Selinunte

[7] On the other side Selinunte's territory certainly extended as far as the Halycus (modern Platani), at the mouth of which it founded the colony of Minoa, or Heracleia, as it was afterward called.

Like most of the Sicilian cities, it passed from an oligarchy to a tyranny, and about 510 BC was subject to a despot named Peithagoras, who was overthrown with the assistance of the Spartan Euryleon, one of the companions of Dorieus.

[11] Thucydides speaks of Selinunte just before the Athenian expedition in 416 BC as a powerful and wealthy city, possessing great resources for war both by land and sea, and having large stores of wealth accumulated in its temples.

They are, however, mentioned on several occasions providing troops to the Syracusans; and it was at Selinunte that the large Peloponnesian force sent to support Gylippus landed in the spring of 413 BC, having been driven over to the coast of Africa by a tempest.

[19] The Carthaginians in the following spring (409 BC) sent over a vast army containing 100,000 men, according to the lowest ancient estimate, led by Hannibal Mago (the grandson of Hamilcar that was killed at Himera).

The city fortifications were, in many places, in disrepair, and the armed forces promised by Syracuse, Acragas (modern Agrigento) and Gela, were not ready and did not arrive in time.

A considerable part of the citizens of Selinunte took up this offer, which was confirmed by the treaty subsequently concluded between Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse, and the Carthaginians, in 405 BC.

[28] But before the close of the war (about 250 BC), when the Carthaginians were beginning to pull back, and confine themselves to the defense of as few places as possible, they removed all the inhabitants of Selinunte to Lilybaeum and destroyed the city.

Pliny the Elder mentions its name (Selinus oppidum[30]), as if it still existed as a town in his time, but Strabo distinctly classes it with extinct cities.

[31] The Thermae Selinuntiae (at modern Sciacca), which derived their name from the ancient city, and seem to have been much frequented in the time of the Romans, were situated at a considerable distance, 30 km, from Selinunte: they are sulfurous springs, still much valued for their medical properties, and dedicated, like most thermal waters in Sicily, to San Calogero.

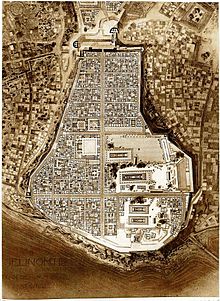

The part of the city on the Mannuzza Hill to the north, further inland, contained housing on the Hippodamian plan contemporary with the acropolis and two necropoleis (Galera-Bagliazzo and Manuzza).

The modern Archaeological park, which covers about 270 hectares can therefore be divided into the following areas:[33] The acropolis is on a limestone massif with a cliff face falling into the sea in the south, while the north end narrows to 140 m wide.

The pronaos of Temple A has a mosaic pavement showing symbolic figures of the Phoenician goddess Tanit, a caduceus, the Sun, a crown, and a bull's head, which testifies to the reuse of the space as a religious or domestic area in the Punic period.

Probably constructed around 250 BC, a short time before Selinus was abandoned for good, it represents the only religious building that attests to the modest revival of the city after its destruction in 409.

Its purpose remains obscure; in the past it was believed to be the Heroon of Empedocles, benefactor of the Selinuntine marshes,[36] but this theory is no longer sustainable, given the building's date.

They depict a crouching Sphinx in profile, the Delphic triad (Leto, Apollo, Artemis) in rigid frontal view, and the Rape of Europa.

They are paralleled by a long gallery (originally covered) with numerous vaulted passages, followed by a deep defensive ditch crossed by a bridge, with three semicircular towers at west, north, and east.

A Doric frieze at the top of the walls of the naos consisted of metopes depicting people, with the heads and naked parts of the women made of Parian marble and the rest from local stone.

Inside, there is a portico containing a second row of columns, a pronaos, a naos, and an adyton in single long, narrow structure (an archaic characteristic).

On the east side, two late archaic metopes (dated to 500 BC) were found in excavations in 1823, which depict Athena and Dionysus in the process of killing two giants.

At the foot of the hill by the mouth of the River Cottone was the East Port, which was more than 600 metres wide on the inside and was probably equipped with a mole or breakwater to protect the acropolis.

The extramural quarters, dedicated to trade, commerce and port activities was arranged on massive terraces on the hillslopes North of the modern village of Marinella, is the Buffa necropolis A path runs from the acropolis, over the river Modione to the west hill.

The complex, in varying states of preservation, was built in the sixth century BC on the slope of the hill and probably served as a station for funerary processions, before they proceeded to the Manicalunga necropolis.

Outside of the enclosure, the propylaea is flanked by the remains of a long portico (stoa) with seats for the pilgrims, who left evidence of themselves in the form of various altars and votives.

Just past the canal is the Temple of Demeter itself in the form of a megaron (20.4 x 9.52 metres), lacking a crepidoma or columns, but equipped with a pronaos, naos and adyton with a niche in the back.

Outside, to the west, the pious dedicated many small steles topped by images of the divine pair (two faces, one male and one female) made with shallow incisions.

A very large number of finds came from the Sanctuary of the Malophoros (all kept at the Museum in Palermo): carved reliefs of mythological scenes, around 12,000 votive figurines in terracotta from the seventh to fifth centuries BC; large bust-shaped censers depicting Demeter and perhaps Tanit, a great quantity of Corinthian pottery (late proto-Corinthian and early Corinthian), a bass-relief depicting the Rape of Persephone by Hades found at the entrance to the enclosure.

The sudden departure of the quarrymen, stonemasons and other workers means that today it is possible not just to reconstruct, but to see all the various stages of the quarrying process from the first deep circular cuts to the finished drums waiting to be transported.

The subject of this type evidently refers to a story related by Diogenes Laërtius[46] that the Selinuntines were afflicted with a pestilence from the marshy character of the lands adjoining the neighboring river, but that this was cured by works of drainage, suggested by Empedocles.

The Seal of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine is based on a coin of Selinus struck in 466 BC which was designed by the sculptor and medallist Allan Gairdner Wyon FRBS RMS (1882–1962).