnalian spirit.

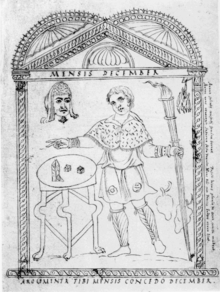

On the Calendar of Philocalus, the Saturnalia is represented by a man wearing a fur-trimmed coat next to a table with dice, and a caption reading: "Now you have license, slave, to game with your master.

Loose reins are given to public dissipation; everywhere you may hear the sound of great preparations, as if there were some real difference between the days devoted to Saturn and those for transacting business. ...

Pliny describes a secluded suite of rooms in his Laurentine villa, which he used as a retreat: "... especially during the Saturnalia when the rest of the house is noisy with the licence of the holiday and festive cries.

[62] In his many poems about the Saturnalia, Martial names both expensive and quite cheap gifts, including writing tablets, dice, knucklebones, moneyboxes, combs, toothpicks, a hat, a hunting knife, an axe, various lamps, balls, perfumes, pipes, a pig, a sausage, a parrot, tables, cups, spoons, items of clothing, statues, masks, books, and pets.

Art and literature under Augustus celebrated his reign as a new Golden Age, but the Saturnalia makes a mockery of a world in which law is determined by one man and the traditional social and political networks are reduced to the power of the emperor over his subjects.

[73] The phrase io Saturnalia was the characteristic shout or salutation of the festival, originally commencing after the public banquet on the single day of 17 December.

The Temple of Saturn housed the state treasury (aerarium Saturni) and was the administrative headquarters of the quaestors, the public officials whose duties included oversight of the mint.

As the Augustan poet Virgil described it: "[H]e gathered together the unruly race [of fauns and nymphs] scattered over mountain heights, and gave them laws ....

[103] As William Warde Fowler notes: "[Saturnalia] has left its traces and found its parallels in great numbers of medieval and modern customs, occurring about the time of the winter solstice.

[107][108] Some speculate that the date was chosen to create a Christian replacement or alternative to Saturnalia[105] and the birthday festival of Sol Invictus, held on 25 December.

[107] As a result of the close proximity of dates, many Christians in western Europe continued to celebrate traditional Saturnalia customs in association with Christmas and the surrounding holidays.

[110][14] In medieval France and Switzerland, a boy would be elected "bishop for a day" on 28 December (the Feast of the Holy Innocents)[110][14] and would issue decrees much like the Saturnalicius princeps.

[111] This custom was common across western Europe, but varied considerably by region;[111] in some places, the boy bishop's orders could become quite rowdy and unrestrained,[111] but, in others, his power was only ceremonial.

[111] In some parts of France, during the boy bishop's tenure, the actual clergy would wear masks or dress in women's clothing, a reversal of roles in line with the traditional character of Saturnalia.

[14] During the late medieval period and early Renaissance, many towns in England elected a "Lord of Misrule" at Christmas time to preside over the Feast of Fools.