Savannah Protest Movement

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, African Americans in Savannah were subject to Jim Crow laws that enforced a strict system of racial segregation whereby they were not allowed to use many of the same facilities used by white people.

On March 16, 1960, the movement began with a series of sit-ins conducted by several dozen student activists at segregated lunch counters throughout downtown Savannah, resulting in the arrest of three protestors at Levy's Department Store.

By mid-1963, Williams, who by this time had become affiliated with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), began to hold nighttime marches that saw hundreds of arrests and an instance of rioting that resulted in the burning of at least one building and the mobilization of the Georgia National Guard.

[5] However, during the Interwar period, violent opposition from white Americans, including multiple lynchings, as well as the Great Depression, seriously hurt these organizations' efforts and led to the closure of many local chapters.

[15] According to historian Stephen Tuck, "The emergence of small pockets of relatively prosperous black Georgians in cities, therefore, provided the environment from which civil rights leadership could spring".

[21] Some of these electoral reforms were implemented by Georgia Governor Ellis Arnall, a political moderate who had beaten incumbent Eugene Talmadge in the 1942 election thanks to support from white liberals.

[14] Around this same time, activists in the state, especially consisting of black women, began to organize voter registration drives and pushed for the election of moderate politicians at the local level.

[34] Gilbert also led the drive to establish a YMCA on West Broad Street in the 1940s[31] After the war, the chapter under his leadership supported the Congress of Industrial Organizations's Operation Dixie, which aimed to unionize African American workers at the city's shipyard.

[32] Similar instances of KKK violence occurred in the 1946 election, spurred by candidate and former Governor Talmadge, who used a little-known provision in the Official Code of Georgia Annotated to effectively disenfranchise many African Americans.

[45][46][47] Williams believed that his hiring had been an example of tokenism, and this, coupled with an experience where one of his children was denied service at a lunch counter in the city, spurred him to become an activist for civil rights.

[42] Under Law's administration, the NAACP chapter in Savannah continued to grow, with historian Clare Russell stating that this was due in part to "the lack of overt racial violence which meant that they could organize in relatively security".

[2] These initial protests in Greensboro sparked the larger sit-in movement that saw activists in many cities throughout the American South employ similar nonviolent practices to integrate segregated spaces, such as lunch counters, stores, and public facilities.

[58] At the Azalea Room, a lunch counter inside the Levy's Department Store,[49][29] Carolyn Quilloin, Joan Tyson, and Ernest Robinson were arrested after they continued to try to order after the owner demanded that they leave.

[56] In addition to this, they also demanded the hiring of black workers at levels above menial positions, the desegregation of public drinking fountains and restrooms, and the use of courtesy titles, such as Mr., Mrs., and Miss, instead of simply "boy" or "girl",[55] when referring to African Americans.

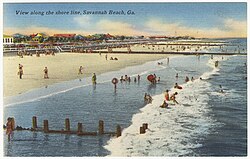

[65] Protestors, which included student activist Benjamin Van Clarke[note 4] and future Georgia House of Representatives member Edna Jackson,[69][70] swam for about 90 minutes before police put an end to the protest and arrested 11 people.

[65] On August 21, student activists affiliated with the NAACP conducted the city's first "kneel-ins", modeled after similar events in Atlanta,[57] when they visited ten white churches.

[66] A lawsuit that rose to the Supreme Court of the United States eventually overturned the charges against the kids, which carried a fine of $100 ($916 in 2021) and five months in prison,[56] as they were ruled unconstitutional.

[77] By the end of 1960, thanks in large part to the CCCV's efforts, 57 percent of the eligible black citizens of Savannah were registered to vote, a higher percentage than among the city's white population.

[52] Van Clarke would later serve as the head of the CCCV's youth division and organized as many as three marches per day, including one where protestors dressed in black and carried a casket in a mock funeral for segregation.

[83] On the other side of the protests, segregationists began a counter-boycott of stores that had already desegregated,[84] and protestors continued to face the threat of physical violence, as evidenced by a March 15 report in The Atlanta Constitution about an activist who was assaulted by a group of white youths during a sit-in at Woolworth's.

[85] Also, in July 1961,[86] Law was fired from his job with the postal service due to his civil rights activism, though he was reinstated following pushback against his termination from national NAACP leaders and United States President John F.

[56] Mayor Maclean assembled a biracial committee that agreed to several of the protestors' demands, including a commitment to hire black people to higher ranking positions and the use of courtesy titles.

[76] Additionally, the city government revoked an ordinance mandating segregated lunch counters and also desegregated many public facilities, including buses, golf courses, movie theaters, and restaurants.

[54][76] However, targeted protests still continued against institutions in the city that remained segregated,[66] such as parks, restaurants at the local airport and train station, and the Savannah Fire Department.

[74] This primarily stemmed from Williams's general dissatisfaction with the NAACP leadership's advocacy for more legislative means of achieving civil rights as opposed to more direct forms of protest.

[7] Additionally, during his lunch breaks, Williams would often give speeches from atop a boulder monument to Tomochichi at Wright Square, in front of the city's federal courthouse.

[94] After this, the remaining activists, led by Williams and Van Clarke, gathered outside the local jail to protest the arrests, during which time city and state law enforcement officers used tear gas to disperse the crowds.

[96] During the two-hour fight, police used tear gas and high-powered water hoses to disperse the crowds and beat several protestors with clubs, leading to multiple injuries.

[110] To this end, several sources have noted that local leadership turned down an offer by King to come to Savannah to participate in the protest, believing that the movement was making good progress without him.

[67] In 1962, Law, L. Scott Stell (chair of the NAACP's education board), and, several dozens black families filed a lawsuit against the city of Savannah in an attempt to force them to integrate.