Complex number

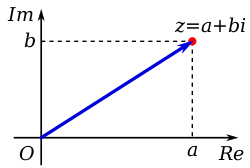

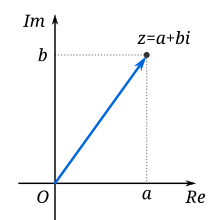

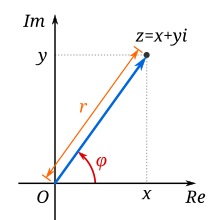

[13][14] The argument of z (sometimes called the "phase" φ)[7] is the angle of the radius Oz with the positive real axis, and is written as arg z, expressed in radians in this article.

[15] The argument can be computed from the rectangular form x + yi by means of the arctan (inverse tangent) function.

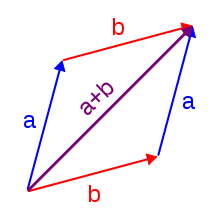

In other words, the absolute values are multiplied and the arguments are added to yield the polar form of the product.

The fundamental theorem of algebra, of Carl Friedrich Gauss and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, states that for any complex numbers (called coefficients) a0, ..., an, the equation

The rules for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and root extraction of complex numbers were developed by the Italian mathematician Rafael Bombelli.

[25] The earliest fleeting reference to square roots of negative numbers can perhaps be said to occur in the work of the Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria in the 1st century AD, where in his Stereometrica he considered, apparently in error, the volume of an impossible frustum of a pyramid to arrive at the term

[27] The impetus to study complex numbers as a topic in itself first arose in the 16th century when algebraic solutions for the roots of cubic and quartic polynomials were discovered by Italian mathematicians (Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia and Gerolamo Cardano).

It was soon realized (but proved much later)[28] that these formulas, even if one were interested only in real solutions, sometimes required the manipulation of square roots of negative numbers.

In fact, it was proved later that the use of complex numbers is unavoidable when all three roots are real and distinct.

[c] However, the general formula can still be used in this case, with some care to deal with the ambiguity resulting from the existence of three cubic roots for nonzero complex numbers.

Rafael Bombelli was the first to address explicitly these seemingly paradoxical solutions of cubic equations and developed the rules for complex arithmetic, trying to resolve these issues.

[... quelquefois seulement imaginaires c'est-à-dire que l'on peut toujours en imaginer autant que j'ai dit en chaque équation, mais qu'il n'y a quelquefois aucune quantité qui corresponde à celle qu'on imagine.

In 1806 Jean-Robert Argand independently issued a pamphlet on complex numbers and provided a rigorous proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra.

[35] Carl Friedrich Gauss had earlier published an essentially topological proof of the theorem in 1797 but expressed his doubts at the time about "the true metaphysics of the square root of −1".

[36] It was not until 1831 that he overcame these doubts and published his treatise on complex numbers as points in the plane,[37] largely establishing modern notation and terminology:[38] If one formerly contemplated this subject from a false point of view and therefore found a mysterious darkness, this is in large part attributable to clumsy terminology.

positive, negative, or imaginary (or even impossible) units, but instead, say, direct, inverse, or lateral units, then there could scarcely have been talk of such darkness.In the beginning of the 19th century, other mathematicians discovered independently the geometrical representation of the complex numbers: Buée,[39][40] Mourey,[41] Warren,[42][43][44] Français and his brother, Bellavitis.

Hardy remarked that Gauss was the first mathematician to use complex numbers in "a really confident and scientific way" although mathematicians such as Norwegian Niels Henrik Abel and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi were necessarily using them routinely before Gauss published his 1831 treatise.

Later classical writers on the general theory include Richard Dedekind, Otto Hölder, Felix Klein, Henri Poincaré, Hermann Schwarz, Karl Weierstrass and many others.

Important work (including a systematization) in complex multivariate calculus has been started at beginning of the 20th century.

For the other trigonometric and hyperbolic functions, such as tangent, things are slightly more complicated, as the defining series do not converge for all complex values.

Therefore, one must define them either in terms of sine, cosine and exponential, or, equivalently, by using the method of analytic continuation.

Complex numbers have applications in many scientific areas, including signal processing, control theory, electromagnetism, fluid dynamics, quantum mechanics, cartography, and vibration analysis.

In the network analysis of electrical circuits, the complex conjugate is used in finding the equivalent impedance when the maximum power transfer theorem is looked for.

Marden's theorem says that the solutions of this equation are the complex numbers denoting the locations of the two foci of the Steiner inellipse.

In this way, algebraic methods can be used to study geometric questions and vice versa.

In applied fields, complex numbers are often used to compute certain real-valued improper integrals, by means of complex-valued functions.

For a sine wave of a given frequency, the absolute value |z| of the corresponding z is the amplitude and the argument arg z is the phase.

where ω represents the angular frequency and the complex number A encodes the phase and amplitude as explained above.

The treatment of resistors, capacitors, and inductors can then be unified by introducing imaginary, frequency-dependent resistances for the latter two and combining all three in a single complex number called the impedance.

(This approach is no longer standard in classical relativity, but is used in an essential way in quantum field theory.)