Sedition Act (Singapore)

According to one legal scholar, Koh Song Huat Benjamin and Ong Kian Cheong indicate that in Singapore freedom of speech is not a primary right, but is qualified by public order considerations couched in terms of racial and religious harmony.

[6] The Star Chamber, in the case of De Libellis Famosis (1572),[7] defined seditious libel (that is, sedition in a printed form) as the criticism of public persons or the government, and established it as a crime.

[8] Originally designed to protect the Crown and government from any potential uprising, sedition laws prohibited any acts, speech, or publications or writing that were made with seditious intent.

Seditious intent was broadly defined by the High Court of Justice in R. v. Chief Metropolitan Stipendiary, ex parte Choudhury (1990)[9] as "encouraging the violent overthrow of democratic institutions".

if such act, speech, words, publication or other thing has not otherwise in fact a seditious tendency.Although this statutory definition broadly corresponds to its common law counterpart,[24] there are two key differences.

A District Court held in Public Prosecutor v. Ong Kian Cheong (2009)[28] that on a plain and literal reading, there is no suggestion that Parliament intended to embody the common law of seditious libel into section 3(1)(e).

[30] In Public Prosecutor v. Koh Song Huat Benjamin (2005),[31] the accused persons pleaded guilty to doing seditious acts tending to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility.

Also, the seditious publications distributed by the accused persons which disparaged the Roman Catholic Church and other faiths were held to have affected followers comprising "different races and classes of the population in Singapore".

Hence, District Judge Neighbour's reliance in Ong Kian Cheong on the testimonies of a police officer and recipients of the tracts[33] has been criticized as "highly problematic", and it has been suggested that an objective test needs to be adopted to determine if an act will be offensive to other races or classes.

[56] In Koh Song Huat Benjamin, the District Court held that a conviction under section 4(1)(a) of the Sedition Act will be met with a sentence that promotes general deterrence.

[57] Similarly, in Ong Kian Cheong District Judge Neighbour relied on Justice V. K. Rajah's statement in Public Prosecutor v. Law Aik Meng (2007)[58] that there are many situations where general deterrence assumes significance and relevance, and one of them is offences involving community and/or race relations.

Even though the prosecution had only urged for the maximum fine permitted under the law to be imposed on one of the accused persons, his Honour felt that a nominal one-day imprisonment was also necessary to signify the seriousness of the offence.

[63] The significance of these mitigating factors was downplayed in Ong Kian Cheong, District Judge Neighbour observing that despite their presence the offences committed were serious in that they had the capacity to undermine and erode racial and religious harmony in Singapore.

He found that both the accused persons, by distributing the seditious and objectionable tracts to Muslims and the general public, clearly reflected their intolerance, insensitivity and ignorance of delicate issues concerning race and religion in Singapore's multiracial and multi-religious society.

Furthermore, in distributing the seditious and offensive tracts to spread their faith, the accused persons used the postal service to achieve their purpose and so were shielded by anonymity until the time they were apprehended.

[71] The High Court can issue a warrant authorizing a police officer not below the rank of sergeant to enter and search any specified premises, to seize any prohibited publications found, and to use necessary force in doing so.

[46] Without analysing Article 14(2) or factors such as the gravity of the threat to public order, the likelihood of disorder occurring, the speaker's intent, or the reasonableness of the audience, the District Court disagreed with this submission.

All that is needed to be proved is that the publication is question had a tendency to promote feelings of ill will and hostility between different races or classes of the population in Singapore.It has been argued that expediency may the correct standard for seditious speech that inflicts injury.

The Sedition Act, in prohibiting speech based upon mere proof of a "seditious tendency" regardless of the actual risks posed to public order, would not be in line with this proposed interpretation.

[84] It has been said it is a matter of speculation whether this reflects geopolitical realities or the Government's discharge of its duty under Article 152(2) of the Constitution to protect the interests of Malays and their religion as the indigenous people of Singapore.

[85] Professor Thio Li-ann has expressed the opinion that in Singapore free speech is not a primary right, but is qualified by public order considerations couched in terms of "racial and religious harmony".

[88] Furthermore, the judge did not deem the right of religious propagation guaranteed by Article 15(1) of the Constitution a mitigating factor because the accused persons, as Singaporeans, could not claim ignorance of the sensitive nature of race and religion in multiracial and multi-religious Singapore.

[92] There is an "intricate latticework of legislation" in Singapore to curb public disorder, which arguably gives effect to Parliament's intent to configure an overlapping array of arrangements,[93] and to leave the choice of a suitable response to prosecutorial discretion.

[96] In contrast with the punitive approach of the Sedition Act where a breach of the statute carries criminal liability, under the MRHA restraining orders may be imposed upon people causing feelings of enmity, hatred, ill-will or hostility between different religious groups, among other things.

[100] Another statutory counterpart to the Sedition Act is section 298A of the Penal Code,[101] which was introduced in 2007 to "criminalise the deliberate promotion by someone of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different racial and religious groups on grounds of race or religion".

Such a separate statutory provision could set out precise norms to regulate harmful non-political forms of speech with the goal of managing ethnic relations and promoting national identity.

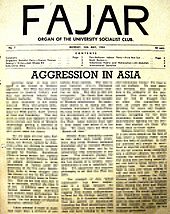

Eight students involved in the publication were charged under the Sedition Ordinance 1938 (S.S.) with possessing and distributing the newsletter, which was claimed to contain seditious articles that criticized the British colonial government.

[112] A third person, a 17-year-old youth named Gan Huai Shi, was also charged under the Sedition Act for posting a series of offensive comments about Malays on his blog entitled The Second Holocaust between April and July 2005.

Changes to the law included clarifying that calling for secession and promoting feelings of ill-will, hostility and hatred between people or groups of people on religious grounds amount to sedition; empowering the Public Prosecutor to call for bail to be denied to persons charged with sedition and for them to be prevented from leaving the country; introducing a minimum jail term of three years and extending the maximum term to 20 years; and enabling the courts to order that seditious material on the Internet be taken down or blocked.

[131] The case was brought by Dr. Azmi Sharom, a law professor from the University of Malaya who had been charged with sedition[132] for comments he made on the 2009 Perak constitutional crisis which were published on the website of The Malay Mail on 14 August 2014.