Immune electron microscopy

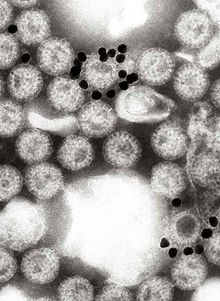

When used in immune electron microscopy, negative staining implants a small particle into the specimen, better resolving structures within it.

Some complications can arise during the preparation steps necessary to create the thin sections, including chemical fixation and embedding (usually in plastic).

Researchers have invented and utilized specific processes to circumvent these issues and preserve the interaction between the antigen and antibodies.

[5] During successful experiments, immune electron microscopy can accurately locate proteins and strengthen comprehension of the relationship between structure and function.

[3] EM fixation and embedment protocols strongly affect the immune complexing outcomes: many fixation and processing procedures of electron microscopy such as the dehydration series leading to polymerization in plastic Epon, or glutaraldehyde-formaldehyde crosslinking of proteins, do not allow binding of an antibody to its former target.

In one paper it was shown that the maintenance of active binding sites, through a gentle EM fixation and embedment procedure, revealed that cytoplasmic transport previously believed to occur via microvesicles were actually a preparation artifact, arising from a peroxidase-labelled antibody used before fixation: direct immunogold labeling in Lowicryl EM sections showed cytoplasmic transport without vesicles in ovarian tissues.

In 1931, Ernst Ruska (1986 Nobel Prize award winner) and Max Knoll created the first electron microscope.

At this time, resolution was much poorer due to a lack of additional contrast and poor quality microscopes of the day.

[4] Transmission electron microscopy successfully provides general information about structure but struggles to differentiate more detailed parts of a virus or cell.

This damage can be associated with slower nerve impulses, resulting in an extensive range of cognitive and physical issues.

In this case, scientists discovered insufficient anchoring fibrils in the basement membrane, which caused the skin to be more fragile.

In both instances, scientists identified a specific antigen to target in order to use immune electron microscopy to discover and learn more about these diseases.

Even in the patients where immunofluorescence microscopy yielded the correct results, researchers still believed confirmation was needed.