Science in the Age of Enlightenment

Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favour of the development of free speech and thought.

Philosophes introduced the public to many scientific theories, most notably through the Encyclopédie and the popularization of Newtonianism by Voltaire as well as by Émilie du Châtelet, the French translator of Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

On the one hand, the University of Cambridge began teaching Newtonianism early in the Enlightenment, but failed to become a central force behind the advancement of science.

[15] In the 17th century, the Netherlands had played a significant role in the advancement of the sciences, including Isaac Beeckman's mechanical philosophy and Christiaan Huygens' work on the calculus and in astronomy.

Around the start of the 18th century, the Academia Scientiarum Imperialis (1724) in St. Petersburg, and the Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien (Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) (1739) were created.

Following this initial period of growth, societies were founded between 1752 and 1785 in Barcelona, Brussels, Dublin, Edinburgh, Göttingen, Mannheim, Munich, Padua and Turin.

For example, the Royal Society depended on contributions from its members, which excluded a wide range of artisans and mathematicians on account of the expense.

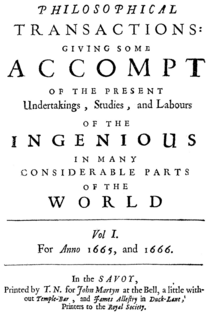

Some eminent examples include Johann Ernst Immanuel Walch's Der Naturforscher (The Natural Investigator) (1725–1778), Journal des sçavans (1665–1792), the Jesuit Mémoires de Trévoux (1701–1779), and Leibniz's Acta Eruditorum (Reports/Acts of the Scholars) (1682–1782).

[31] While the journals of the academies primarily published scientific papers, independent periodicals were a mix of reviews, abstracts, translations of foreign texts, and sometimes derivative, reprinted materials.

With a wider audience and ever increasing publication material, specialized journals such as Curtis' Botanical Magazine (1787) and the Annals de Chimie (1789) reflect the growing division between scientific disciplines in the Enlightenment era.

Published in 1704, the Lexicon technicum was the first book to be written in English that took a methodical approach to describing mathematics and commercial arithmetic along with the physical sciences and navigation.

The Marperger Curieuses Natur-, Kunst-, Berg-, Gewerkund Handlungs-Lexicon (1712) explained terms that usefully described the trades and scientific and commercial education.

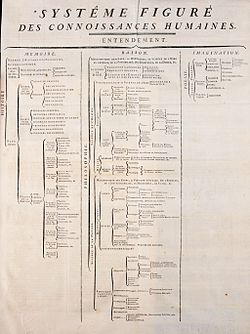

[41] However, the prime example of reference works that systematized scientific knowledge in the age of Enlightenment were universal encyclopedias rather than technical dictionaries.

The Enlightenment's desacrilization of religion was pronounced in the tree's design, particularly where theology accounted for a peripheral branch, with black magic as a close neighbour.

An increasingly literate population seeking knowledge and education in both the arts and the sciences drove the expansion of print culture and the dissemination of scientific learning.

[53] Public lecture courses offered some scientists who were unaffiliated with official organizations a forum to transmit scientific knowledge, at times even their own ideas, and the opportunity to carve out a reputation and, in some instances, a living.

Sir Isaac Newton's celebrated Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica was published in Latin and remained inaccessible to readers without education in the classics until Enlightenment writers began to translate and analyze the text in the vernacular.

[61] Émilie du Châtelet's translation of the Principia, published after her death in 1756, also helped to spread Newton's theories beyond scientific academies and the university.

The publication of Bernard de Fontenelle's Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds (1686) marked the first significant work that expressed scientific theory and knowledge expressly for the laity, in the vernacular, and with the entertainment of readers in mind.

[63] These popular works were written in a discursive style, which was laid out much more clearly for the reader than the complicated articles, treatises, and books published by the academies and scientists.

"[64] Francesco Algarotti, writing for a growing female audience, published Il Newtonianism per le dame, which was a tremendously popular work and was translated from Italian into English by Elizabeth Carter.

Extant records of subscribers show that women from a wide range of social standings purchased the book, indicating the growing number of scientifically inclined female readers among the middling class.

Other antiscience writers, including William Blake, chastised scientists for attempting to use physics, mechanics and mathematics to simplify the complexities of the universe, particularly in relation to God.

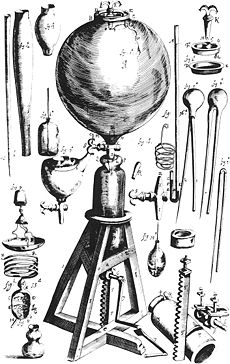

[69] A consequence of the exclusion of women from societies and universities that prevented much independent research was their inability to access scientific instruments, such as the microscope.

To be pleasing in his sight, to win his respect and love, to train him in childhood, to tend him in manhood, to counsel and console, to make his life pleasant and happy, these are the duties of woman for all time, and this is what she should be taught while she is young.

Her personal relationship with Empress Catherine the Great (r. 1762–1796) allowed her to obtain the position, which marked in history the first appointment of a woman to the directorship of a scientific academy.

Aside from assisting in Lavoisier's laboratory research, she was responsible for translating a number of English texts into French for her husband's work on the new chemistry.

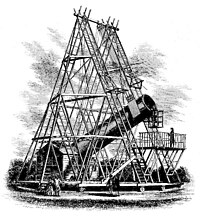

[77] James Bradley, while attempting to document stellar parallax, realized that the unexplained motion of stars he had early observed with Samuel Molyneux was caused by the aberration of light.

The discovery was proof of a heliocentric model of the universe, since it is the revolution of the earth around the sun that causes an apparent motion in the observed position of a star.

[92] A new form of chemical nomenclature, developed by Louis Bernard Guyton de Morveau, with assistance from Lavoisier, classified elements binomially into a genus and a species.