Siege of Pamplona (1813)

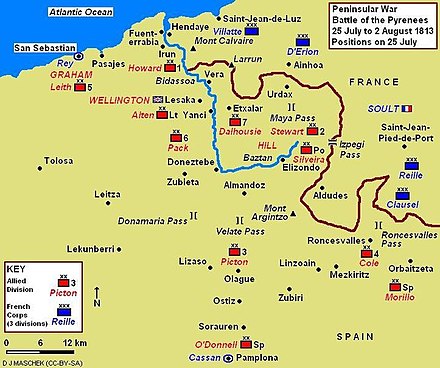

In late July 1813, Marshal Nicolas Soult attempted to relieve the city but his operation failed in the Battle of the Pyrenees.

The surrender negotiations were marred by French bluffs to blow up the fortifications and Spanish threats to massacre the garrison, neither of which occurred.

Other reasons were that the British and Portuguese had not fully established their new supply line via the port of Santander, the army was experiencing serious straggling and there was political trouble with the Cortes of Cádiz.

[7] While his army was preparing to lunge forward, four French divisions under Clausel were far away in the Pyrenees trying to hunt down Francisco Espoz y Mina and his Spanish guerillas.

On 12–13 May, Clausel attacked Mina's base at Roncal but the guerilla leader escaped its destruction and the subsequent French pursuit.

[10] After a few days of hard marching, Wellington gave up the futile chase of Clausel's column on 29 June and turned his four divisions back toward Pamplona.

[12] Since O'Donnell's 11,000 men of the Army of Reserve of Andalusia had recently forced the surrender of the Pancorbo forts, on 2 July Wellington ordered the Spaniard to bring his troops to blockade Pamplona.

When his beaten army passed Pamplona, Joseph and Jourdan sent their unfit and sick soldiers into the fortress, as well as 40 men captured from the 71st Foot at Vitoria.

[19] On 27 June Cassan mounted a sortie toward Villava on the north side of the fortress, but it failed to press back the Allied defenders.

That day, Carlos de España's Spanish division arrived to plug the gap on the south side of Pamplona.

[20] Despite the great disappointment of witnessing the failed relief of the city, Cassan managed to hold his soldiers to their duty for three more months.

Cassan tried to send the civilian population out of Pamplona, but de España ordered them to be fired upon and they fled back into the city.

In desperation, the starving soldiers killed dogs, cats and rats and then dug up roots, some of which turned out to be poison hemlock.

At this time, a stream of deserters began tricking out of the city; these were mostly Germans, Italians, Belgians and Spaniards who had joined the pro-French forces.

The Spanish general promised that if the French blew up the fortress, he would order his men to take no prisoners and that the peasants would probably kill anyone who escaped.

[22] Wellington wrote a letter to de España that the French officers should be shot and the common soldiers decimated if they damaged the city.

[22] Finally, Cassan had to accept terms which allowed his soldiers to march out with the honors of war, but lay down their arms 300 yards (274 m) from the gates and be sent to prison camps in England.

[23] Historian Digby Smith gave French losses as 500 killed, 800 wounded, and 2,150 captured while estimating that the 10,000-strong Spanish besiegers sustained 2,000 casualties during the siege.

[19] Oman noted that it was fortunate that the negotiations ended in a peaceful surrender, because de España's behavior during the First Carlist War showed that he was cruel enough to resort to massacre.

The British commander thought that if the wheat fields had been burned and the gardens ruined that Pamplona would have fallen three weeks earlier.

[16] In fact, Cassan's ability to hold out into the autumn forced Wellington to keep Hill's corps at the Roncevaux Pass where it endured constant rain and snow that put many soldiers in the hospital.