Seagrass

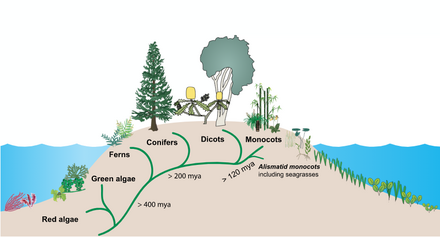

There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four families (Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and Cymodoceaceae), all in the order Alismatales (in the clade of monocotyledons).

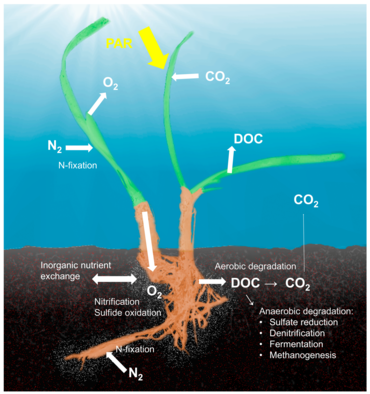

Like all autotrophic plants, seagrasses photosynthesize, in the submerged photic zone, and most occur in shallow and sheltered coastal waters anchored in sand or mud bottoms.

They function as important carbon sinks[3] and provide habitats and food for a diversity of marine life comparable to that of coral reefs.

[4] Though seagrasses provide invaluable ecosystem services by acting as breeding and nursery ground for a variety of organisms and promote commercial fisheries, many aspects of their physiology are not well investigated.

[10] The worldwide endangering of these sea meadows, which provide food and habitat for many marine species, prompts the need for protection and understanding of these valuable resources.

In addition to the ancestral traits of land plants one would expect habitat-driven adaptation process to the new environment characterized by multiple abiotic (high amounts of salt) and biotic (different seagrass grazers and bacterial colonization) stressors.

These seagrasses are generally short-lived and can recover quickly from disturbances by not germinating far away from parent meadows (e.g., Halophila sp., Halodule sp., Cymodocea sp., Zostera sp.

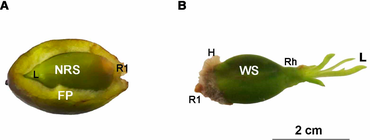

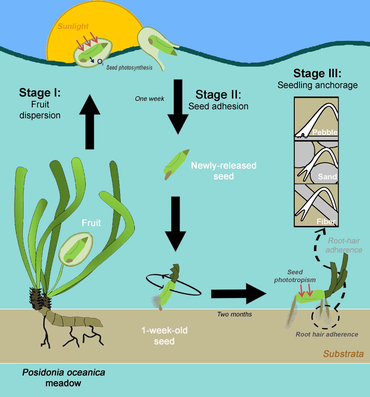

This strategy is typical of long-lived seagrasses that can form buoyant fruits with inner large non-dormant seeds, such as the genera Posidonia sp., Enhalus sp.

[39] P. oceanica meadows play important roles in the maintenance of the geomorphology of Mediterranean coasts, which, among others, makes this seagrass a priority habitat of conservation.

The large amounts of nutrient reserves contained in the seeds of this seagrass support shoot and root growth, even up to the first year of seedling development.

Subtidal light conditions can be estimated, with high accuracy, using artificial intelligence, enabling more rapid mitigation than was available using in situ techniques.

[58][59][60] Desiccation stress during low tide has been considered the primary factor limiting seagrass distribution at the upper intertidal zone.

[62][59] Intertidal seagrasses also show light-dependent responses, such as decreased photosynthetic efficiency and increased photoprotection during periods of high irradiance and air exposure.

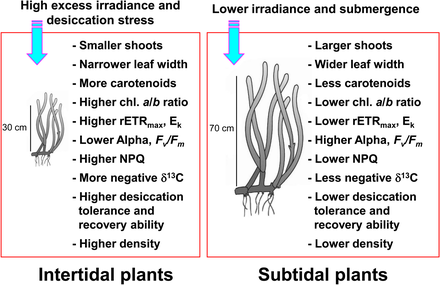

[68][69][70] As seagrasses in the intertidal and subtidal zones are under highly different light conditions, they exhibit distinctly different photoacclimatory responses to maximize photosynthetic activity and photoprotection from excess irradiance.

[citation needed] Seagrass beds are diverse and productive ecosystems, and can harbor hundreds of associated species from all phyla, for example juvenile and adult fish, epiphytic and free-living macroalgae and microalgae, mollusks, bristle worms, and nematodes.

Few species were originally considered to feed directly on seagrass leaves (partly because of their low nutritional content), but scientific reviews and improved working methods have shown that seagrass herbivory is an important link in the food chain, feeding hundreds of species, including green turtles, dugongs, manatees, fish, geese, swans, sea urchins and crabs.

[84][15][14] The long blades of seagrasses slow the movement of water which reduces wave energy and offers further protection against coastal erosion and storm surge.

It is estimated that 17 species of coral reef fish spend their entire juvenile life stage solely on seagrass flats.

[87] These habitats also act as a nursery grounds for commercially and recreationally valued fishery species, including the gag grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis), red drum, common snook, and many others.

In a recent publication, Dr. Ross Boucek and colleagues discovered that two highly sought after flats fish, the common snook and spotted sea trout provide essential foraging habitat during reproduction.

[90] Furthermore, many commercially important invertebrates also reside in seagrass habitats including bay scallops (Argopecten irradians), horseshoe crabs, and shrimp.

The high diversity of marine organisms that can be found on seagrass habitats promotes them as a tourist attraction and a significant source of income for many coastal economies along the Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean.

[98] Although most work on host-microbe interactions has been focused on animal systems such as corals, sponges, or humans, there is a substantial body of literature on plant holobionts.

[93] The microbial community in the P. oceanica rhizosphere shows similar complexity as terrestrial habitats that contain thousands of taxa per gram of soil.

[114][115][116][117][11] Thus, the cell walls of seagrasses seem to contain combinations of features known from both angiosperm land plants and marine macroalgae together with new structural elements.

Increased weather events, sea level rise, and higher temperatures as a result of global warming all have the potential to induce widespread seagrass loss.

In response to high nutrient levels, macroalgae form dense canopies on the surface of the water, limiting the light able to reach the benthic seagrasses.

Hypoxic conditions can eventually lead to seagrass die-off which creates a positive feedback cycle, where the decomposition of organic matter further decreases the amount of oxygen present in the water column.

These studies suggest that the presence of seagrass depends on physical factors such as temperature, salinity, depth and turbidity, along with natural phenomena like climate change and anthropogenic pressure.

Also, scientists, the public, and government officials should work in tandem to integrate traditional ecological knowledge and socio-cultural practices to evolve conservation policies.

dispersion, adhesion and settlement