Semiramis

Semiramis (/səˈmɪrəmɪs, sɪ-, sɛ-/;[1][page needed] Syriac: ܫܲܡܝܼܪܵܡ Šammīrām, Armenian: Շամիրամ Šamiram, Greek: Σεμίραμις, Arabic: سميراميس Samīrāmīs) was the legendary[2][3] Lydian-Babylonian[4][5] wife of Onnes and of Ninus, who succeeded the latter on the throne of Assyria,[6] according to Movses Khorenatsi.

[7] Legends narrated by Diodorus Siculus, who drew primarily from the works of Ctesias of Cnidus,[8][9] describe her and her relationships to Onnes and King Ninus.

Armenians and the Assyrians of Iraq, northeast Syria, southeast Turkey, and northwest Iran still use Shamiram and its derivative Samira as a given name for girls.

It has been speculated that being a woman who ruled successfully may have made the Assyrians regard her with particular reverence and that her achievements may have been retold over the generations until she was gradually turned into a legendary figure.

[12] The name of Semiramis came to be applied to various monuments in Western Asia and Anatolia whose origins had been forgotten or unknown,[13] even the Behistun Inscription of Darius.

[17] Various places in Mesopotamia, Media, Persia, the Levant, Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Caucasus received names recalling Semiramis.

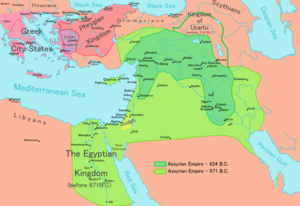

[11] Thus, during that time Shammuramat could have been in control of the vast Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), which stretched from the Caucasus Mountains in the north to the Arabian Peninsula in the south, and from western Iran in the east to Cyprus in the west.

"[12] According to Diodorus, a first century BC Greek historian, Semiramis was of noble parents, the daughter of the fish-goddess Derketo of Ascalon and of a mortal.

He tried to compel Onnes to give her to him as a wife, first offering his own daughter Sonanê in return and eventually threatening to put out his eyes as punishment.

This ploy succeeded initially, but she was wounded in the counterattack and her army mainly annihilated, forcing the surviving remnants to re-ford the Indus and retreat to the west.

[28] The name of Semiramis came to be applied to various monuments in Western Asia and Anatolia, the origins of which ancient writers sometimes asserted had been forgotten or unknown.

[29] Herodotus, an ancient Greek writer, geographer, and historian living from c. 484 to 425 BC, ascribes to Semiramis the artificial banks that confined the Euphrates[16] and knows her name as borne by a gate of Babylon.

[17] Strabo, a Greek geographer, philosopher, and historian who lived in Asia Minor during 64 or 63 BC to 24 AD, credits her with building earthworks and other structures "throughout almost the whole continent".

One story claimed that she had an incestuous relationship with her son, justified it by passing a law to legitimize parent-child marriages, and invented the chastity belt to deter any romantic rivals before he eventually killed her.

She is included in De Mulieribus Claris, a collection of biographies of historical and mythological women by the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio that was composed in 1361–1362.

She was included in Christine de Pizan's The Book of the City of Ladies, finished by 1405, and, starting in the fourteenth century, she was commonly found on the Nine Worthies list for women.

[35][36] Semiramis appears in many plays, such as Voltaire's tragedy Sémiramis and Pedro Calderón de la Barca's drama La hija del aire, and in operas by dozens of composers[39] including Antonio Vivaldi, Christoph Willibald Gluck, Domenico Cimarosa, Josef Mysliveček, Giacomo Meyerbeer, and Gioachino Rossini.

He said that Semiramis and Nimrod's incestuous male offspring was the Akkadian deity Tammuz, and that all divine pairings in religions were retellings of this story.