Self-reconfiguring modular robot

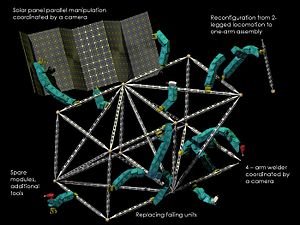

For example, a robot made of such components could assume a worm-like shape to move through a narrow pipe, reassemble into something with spider-like legs to cross uneven terrain, then form a third arbitrary object (like a ball or wheel that can spin itself) to move quickly over a fairly flat terrain; it can also be used for making "fixed" objects, such as walls, shelters, or buildings.

A feature found in some cases is the ability of the modules to automatically connect and disconnect themselves to and from each other, and to form into many objects or perform many tasks moving or manipulating the environment.

Some advantages of separating into multiple matrices include the ability to tackle multiple and simpler tasks at locations that are remote from each other simultaneously, transferring through barriers with openings that are too small for a single larger matrix to fit through but not too small for smaller matrix fragments or individual modules, and energy saving purposes by only utilizing enough modules to accomplish a given task.

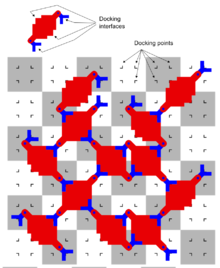

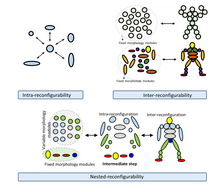

Modular self-reconfiguring robotic systems can be generally classified into several architectural groups by the geometric arrangement of their unit (lattice vs. chain).

Several systems exhibit hybrid properties, and modular robots have also been classified into the two categories of Mobile Configuration Change (MCC) and Whole Body Locomotion (WBL).

The added degrees of freedom make modular robots more versatile in their potential capabilities, but also incur a performance tradeoff and increased mechanical and computational complexities.

A second source of inspiration are biological systems that are self-constructed out of a relatively small repertoire of lower-level building blocks (cells or amino acids, depending on scale of interest).

What the researchers propose to make are moving, physical, three-dimensional replicas of people or objects, so lifelike that human senses would accept them as real.

One aspect of this application is that the main development thrust is geometric representation rather than applying forces to the environment as in a typical robotic manipulation task.

A third long-term vision for these systems has been called "bucket of stuff", which would be a container filled with modular robots that can accept user commands and adopt an appropriate form in order to complete household chores.

[6][7] The roots of the concept of modular self-reconfigurable robots can be traced back to the "quick change" end effector and automatic tool changers in computer numerical controlled machining centers in the 1970s.

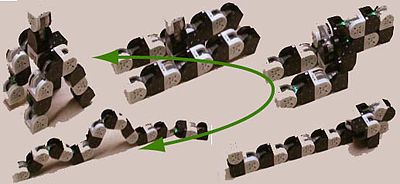

One of the more interesting hardware platforms recently has been the MTRAN II and III systems developed by Satoshi Murata et al.

A large effort at Carnegie Mellon University headed by Seth Goldstein and Todd Mowry has started looking at issues in developing millions of modules.

It is part of the PolyBot modular robot family that has demonstrated many modes of locomotion including walking: biped, 14 legged, slinky-like, snake-like: concertina in a gopher hole, inchworm gaits, rectilinear undulation and sidewinding gaits, rolling like a tread at up to 1.4 m/s, riding a tricycle, climbing: stairs, poles pipes, ramps etc.

As a chain type system, locomotion by CPG (Central Pattern Generator) controller in various shapes has been demonstrated by M-TRAN II.

Ref_1: see [3]; Ref_2: see [4] Stochastic-3D (2005) High spatial resolution for arbitrary three-dimensional shape formation with modular robots can be accomplished using lattice system with large quantities of very small, prospectively microscopic modules.

Three large scale prototypes were built in attempt to demonstrate dynamically programmable three-dimensional stochastic reconfiguration in a neutral-buoyancy environment.

[17] Molecubes (2005) This hybrid self-reconfiguring system was built by the Cornell Computational Synthesis Lab to physically demonstrate artificial kinematic self-reproduction.

Although each unit is capable of generating enough thrust to lift itself off the ground, on its own it is incapable of flight much like a helicopter cannot fly without its tail rotor.

This novel feature enables a single Roombots module to locomote on flat terrain, but also to climb a wall, or to cross a concave, perpendicular edge.

Roombots are designed for two tasks: to eventually shape objects of daily life, e.g. furniture, and to locomote, e.g. as a quadruped or a tripod robot made from multiple modules.

By the advantage of motion and connection, Sambot swarms can aggregate into a symbiotic or whole organism and generate locomotion as the bionic articular robots.

Inside the modular robot whose size is 80(W)X80(L)X102(H) mm, MCU (ARM and AVR), communication (Zigbee), sensors, power, IMU, positioning modules are embedded.

One of the key aspects of Symbrion is inspired by the biological world: an artificial genome that allows storing and evolution of suboptimal configurations in order to increase the speed of adaptation.

There are a number of fundamental limiting factors that govern this number: Though algorithms have been developed for handling thousands of units in ideal conditions, challenges to scalability remain both in low-level control and high-level planning to overcome realistic constraints: Though the advantages of Modular self-reconfiguring robotic systems is largely recognized, it has been difficult to identify specific application domains where benefits can be demonstrated in the short term.

Some suggested applications are Several robotic fields have identified Grand Challenges that act as a catalyst for development and serve as a short-term goal in absence of immediate killer apps.

The Grand Challenge is not in itself a research agenda or milestone, but a means to stimulate and evaluate coordinated progress across multiple technical frontiers.

Several Grand Challenges have been proposed for the modular self-reconfiguring robotics field: A unique potential solution that can be exploited is the use of inductors as transducers.

At the same time it could also be beneficial for its capabilities of docking detection (alignment and finding distance), power transmission, and (data signal) communication.

This medium is used to disseminate calls to workshops, special issues and other academic activities of interest to modular robotics researchers.