Society of the Song dynasty

Chinese society during the Song dynasty (AD 960–1279) was marked by political and legal reforms, a philosophical revival of Confucianism, and the development of cities beyond administrative purposes into centers of trade, industry, and maritime commerce.

Conversely, shopkeepers, artisans, city guards, entertainers, laborers, and wealthy merchants lived in the county and provincial centers along with the Chinese gentry—a small, elite community of educated scholars and scholar-officials.

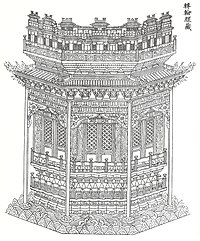

[5] The entertainment quarters of Kaifeng, Hangzhou, and other cities featured amusements including snake charmers, sword swallowers, fortunetellers, acrobats, puppeteers, actors, storytellers, tea houses and restaurants, and brokers offering young women who could serve as hired maids, concubines, singing girls, or prostitutes.

[14] While being served by waiters and ladies who heated up wine for parties, drinking playboys in winehouses would often be approached by common folk called "idlers" (xianhan) who offered to run errands, fetch and send money, and summon singing girls.

[40][41] Following the logic of the Confucian philosophical classics, Song scholar-officials viewed themselves as highly moralistic figures whose responsibility was to keep greedy merchants and power-hungry military men in their place.

Northern Song gentry and officials, who were concerned largely with tackling issues of national interest and not much for local affairs, preferred painting huge landscape scenes where any individuals were but tiny figures immersed within a larger context.

"[57] The entertainment business in the covered bazaars in the marketplace and at the entrances of bridges also provided a lowly means of occupation for storytellers, puppeteers, jugglers, acrobats, tightrope walkers, exhibitors of wild animals, and old soldiers who flaunted their strength by lifting heavy beams, iron weights, and stones for show.

Nonetheless, Song Chinese urban society was teeming with wholesalers, shippers, storage keepers, brokers, traveling salesmen, retail shopkeepers, peddlers, and many other lowly commercial-based vocations.

[79] Not all social and political philosophers in the Song period blamed the examination system as the root of the problem (but merely as a method of recruitment and selection), emphasizing instead the gentry's failure to take responsibility in society as the cultural elite.

[91][92] The Song Imperial examinations conferred successive degrees at the prefectural, provincial, and finally the national (palace exam) level, with only a small fraction of candidates advancing as jinshi, or "presented scholars".

Wealthy families eagerly gathered books for their personal libraries, including the Confucian classics as well as philosophical works, mathematical treatises, pharmaceutical documents, Buddhist sutras, and other genteel literature.

[99] Ebrey states that meritocracy and a greater sense of social mobility were also prevalent in the civil service system: records show that only roughly half of degree holders had a father, or grandfather, or great-grandfather who served as a government official.

[125] In the Southern Song, four semi-autonomous regional command systems were established based on territorial and military units; this influenced the model of detached service secretariats which became the provincial administrations (sheng) of the Yuan (1279–1368), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties.

[126] The administrative control of the Southern Song central government over the empire became increasingly limited to the circuits located in closer proximity to the capital at Hangzhou, while those farther away practiced greater autonomy.

[129] The commissions of Salt and Iron, Funds, and Census that were created to deal with immediate financial crisis after An Lushan's insurrection were the influential basis for this change in career paths that became focused within functionally distinct hierarchies.

[116][130] Lower-grade officials on the county and prefectural levels performed the necessary duties of administration such as collecting taxes, overseeing criminal cases, implementing efforts to fight famine and natural calamity, and occasionally supervising market affairs or public works.

[135] All of these programs received heavy criticism from conservative ministerial peers, who believed his reforms damaged local family wealth which provided the basis for the production of examination candidates, managers, merchants, landlords, and other essential members of society.

[139] Lo asserts that Wang, believing that he was in possession of the dao, followed Yi Zhi and the Duke of Zhou's classic examples in resisting the wishes of selfish or foolish men by ignoring criticism and public opinion.

[140] Yet factional power struggles were not steeped in ideological discourse alone; cliques had formed naturally with shifting alliances of professional elite lineages and efforts to obtain a greater share of available offices for one's immediate and extended kinship over vying competitors.

"[149] Since official promotion was considered by examination degree as well as recommendation to office by a superior, a family that acquired a significant amount of sons-in-law of high rank in the bureaucracy ensured kinship protection and prestigious career options for its members.

A geomancer had to be consulted on where to bury the dead, caterers were hired to furnish the funeral banquet, and there was always the purchase of the coffin, which was burned along with paper images of horses, carriages, and servants in order for them to accompany the deceased into the next life.

[165] Women who belonged to families that sold silk were especially busy, since their duties included coddling the silkworms, feeding them chopped mulberry tree leaves, and keeping them warm to ensure that they would eventually spin their cocoons.

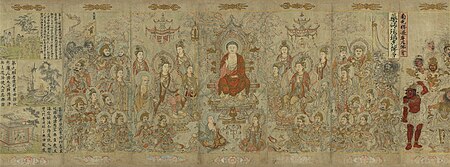

This included the ardent nativist, scholar, and statesman Ouyang Xiu, who called Buddhism a "curse" upon China, an alien tradition that infiltrated the native beliefs of his country while at its weakest during the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–581).

Hong Mai (1123–1202), a prominent member of an official family from Jiangxi, wrote a popular book called The Record of the Listener, which had many anecdotes dealing with the spirit realm and people's supposed interactions with it.

[186]In the Song dynasty, sheriffs were employed to investigate and apprehend suspected criminals, determining from the crime scene and evidence found on the body if the cause of death was disease, old age, an accident, or foul play.

[202] He wrote of examinations of victims' bodies performed in the open amongst official clerks and attendants, a coroner's assistant (or midwife in the case of women),[203] actual accused suspect of the crime and relatives of the deceased, with the results of the autopsy called out loud to the group and noted in the inquest report.

[204] Song Ci wrote: In all doubtful and difficult inquests, as well as when influential families are involved in the dispute, [the deputed official] must select reliable and experienced coroner’s assistants and Recorders of good character who are circumspect and self-possessed to accompany him.

[205]Song Ci also shared his opinion that having the accused suspect of the murder present at the autopsy of his victim, in close proximity to the grieving relatives of the deceased, was a very powerful psychological tool for the authorities to gain confessions.

[213] In 1131, the Chinese writer Zhang Yi noted the importance of employing a navy to fight the Jin, writing that China had to regard the sea and the river as her Great Wall, and use warships as its greatest watchtowers.

[220][221][222][223][224] Song Chinese trade ships traveled to ports in Japan, Champa in southern Vietnam, Srivijaya in Maritime Southeast Asia, Bengal and South India, and the coasts of East Africa.