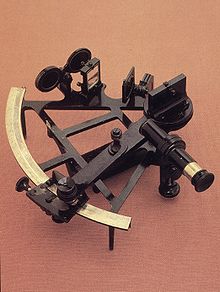

Sextant

A sextant is a doubly reflecting navigation instrument that measures the angular distance between two visible objects.

The primary use of a sextant is to measure the angle between an astronomical object and the horizon for the purposes of celestial navigation.

[1] A sextant can also be used to measure the lunar distance between the moon and another celestial object (such as a star or planet) in order to determine Greenwich Mean Time and hence longitude.

The principle of the instrument was first implemented around 1731 by John Hadley (1682–1744) and Thomas Godfrey (1704–1749), but it was also found later in the unpublished writings of Isaac Newton (1643–1727).

The sextant is not dependent upon electricity (unlike many forms of modern navigation) or any human-controlled signals (such as GPS).

The frame of a sextant is in the shape of a sector which is approximately 1⁄6 of a circle (60°),[2] hence its name (sextāns, sextantis is the Latin word for "one sixth").

The scale must be graduated so that the marked degree divisions register twice the angle through which the index arm turns.

For example, the sextant illustrated has a scale graduated from −10° to 142°, which is basically a quintant: the frame is a sector of a circle subtending an angle of 76° at the pivot of the index arm.

An artificial horizon can consist simply of a pool of water shielded from the wind, allowing the user to measure the distance between the body and its reflection, and divide by two.

The filters usually consist of a series of progressively darker glasses that can be used singly or in combination to reduce haze and the Sun's brightness.

Many users prefer a simple sighting tube, which has a wider, brighter field of view and is easier to use at night.

The standard frame designs (see illustration) are supposed to equalise differential angular error from temperature changes.

Solid brass frame sextants are less susceptible to wobbling in high winds or when the vessel is working in heavy seas, but as noted are substantially heavier.

Essentially, a sextant is intensely personal to each navigator, and they will choose whichever model has the features which suit them best.

Some also had mechanical averagers to make hundreds of measurements per sight for compensation of random accelerations in the artificial horizon's fluid.

With these, the navigator pre-computed their sight and then noted the difference in observed versus predicted height of the body to determine their position.

On a vessel at sea even on misty days a sight may be done from a low height above the water to give a more definite, better horizon.

Releasing the index bar (either by releasing a clamping screw, or on modern instruments, using the quick-release button), and moving it towards higher values of the scale, eventually the image of the Sun will reappear on the index mirror and can be aligned to about the level of the horizon on the horizon mirror.

Then the fine adjustment screw on the end of the index bar is turned until the bottom curve (the lower limb) of the Sun just touches the horizon.

[5] An alternative method is to estimate the current altitude (angle) of the Sun from navigation tables, then set the index bar to that angle on the arc, apply suitable shades only to the index mirror, and point the instrument directly at the horizon, sweeping it from side to side until a flash of the Sun's rays are seen in the telescope.

[5] Star and planet sights are normally taken during nautical twilight at dawn or dusk, while both the heavenly bodies and the sea horizon are visible.