Science and the Catholic Church

[2] From ancient times, Christian emphasis on practical charity gave rise to the development of systematic nursing and hospitals and the Church remains the single largest private provider of medical care and research facilities in the world.

[3] Following the Fall of Rome, monasteries and convents remained bastions of scholarship in Western Europe and clergymen were the leading scholars of the age – studying nature, mathematics, and the motion of the stars (largely for religious purposes).

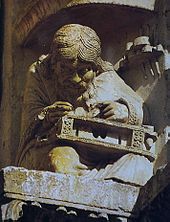

[4] During the Middle Ages, the Church founded Europe's first universities, producing scholars like Robert Grosseteste, Albert the Great, Roger Bacon, and Thomas Aquinas, who helped establish the scientific method.

[7] The Society of Jesus has been particularly active, notably in astronomy; the Papacy and the Jesuits initially promoted the observations and studies of Galileo Galilei, until the latter was put on trial and forced to recant by the Roman inquisition.

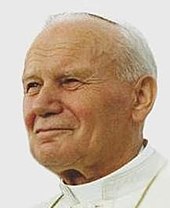

[13] Pope John Paul II expressed the Catholic Church's position on faith and reason in the encyclical Fides et Ratio, describing them as "two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth".

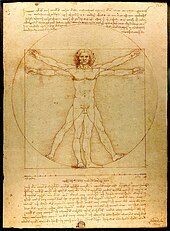

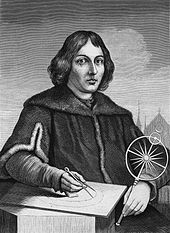

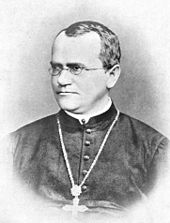

"[15] Scientific fields with important foundational contributions from Catholic scientists include: physics (Galileo) despite his trial and conviction in 1633 for publishing a treatise on his observation that the earth revolves around the sun, which banned his writings and made him spend the remainder of his life under house arrest, acoustics (Mersenne), mineralogy (Agricola), modern chemistry (Lavoisier), modern anatomy (Vesalius), stratigraphy (Steno), bacteriology (Kircher and Pasteur), genetics (Mendel), analytical geometry (Descartes), heliocentric cosmology (Copernicus), atomic theory (Boscovich), and the Big Bang Theory on the origins of the universe (Lemaître).

[47] Historian John L. Heilbron states, "the Roman Catholic Church gave more financial and social support to the study of astronomy for over six centuries, from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment, than any other, and probably all, other Institutions.

[49] In the 4th century, due to perceived problems with the Hebrew calendar's leap month system, the Council of Nicaea prescribed that Easter would fall on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the vernal equinox.

...Therefore with the utmost earnestness I entreat you, most learned sir, unless I inconvenience you, to communicate this discovery of yours to scholars, and at the earliest possible moment to send me your writings on the sphere of the universe together with the tables and whatever else you have that is relevant to this subject.

[65] He also noted that the Master of the Sacred Palace (i.e., the Catholic Church's chief censor), Bartolomeo Spina, a friend and fellow Dominican, had planned to condemn De revolutionibus but had been prevented from doing so by his illness and death.

Galileo was ordered not to support Copernican theory in 1616, but in 1632, after receiving permission from a new Pope (Urban VIII) to address the subject indirectly through a dialogue, he fell foul of the Pontiff by treating the Church's views unfavorably, assigning them to a character named Simplicio— suspiciously similar to the Italian word for "simple".

The leading Jesuit Theologian Cardinal Robert Bellarmine agreed this would be an appropriate response to a true demonstration that the Sun was at the center of the universe, but cautioned that the existing materials upon which Galileo relied did not yet constitute an established truth.

William René Shea [es] believes that "a check on anyone spreading novel ideas was in any case a routine matter in Rome during the Counter Reformation, and Galileo probably never heard that his name had cropped up at a meeting of the cardinal inquisitors.

[77] However, Galileo frequently cited the Bible and utilised theological reasoning in his writings, which worried papal censors that "it might give the impression that astronomers wanted to conquer a domain that belonged to theologians."

[99] Galileo was supported by several Catholic figures such as Monsignor Piero Dini, Carmelite Paolo Antonio Foscarini, and a Dominican Tommaso Campanella; his trial in 1633 made him gain sympathy from more clergy like Ascanio II Piccolomini and Fulgenzio Micanzio.

Despite discussing the motion of Earth and endorsing Copernican theory, Galileo did not suffer any harm from the Inquisition for publishing this book, even though it reached Rome's bookstores in January 1639, and all available copies were quickly sold.

[95] Finocchiaro states that many contemporary physicists objected to Galileo's theory as it lacked proof, which also affected the church's decision;[104] Copernicus' argument was a hypothetical one regarding what phenomena would occur if Earth was in motion.

[100] William René Shea [es] argues that Galileo attracted the interest of the inquisition by getting involved in theological matters - prior to 1616, several contradicting astronomical theories were permitted as they were treated as "tools for calculation".

[112] In 1939 Pope Pius XII, in his first speech to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, within a few months of his election to the papacy, described Galileo as being among the "most audacious heroes of research ... not afraid of the stumbling blocks and the risks on the way, nor fearful of the funereal monuments.

"[114] On 15 February 1990, in a speech delivered at the Sapienza University of Rome,[115] Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) cited some current views on the Galileo affair as forming what he called "a symptomatic case that permits us to see how deep the self-doubt of the modern age, of science and technology, goes today.

In 1961, seven years after Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA, Christian Henry Morris and John C. Witcomb[126] published The Genesis Flood, which argued that there is scientific support for the bible creation story.

[127] This updated an earlier pronouncement by Pope Pius XII in the 1950 encyclical Humani generis that accepted evolution as a possibility (as opposed to a probability) and a legitimate field of study to investigate the origins of the human body – though it was stressed that "the Catholic faith obliges us to hold that souls are immediately created by God.

[153] The church recognized that there had been a drift and that the date of Easter no longer seemed to align with heaven which created an urgent need to understand the movement of the Sun and Earth so that the calendar conflicts could be resolved.

[160] By interpreting the word orbit in both a geometric sense and in a way that could apply to the Sun or the Earth, Catholic scientists like Cassini could create enough distance from Galileo's theory to operate without condemnation from the church.

Schall, recognizing the importance of elaborate state rituals in China, offered the calendar to the Emperor in a complex ceremony involving music, parades, and signs of submission like kneeling and kowtowing.

"[113] In the 1950 encyclical Humani generis, Pius XII accepted evolution as a possibility (as opposed to a probability) and a legitimate field of study to investigate the origins of the human body – though it was stressed that "the Catholic faith obliges us to hold that souls are immediately created by God.

"[191] With the substantial increase in the proliferation and usage of large language models such as ChatGPT, Pope Francis expressed concerns about a "technocratic" future and transparency in the development of further artificial intelligence technologies at the 2024 G7 summit in 2024.

Yet the position which Pius XII defined in 1950, delinking the creation of body and soul, was confirmed by Pope John Paul II, who highlighted additional facts supporting the theory of evolution half a century later.

In his spiritual testament, Pope Benedict XVI said:[190] The scientists/historians John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White were the most influential exponents of the conflict thesis between the Catholic Church and science.

More recently, Thomas E. Woods, Jr., asserts that, despite the widely held conception of the Catholic Church as being anti-science, this conventional wisdom has been the subject of "drastic revision" by historians of science over the last 50 years.