Shunga

Shunga (春画) is a type of Japanese erotic art typically executed as a kind of ukiyo-e, often in woodblock print format.

He, like many artists of his time, tended to draw genital organs in an oversized manner, similar to a common shunga topos.

Through the medium of narrative handscrolls, sexual scandals from the imperial court or the monasteries were depicted, and the characters tended to be limited to courtiers and monks.

However, since for several decades following this edict, publishing guilds saw fit to send their members repeated reminders not to sell erotica, it seems probable that production and sales continued to flourish.

[4][failed verification] According to Monta Hayakawa and C. Andrew Gerstle, westerners during the nineteenth century were less appreciative of shunga because of its erotic nature.

[5] In the journal of Francis Hall, an American businessperson who arrived in Yokohama in 1859, he described shunga as "vile pictures executed in the best style Japanese art.

"[5] Hayakawa stated that Hall was shocked and disgusted when on two occasions his Japanese acquaintances and their wives showed him shunga at their homes.

[5] Shunga also faced problems in Western museums in the twentieth century; Peter Webb reported that while engaged in research for a 1975 publication, he was initially informed that no relevant material existed in the British Museum, and when finally allowed access to it, he was told that it "could not possibly be exhibited to the public" and had not been catalogued.

[6] The introduction of Western culture and technologies at the beginning of the Meiji era (1868–1912), particularly the importation of photo-reproduction techniques, had serious consequences for shunga.

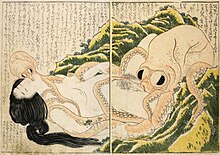

This led to the appearance of shunga by renowned artists, such as the ukiyo-e painter perhaps best known in the Western world, Hokusai (see The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife from the series Kinoe no Komatsu).

Ukiyo-e artists owed a stable livelihood to such customs, and producing a piece of shunga for a high-ranking client could bring them sufficient funds to live on for about six months.

However, between 1761 and 1786 the implementation of printing regulations became more relaxed, and many artists took to concealing their name as a feature of the picture (such as calligraphy on a fan held by a courtesan) or allusions in the work itself (such as Utamaro's empon entitled Utamakura).

Some writers on the subject refer to this as the creation of a world parallel to contemporary urban life, but idealised, eroticised and fantastical.

[1][4] By far the majority of shunga depict the sexual relations of the ordinary people, the chōnin, the townsmen, women, merchant class, artisans and farmers.

[8] Similarly, boys of the Wakashū age range were considered erotically attractive and often performed the female parts in kabuki productions.

Both painted handscrolls and illustrated erotic books (empon) often presented an unrelated sequence of sexual tableaux, rather than a structured narrative.

This is primarily because nudity was not inherently erotic in Tokugawa Japan – people were used to seeing the opposite sex naked in communal baths.

It also served an artistic purpose; it helped the reader identify courtesans and foreigners, the prints often contained symbolic meaning, and it drew attention to the parts of the body that were revealed, i.e., the genitalia.

From The Adonis Plant (Fukujusō) Woodblock print, from a set of 12, ōban c. 1815

A tryst between a young man and a boy. See Nanshoku .

Miyagawa Isshō , c. 1750 ; Shunga hand scroll (kakemono-e); sumi, color and gofun on silk. Private collection.