Samaria

The Palestinian Authority and the international community do not recognize the term "Samaria"; in modern times, the territory is generally known as part of the West Bank.

[6] In Nelson's Encyclopaedia (1906–1934), the Samaria region in the three centuries following the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel, i.e. during the Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian periods, is described as a "province" that "reached from the [Mediterranean] sea to the Jordan Valley".

[3]During the first century, the boundary between Samaria and Judea passed eastward of Antipatris, along the deep valley which had Beth Rima (now Bani Zeid al-Gharbia) and Beth Laban (today's al-Lubban al-Gharbi) on its southern, Judean bank; then it passed Anuath and Borceos, identified by Charles William Wilson (1836–1905) as the ruins of 'Aina and Khirbet Berkit; and reached the Jordan Valley north of Acrabbim and Sartaba.

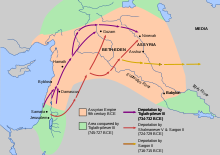

[2] Over time, the region has been controlled by numerous different civilizations, including Canaanites, Israelites, Neo-Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Seleucids, Hasmoneans, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Crusaders, and Ottoman Turks.

[18] The archaeological record suggests that Samaria experienced significant settlement growth in Iron Age II (from c. 950 BC).

According to botanists, the majority of Samaria's forests were torn down during the Iron Age II, and were replaced by plantations and agricultural fields.

[24] According to many scholars, archaeological excavations at Mount Gerizim indicate that a Samaritan temple was built there in the first half of the 5th century BCE.

[29] The date of the schism between Samaritans and Jews is unknown, but by the early 4th century BCE the communities seem to have had distinctive practices and communal separation.

[31] The transfer of three districts of Samaria— Ephraim, Lod and Ramathaim—under the control of Judea in 145 BCE as part of an agreement between Jonathan Apphus and Demetrius II is one indication of this decline.

The impact of the Jewish–Roman wars is archaeologically evident in Jewish-inhabited areas of southern Samaria, as many sites were destroyed and left abandoned for extended periods of time.

[34][35] An apparent new wave of settlement growth in southern Samaria, most likely by non-Jews, can be traced back to the late Roman and Byzantine eras.

[43] Based on historical sources and archeological data, the Manasseh Hill surveyors concluded that Samaria's population during the Byzantine period was composed of Samaritans, Christians, and a minority of Jews.

[44] The Samaritan population was mainly concentrated in the valleys of Nablus and to the north as far as Jenin and Kfar Othenai; they did not settle south of the Nablus-Qalqiliya line.

With the exception of Neapolis, Sebastia, and a small cluster of monasteries in central and northern Samaria, most of the population of the rural areas remained non-Christian.

[45] In southwestern Samaria, a significant concentration of churches and monasteries was discovered, with some of them built on top of citadels from the late Roman period.

Magen raised the hypothesis that many of these were used by Christian pilgrims, and filled an empty space in the region whose Jewish population was wiped out in the Jewish–Roman wars.

[47][48][49] Evidence implies that a large number of Samaritans converted under Abbasid and Tulunid rule, as a result of droughts, earthquakes, religious persecution, high taxes, and anarchy.

[51] As a result, today much of the local population resides in towns and villages, and the Bedouin settlement may explain the tribal organization found in parts of the rural society, known as the 'ushrān.

The 1947 UN partition plan called for the Arab state to consist of several parts, the largest of which was described as "the hill country of Samaria and Judea.

Jordan ceded its claims in the West Bank (except for certain prerogatives in Jerusalem) to the PLO in November 1988, later confirmed by the Israel–Jordan Treaty of Peace of 1994.

It has produced various basic statistical series on the territories, dealing with population, employment, wages, external trade, national accounts, and various other topics.

"[59] The Palestinian Authority however use Nablus, Jenin, Tulkarm, Qalqilya, Salfit, Ramallah and Tubas governorates as administrative centers for the same region.

[63] The ancient site of Samaria-Sebaste covers the hillside overlooking the West Bank village of Sebastia on the eastern slope of the hill.

[65] Archaeological finds from Roman-era Sebaste, a site that was rebuilt and renamed by Herod the Great in 30 BC, include a colonnaded street, a temple-lined acropolis, and a lower city, where John the Baptist is believed to have been buried.

[67] The findings included Hebrew, Aramaic, cuneiform and Greek inscriptions, as well as pottery remains, coins, sculpture, figurines, scarabs and seals, faience, amulets, beads and glass.

The reverse side depicts the Persian King in his kandys robe facing down a lion that is standing on its hind legs.

[70] The Samaritans (Hebrew: Shomronim) are an ethnoreligious group named after and descended from ancient Semitic inhabitants of Samaria, since the Assyrian exile of the Israelites, according to 2 Kings 17 and first-century historian Josephus.

[75] The animals that dominate the general area have their origins in the Mediterranean basin and in Europe, such as the badger, the wild boar, the red fox, the hedgehog, the field mouse, and the mole (among mammals).