Second Persian invasion of Greece

The Allied fleet had also withstood two days of Persian attacks at the Battle of Artemisium, but when news reached them of the disaster at Thermopylae, they withdrew to Salamis.

The Allied victory at Salamis prevented a quick conclusion to the invasion, and fearing becoming trapped in Europe, Xerxes retreated to Asia leaving his general Mardonius to finish the conquest with the elite of the army.

The Greeks would now move to the offensive, eventually expelling the Persians from Europe, the Aegean Islands and Ionia before the war finally came to an end in 449 BC with the Peace of Callias.

[5] As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally".

[12] The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus.

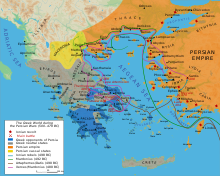

[17] A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the re-conquest of Thrace and forced Macedon to become a fully subordinate kingdom part of Persia.

)[21] Darius thus put together an ambitious task force under Datis and Artaphernes in 490 BC, which attacked Naxos, before receiving the submission of the other Cycladic Islands.

[23] Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.

[25] It was decided that Xerxes' Pontoon Bridges were to be set up to allow his army to cross the Hellespont to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos (rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC).

[35] The poet Simonides, who was a contemporary, talks of four million; Ctesias, based on Persian records, gave 800,000 as the total number of the army (without the support personnel) that was assembled by Xerxes.

[2] Modern scholars thus generally attribute the numbers given in the ancient sources to the result of miscalculations or exaggerations on the part of the victors, or disinformation by the Persians in the run up to the war.

[2][3] Nevertheless, whatever the real numbers were, it is clear that Xerxes was eager to ensure a successful expedition by mustering overwhelming numerical superiority by land and by sea,[2] and also that much of the army died of starvation and disease, never returning to Asia.

[36] An early and very influential modern historian, George Grote, set the tone by expressing incredulity at the numbers given by Herodotus: "To admit this overwhelming total, or anything near to it, is obviously impossible.

[69] A major limiting factor for the size of the Persian army, first suggested by Sir Frederick Maurice (a British transport officer) is the supply of water.

[102] This confederation had the power to send envoys asking for assistance and to dispatch troops from the member states to defensive points after joint consultation.

[116] When the Allies received the news that Xerxes was clearing paths around Mount Olympus, and thus intending to march towards Thermopylae, it was both the period of truce that accompanied the Olympic games, and the Spartan festival of Carneia, during both of which warfare was considered sacrilegious.

However, at the end of the second day, they were betrayed by a local resident named Ephialtes who revealed to Xerxes a mountain path that led behind the Allied lines.

When he was made aware of this maneuver (while the Immortals were still en route), Leonidas dismissed the bulk of the Allied army, remaining to guard the rear with 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebians and perhaps a few hundred others.

[130] The Peloponnesian Allies began to prepare a defensive line across the Isthmus of Corinth, building a wall, and demolishing the road from Megara, thereby abandoning Athens to the Persians.

[136][139] In summary, if Xerxes could destroy the Allied navy, he would be in a strong position to force a Greek surrender; this seemed the only hope of concluding the campaign in that season.

[142] Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet attacked, and scored a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships, and thus ensuring the Peloponnesus would not be outflanked.

[144] According to Herodotus, Mardonius volunteered to remain in Greece and complete the conquest with a hand-picked group of troops, while advising Xerxes to retreat to Asia with the bulk of the army.

[132] According to Herodotus a Persian general known as Artabazus escorted Xerxes to the Hellespont with 60,000 men; as he neared Pallene on the return journey to Thessaly: "he thought it right that he should enslave the people of Potidaea, whom he found in revolt".

[150] Mardonius moved to break the stalemate, by offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion to the Athenians (with the aim of thereby removing their fleet from the Allied forces), using Alexander I of Macedon as an intermediary.

[160][161] However, as at Thermopylae, the Persian infantry proved no match for the heavily armoured Greek hoplites,[162] and the Spartans broke through to Mardonius's bodyguard and killed him.

[166] Their morale boosted, the Allied marines fought and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Mycale that same day, destroying the remnants of the Persian fleet.

Moreover, the threat of future invasion was abated; although the Greeks remained worried that Xerxes would try again, over time it became apparent that the Persian desire to conquer Greece was much diminished.

[182] In the two major land battles of the invasion, the Allies clearly adjusted their tactics to nullify the Persian advantage in numbers and cavalry, by occupying the pass at Thermopylae and by staying on high ground at Plataea.

[185][192] At Plataea, the harassing of the Allied positions by cavalry was a successful tactic, forcing the precipitous (and nearly disastrous) retreat; however, Mardonius then brought about a general melee between the infantry, which resulted in the Persian defeat.

The major lesson of the invasion, reaffirming the events at the Battle of Marathon, was the superiority of the hoplite in close-quarters fighting over the more-lightly armed Persian infantry.