Ships of ancient Rome

The galley was a long, narrow, highly maneuverable ship powered by oarsmen, sometimes stacked in multiple levels such as biremes or triremes, and many of which also had sails.

[5] By 260 BC the war had reached a stalemate, as the Carthaginians focused on defending their well-fortified Sicilian towns and cities; these were mostly on the coast and so could be supplied and reinforced without the Romans being able to use their superior army to interdict.

[6][7] The focus of the war shifted to the sea, where the Romans had little experience; on the few occasions they had previously felt the need for a naval presence they had usually relied on small squadrons provided by their Latin or Greek allies.

During this time, most of the galley crews were disbanded or employed for entertainment purposes in mock battles or in handling the sail-like sun-screens in the larger Roman arenas.

What fleets remained were treated as auxiliaries of the land forces, and galley crewmen themselves called themselves milites, "soldiers", rather than nautae, "sailors".

[22] The Roman galley fleets were turned into provincial patrol forces that were smaller and relied largely on liburnians, compact biremes with 25 pairs of oars.

These were named after an Illyrian tribe known by Romans for their sea roving practices, and these smaller craft were based on, or inspired by, their vessels of choice.

The liburnians and other small galleys patrolled the rivers of continental Europe and reached as far as the Baltic, where they were used to fight local uprisings and assist in checking foreign invasions.

The Romans maintained numerous bases around the empire: along the rivers of Central Europe, chains of forts along the northern European coasts and the British Isles, Mesopotamia, and North Africa, including Trabzon, Vienna, Belgrade, Dover, Seleucia, and Alexandria.

It has been estimated that it cost less for a sailing ship of the Roman Empire to carry grain the length of the Mediterranean than to move the same amount 15 miles (24 km) by road.

[25][a] Merchant ships, such as naves onerariae, had always been pressed into service for military purposes such as for transporting troops to North Africa in the Second Punic war.

In 47 BCE, Publius Vatinius equipped actuariae at Brindisi with temporary rams to support Julius Caesar's forces in Illyricum, on the other side of the Adriatic, though these were only suitable to combat smaller enemy vessels.

The bireme was also recorded in ancient history on the 8th and early 7th-century BC Assyrian reliefs, where they were used to carry out an amphibious attack on the coast of Elam and the lagoons of the Persian Gulf during the reign of Sennacherib.

Liburnae played a key role in the Battle of Actium in Greece (31 BCE), which saw the establishment of Augustus as the undisputed ruler of the Roman world.

[citation needed] Gradually, liburna became a generic term for various types of Roman ships, including cargo vessels in late antiquity.

Nimble, graceful, and of shallow draft, such a vessel was used on northern rivers close to the Limes Germanicus, the Germanic borderlands, and thus saw service on the Rhine and the Danube.

Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus mentioned the navis lusoria in his writings,[47][48] but not much was learned about them until the discovery of such boats at Mainz, Germany in 1981–82.

[56] This allowed Roman legionaries acting as marines to board enemy ships and capture them, rather than employing the previously traditional tactic of ramming.

Despite the attempts to counter increasingly heavy ships, ramming tactics were superseded in the last centuries BC by the Macedonians and Romans who were primarily land-based powers.

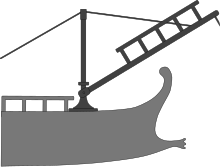

[68] The Romans baffled the ramming tactics of the Carthaginians by the invention of the corvus, or crow, a plank with a spike for hooking onto enemy ships which grappled the prow of the rammer, and provided a gangway for boarders.

[69] The Romans did continue their boarding tactics in the naval battles of the Punic Wars, but are also reported as ramming the Carthaginian vessels after the abandonment of the corvus.

[70] All warships were equipped with rams, a triple set of 60-centimetre-wide (2 ft) bronze blades weighing up to 270 kilograms (600 lb) positioned at the waterline.

[79] Success in ramming depended so much on a combination of skill and good fortune that it played a somewhat subordinate part in most ancient sea fights.

The ram was replaced by a long spur in the bow that was designed to break oars and to act as a boarding platform for storming enemy ships.

[82] During the First Punic War, the admiralty of the Roman Republic conceived new and progressive ways of fleet construction, development and composition in order to successfully engage the Carthaginian navy.

In 1976, Willard Bascom suggested that the deep, anoxic waters of the Black Sea might have preserved ships from antiquity since typical wood-devouring organisms could not survive there.

[115] Based on the dimensions of the recovered rams, the archaeologists who have studied them believe that they all came from triremes, contrary to Polybius's account of all of the warships involved being quinqueremes.

She was built to drawings by the naval architect John F. Coates which he developed through long discussions with the historian J. S. Morrison following the longest correspondence on any subject in The Times in the early 1980s.

The work was also advised by the classics teacher Charles Willink and drew on evidence gained from Greek literature, history of art and archaeology above and below water.

In 2006, the Regina travelled from Regensburg to Budapest covering distances of up to 100 km (54 nmi) per day confirming that the vessel was speedy and demonstrating the great mobility the military could achieve by its use.