Aramaic

Aramaic (Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: ארמית, romanized: ˀərāmiṯ; Classical Syriac: ܐܪܡܐܝܬ, romanized: arāmāˀiṯ[a]) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, southeastern Anatolia, Eastern Arabia[3][4] and the Sinai Peninsula, where it has been continually written and spoken in different varieties[5] for over three thousand years.

[22][23] Aramaic dialects today form the mother tongues of the Arameans (Syriacs) in the Qalamoun mountains, Assyrians of Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran and Mandaeans, as well as some Mizrahi Jews.

[5] Aramaicist Holger Gzella [de] notes, "The linguistic history of Aramaic prior to the appearance of the first textual sources in the ninth century BC remains unknown.

[52][53] In 1819–21 Ulrich Friedrich Kopp published his Bilder und Schriften der Vorzeit ("Images and Inscriptions of the Past"), in which he established the basis of the paleographical development of the Northwest Semitic scripts.

[69][70] Ancient Aram, bordering northern Israel and what is now called Syria, is considered the linguistic center of Aramaic, the language of the Arameans who settled the area during the Bronze Age c. 3500 BC.

In fact, Arameans carried their language and writing into Mesopotamia by voluntary migration, by forced exile of conquering armies, and by nomadic Chaldean invasions of Babylonia during the period from 1200 to 1000 BC.

Since the name of Syria itself emerged as a variant of Assyria,[72][73] the biblical Ashur,[74] and Akkadian Ashuru,[75] a complex set of semantic phenomena was created, becoming a subject of interest both among ancient writers and modern scholars.

[27][29] Beginning with the rise of the Rashidun Caliphate and the early Muslim conquests in the late seventh century, Arabic gradually replaced Aramaic as the lingua franca of the Near East.

Aramaic also continues to be spoken by the Assyrians of northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey, and northwest Iran, with diaspora communities in Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and southern Russia.

However, there are several sizable Assyrian towns in northern Iraq, such as Alqosh, Bakhdida, Bartella, Tesqopa, and Tel Keppe, and numerous small villages, where Aramaic is still the main spoken language, and many large cities in this region also have Suret-speaking communities, particularly Mosul, Erbil, Kirkuk, Dohuk, and al-Hasakah.

Although there are some exceptions to this rule, this classification gives "Old", "Middle", and "Modern" periods alongside "Eastern" and "Western" areas to distinguish between the various languages and dialects that are Aramaic.

The more widely spoken Eastern Aramaic languages are largely restricted to Assyrian, Mandean and Mizrahi Jewish communities in Iraq, northeastern Syria, northwestern Iran, and southeastern Turkey, whilst the severely endangered Western Neo-Aramaic language is spoken by small Christian and Muslim communities in the Anti-Lebanon mountains, and closely related western varieties of Aramaic[95] persisted in Mount Lebanon until as late as the 17th century.

[96] The term "Old Aramaic" is used to describe the varieties of the language from its first known use, until the point roughly marked by the rise of the Sasanian Empire (224 AD), dominating the influential, eastern dialect region.

The period before this, dubbed "Ancient Aramaic", saw the development of the language from being spoken in Aramaean city-states to become a major means of communication in diplomacy and trade throughout Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Egypt.

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, local vernaculars became increasingly prominent, fanning the divergence of an Aramaic dialect continuum and the development of differing written standards.

Imperial Aramaic was highly standardised; its orthography was based more on historical roots than any spoken dialect, and the inevitable influence of Persian gave the language a new clarity and robust flexibility.

For centuries after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire (in 330 BC), Imperial Aramaic – or a version thereof near enough for it to be recognisable – would remain an influence on the various native Iranian languages.

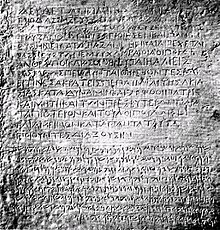

However, Aramaic continued to be used, in its post-Achaemenid form, among upper and literate classes of native Aramaic-speaking communities, and also by local authorities (along with the newly introduced Greek).

The Persian Sassanids, who succeeded the Parthian Arsacids in the mid-3rd century AD, subsequently inherited/adopted the Parthian-mediated Aramaic-derived writing system for their own Middle Iranian ethnolect as well.

The kingdom (c. 200 BC – 106 AD) controlled the region to the east of the Jordan River, the Negev, the Sinai Peninsula, and the northern Hijaz, and supported a wide-ranging trade network.

After annexation by the Romans in 106 AD, most of Nabataea was subsumed into the province of Arabia Petraea, the Nabataeans turned to Greek for written communications, and the use of Aramaic declined.

In the Kingdom of Osroene, founded in 132 BCE and centred in Edessa (Urhay), the regional dialect became the official language: Edessan Aramaic (Urhaya), that later came to be known as Classical Syriac.

[135] Classical Mandaic, used as a liturgical language by the Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, is a sister dialect to Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, though it is both linguistically and culturally distinct.

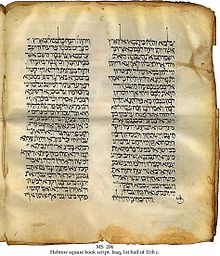

It is the linguistic setting for the Jerusalem Talmud (completed in the 5th century), Palestinian targumim (Jewish Aramaic versions of scripture), and midrashim (biblical commentaries and teaching).

The standard vowel pointing for the Hebrew Bible, the Tiberian system (7th century), was developed by speakers of the Galilean dialect of Jewish Middle Palestinian.

Having largely lived in remote areas as insulated communities for over a millennium, the remaining speakers of modern Aramaic dialects, such as the Arameans of the Qalamoun Mountains, Assyrians, Mandaeans and Mizrahi Jews, escaped the linguistic pressures experienced by others during the large-scale language shifts that saw the proliferation of other tongues among those who previously did not speak them, most recently the Arabization of the Middle East and North Africa by Arabs beginning with the early Muslim conquests of the seventh century.

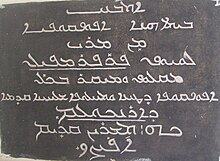

Matthew 28, verse 16, in Classical Syriac (Eastern accent), Western Neo-Aramaic, Turoyo and Suret (Swadaya): Each dialect of Aramaic has its own distinctive pronunciation, and it would not be feasible here to go into all these properties.

Some modern Aramaic pronunciations lack the series of "emphatic" consonants, and some have borrowed from the inventories of surrounding languages, particularly Arabic, Azerbaijani, Kurdish, Persian, and Turkish.

This is then modified by the addition of vowels and other consonants to create different nuances of the basic meaning: Aramaic nouns and adjectives are inflected to show gender, number and state.

Verb forms are marked for person (first, second or third), number (singular or plural), gender (masculine or feminine), tense (perfect or imperfect), mood (indicative, imperative, jussive, or infinitive), and voice (active, reflexive, or passive).