Slide rule

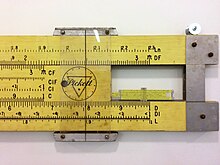

A slide rule is a hand-operated mechanical calculator consisting of slidable rulers for evaluating mathematical operations such as multiplication, division, exponents, roots, logarithms, and trigonometry.

Though similar in name and appearance to a standard ruler, the slide rule is not meant to be used for measuring length or drawing straight lines.

Maximum accuracy for standard linear slide rules is about three decimal significant digits, while scientific notation is used to keep track of the order of magnitude of results.

English mathematician and clergyman Reverend William Oughtred and others developed the slide rule in the 17th century based on the emerging work on logarithms by John Napier.

[3] The slide rule's ease of use, ready availability, and low cost caused its use to continue to grow through the 1950s and 1960s, even as desktop electronic computers were gradually introduced.

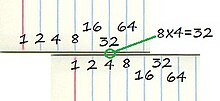

Calculations that can be reduced to simple addition or subtraction using those precomputed functions can be solved by aligning the two rulers and reading the approximate result.

A sliding cursor with a vertical alignment line is used to find corresponding points on scales that are not adjacent to each other or, in duplex models, are on the other side of the rule.

Addition and subtraction aren't typically performed on slide rules, but is possible using either of the following two techniques:[8] Using (almost) any strictly monotonic scales, other calculations can also be made with one movement.

With the aid of scales printed on the frame it also helps with such miscellaneous tasks as converting time, distance, speed, and temperature values, compass errors, and calculating fuel use.

While GPS has reduced the use of dead reckoning for aerial navigation, and handheld calculators have taken over many of its functions, the E6-B remains widely used as a primary or backup device and the majority of flight schools demand that their students have some degree of proficiency in its use.

In 1895, a Japanese firm, Hemmi, started to make slide rules from celluloid-clad bamboo, which had the advantages of being dimensionally stable, strong, and naturally self-lubricating.

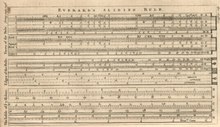

In 1620 Edmund Gunter of Oxford developed a calculating device with a single logarithmic scale; with additional measuring tools it could be used to multiply and divide.

In 1845, Paul Cameron of Glasgow introduced a nautical slide rule capable of answering navigation questions, including right ascension and declination of the sun and principal stars.

The growth of the engineering profession during the later 19th century drove widespread slide-rule use, beginning in Europe and eventually taking hold in the United States as well.

[citation needed] In the 1920s, the novelist and engineer Nevil Shute Norway (he called his autobiography Slide Rule) was Chief Calculator on the design of the British R100 airship for Vickers Ltd. from 1924.

After months of labour filling perhaps fifty foolscap sheets with calculations "the truth stood revealed (and) produced a satisfaction almost amounting to a religious experience".

In 2004, education researchers David B. Sher and Dean C. Nataro conceived a new type of slide rule based on prosthaphaeresis, an algorithm for rapidly computing products that predates logarithms.

[28] A Department of Defense publication from 1962[29] infamously included a special-purpose circular slide rule for calculating blast effects, overpressure, and radiation exposure from a given yield of an atomic bomb.

[30] The importance of the slide rule began to diminish as electronic computers, a new but rare resource in the 1950s, became more widely available to technical workers during the 1960s.

The HP used the CORDIC (coordinate rotation digital computer) algorithm,[34] which allows for calculation of trigonometric functions using only shift and add operations.

[40] This led engineers to use mathematical equations that favored operations that were easy on a slide rule over more accurate but complex functions; these approximations could lead to inaccuracies and mistakes.

[41] On the other hand, the spatial, manual operation of slide rules cultivates in the user an intuition for numerical relationships and scale that people who have used only digital calculators often lack.

[43] A slide rule requires the user to separately compute the order of magnitude of the answer to position the decimal point in the results.

Many sailors keep slide rules as backups for navigation in case of electric failure or battery depletion on long route segments.

Many rules found for sale on online auction sites are damaged or have missing parts, and the seller may not know enough to supply the relevant information.

The Keuffel and Esser rules from the period up to about 1950 are particularly problematic, because the end-pieces on the cursors, made of celluloid, tend to chemically break down over time.

Methods of preserving plastic may be used to slow the deterioration of some older slide rules, and 3D printing may be used to recreate missing or irretrievably broken cursor parts.

The Concise Company of Tokyo, which began as a manufacturer of circular slide rules in July 1954,[47] continues to make and sell them today.

In September 2009, on-line retailer ThinkGeek introduced its own brand of straight slide rules, described as "faithful replica[s]" that were "individually hand tooled".

[51] The Keuffel and Esser Company collection, from the slide rule manufacturer formerly located in Hoboken, New Jersey, was donated to MIT around 2005, substantially expanding existing holdings.